CD in jewel case

Photography & Design: Jon Wozencroft

TouchShop exclusive – this CD is released elsewhere on 20th September 2010

Mastered by Denis Blackham

The cover shows Mirosław Bałka’s installation at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, “How It Is”, April 2010.

Plus bonus 320kbps .mp3 download – 1 track – 30:59

TO:81DL – Philip Jeck “Live at Corsica Studios”, recorded on 1st July 2010.

This performance was recorded straight to digital from the main desk.

Track listing:

1. Pilot/Dark Blue Night 8:47

2. Ark 4:21

3. Twentyninth 2:36

4. Dark Rehearsal 7:36

5. Thirtieth/Pilot Reprise 2:56

6. The All of Water 8:29

7. The Pilot (Among Our Shoals) 4:33

coda:

8. All That’s Allowed (Released) 3:24

9. Chime, Chime (Re-rung) 7:34

Philip Jeck works with old records and record players salvaged from junk shops turning them to his own purposes. He really does play them as musical instruments, creating an intensely personal language that evolves with each added part of a record. Philip Jeck makes genuinely moving and transfixing music, where we hear the art not the gimmick.

Philip Jeck writes: “A version of “An Ark For The Listener” was first performed at Kings Place London on 24/02/2010. It is a meditation on verse 33 of “The Wreck of the Deutschland”, Gerard Manley Hopkins poem about the drowning on December 7th 1875 of five Franciscan nuns exiled from Germany. This CD version was recorded at home in Liverpool and used extracts from live performances over the last 12 months. The “coda:” tracks are remixes of 2 pieces from “Suite: Live in Liverpool”. “Chime, Chime (Re-rung)” was originally made for Musicworks magazine (#104, Summer 09) and “All That’s Allowed (Released)” is previously unreleased. All tracks were made using Fidelity record-players, Casio SK1 keyboards, Sony mini-disc recorders, Behringer mixers, Ibanez bass guitar, Boss delay pedal and Zoom bass effects pedal.”

An Ark… is Jeck’s 6th solo album for touch since ‘Loopholes’ in 1995. The Wire reckoned it was ‘Stoke’ (Touch, 2002) which ‘made him great, but his body of work and his achingly brilliant live sets are rapidly defining him as one of our best artists, and his recent award from The Paul Hamlyn Foundation confirms him as such.

Philip Jeck studied visual art at Dartington College of Arts. He started working with record players and electronics in the early ’80’s and has made soundtracks and toured with many dance and theatre companies as we as well as his solo concert work. His best known work “Vinyl Requiem” (with Lol Sargent): a performance for 180 ’50’s/’60’s record players won Time Out Performance Award for 1993. He has also over the last few years returned to visual art making installations using from 6 to 80 record players including “Off The Record” for Sonic Boom at The Hayward Gallery, London [2000). In 2010 he won one of The Paul Hamlyn Foundation Awards for Composition.

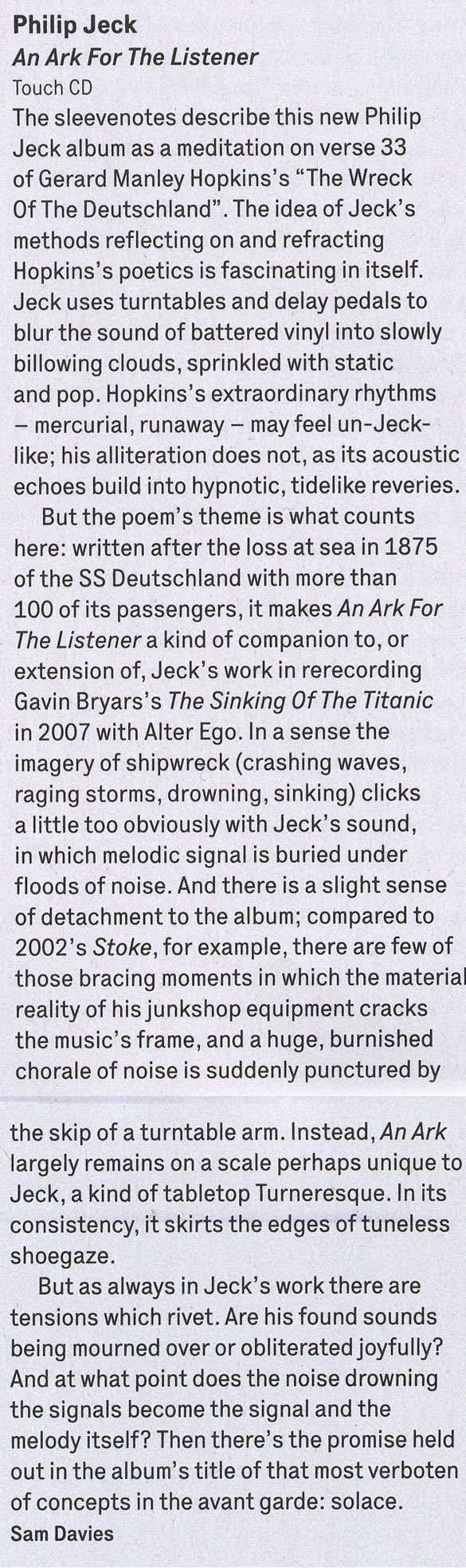

Reviews:

The Sound Projector (UK):

Philip Jeck‘s An Ark for the Listener (TOUCH TO:81) has been with us since 2010. Jeck has long been recognised as an innovator with turntables and old vinyl, and when I spoke to him in 2003 he seemed almost nonplussed to be held in the same regard as Christian Marclay. But it could be that the Dansettes and old records have become something of an albatross for Jeck, and this release may represent an attempt to evolve and expand his sound. Record players are here, but so are keyboards, minidisc recorders, a mixing desk, a bass guitar, and effects pedals. In fact at first spin it’s almost impossible to find the old reassuring swishes, crackles and stuck-record loops that have been Jeck’s signature sound for many years. Like Watson above, he’s going for a blending and layering approach that smooths out many of the rough edges, and transforms signals from vinyl into lush mixed chords of ambient music. At first, it seemed a bit too smooth for me, but a patient listen to the whole suite will reveal a tremendous amount of meticulous detail.

He’s doing it in the service of another meditational piece which, like Sand and Suite before it, involves contemplation of death, loss and bereavement in a very personal and heartfelt manner. In this case, it’s about five people drowning in the ocean in one particular verse of The Wreck of The Deutschland, a poem by Gerald Manley Hopkins. The drowning nuns slowly reach an epiphany across seven long tracks and a two-part coda; along the way, the piece immerses us completely in its very fluid soundworld (‘The All of Water’), finds consonances between souls and shoals, and makes aural rhymes between church bells and ship’s bells. In Hopkins’ original poem, the ‘ark for the listener’ which may rescue mankind is a symbol of God’s compassion and mercy. It would not be inappropriate in the context to view the ‘Pilot’, named here on three separate track titles, as God himself, the pilot of the cosmic ship of mankind, and the religious of this work meet their fate stoically and prayerfully. I find resonances with the 2007 version of Gavin Bryars’ The Sinking of the Titanic, another maritime ship-sinking valedictory work of tremendous import, to which Jeck added nostalgic textures with his turntables.

Foxydigitalis (USA):

Famous for his massed turntable multimedia works, composer and choreographer Jeck here turns in a seductive tone poem, moored by creaks, winds and miniature explosions of static, on a nuclear beachscape of grain. “An Ark For The Listener” is by turns richly beautiful and somnolently spare, at once atonal as it is mellifluous – a dynamic perhaps best exemplified by the climax of the first track, “Pilot/Dark Blue Night,” in which, from a mist of aching haze, a Mellotron-esque pad rises dominant like a choir at the close of a ritual. The effect is curiously exhilarating. In a record content to move slowly through its shades, such moments of dynamism are especially striking – almost akin to the awestruck rush (presumably) felt by a traveler in the dark ages when a church spire were glimpsed through the gloom.

Elsewhere, passages wander with little event, not that one may mind; its internal rhythms and narrative pace grow quickly embracing. Always when asked to articulate thoughts on drone/ambient music, I struggled to spew forth such time-worn adjectives as ‘ethereal’, ‘haunting’ and ‘elegiac’ – such over-ripe observances it would be like describing Paul McCartney’s latter-day Beatles songs as “melodic.” Absolutely, this record IS ethereal, haunting and elegiac, yet when discussing music within which there is so little extracurricular data it seems we as critics must fine-tune our microscopes and look deeper into textures divorced from other critical filters. Here, Jeck has crafted a mesmeric shower of granulated “choirs,” non-geometric forms rising from the mire, ghosts and shadows surfacing for air, before sink into a new miasma. In truth, I cannot discern the sound-sources of any of these pieces – rather than being alienating, it prompts a pure response from the listener – enforcing a disassociation from cornball hallmarks and easy graspings. It sounds fresh and always will, because of this inimitable alien newness. Where a synth pad can be traced directly to a particular module, a certain disappointment can creep (aside from the flagrant but surprisingly forgiveable use of the Yamaha CS1X on Robert Wyatt’s troubling and beautiful “Cuckooland”), a risk elegantly sidestepped by Jeck on this release. “An Ark For The Listener” sounds as though it were beamed fully-formed from signals gathered by the International Space Station, and thus has the rare capacity to propel the listener into an unfamiliar dimension, albeit one steeped in warmth and clarity.

This is a compelling record indeed and one which I would love to perhaps see performed live over a screening of Blade Runner; such is its dystopian ambience. In “An Ark For The Listener,” Philip Jeck has birthed a creaking, otherwordly triumph. [Nick Hudson]

Sakistoreblog (USA):

I can’t recommend Philip Jeck’s new CD on Touch highly enough; it’s a sterling example of his craft, and quite why he’s not as well-known as some of his contemporaries (Fennesz, Tim Hecker) is baffling to me. “An Ark For The Listener” is Jeck’s 1st full-length since the masterful “Sand” (which ended up in The Wire magazine’s top ten for that year) and this is just as nuanced and beautifully executed as that particular release; listening to it, it’s hard to believe the vast spectrum of sounds contained within came from a relatively primitive setup of turntables, minidisc players, and effects pedals. More info available at www.philipjeck.com. Now available at saki!!!

Brainwashed (USA):

On his sixth solo album for Touch, Jeck continues his perfection of using the record player as an instrument (not as a DJ) to create a long-form piece that has no sense of gimmick or cliché, but instead is a hazy, but warm and inviting piece of captivating music that is unlike the work of anyone else. Originally intended for live performance, this studio reconstruction is amazing on its own.

Having never seen performances nor read intimate details of his compositional technique, I’m fascinated by exactly how Jeck coaxes the sounds he does out of his rudimentary instrumentation. On this album, the requisite record players were used, along with the infamous Casio SK1 keyboard, mini-disc recorders, and a bass guitar with only a few effects. How this becomes the gauzy atmospheric music that is presented here, I don’t know, and I think I’ll be happy not knowing as long as the music keeps coming.

A recurring motif throughout the seven “main” songs here is a lo-fi melodic undercurrent that is absolutely immersed in reverb, giving a feeling that’s not unlike the Cocteau Twins or My Bloody Valentine but without sounding like either one of them. In these massive and heavy, but warm waves of sound, occasionally a bit of music is allowed to pass through. Percussion is hinted at on “Pilot/Dark Blue Night” but never fully appears until the closing “The Pilot (Among Our Shoals)” where it takes the form of snappy snare drum loops, with what resembles time-stretched harp plucks and violin notes as accompaniment.

As aforementioned, sometimes the musical source material shines through to the surface, such as on “Twentyninth,” where the big reverberated sounds and cascading guitar tones could be a careful study and dissection of 1980s hair metal, reduced to its most base elements and rebuilt into something entirely different and far more compelling. “Thirtieth/Pilot Reprise” continues this, focusing on hidden melodies and Jeck’s overdriven bass guitar playing with a guitar-like squall and a thin, brittle closing section.

Other pieces are less discernable, such as the dramatic swells of indecipherable sound of “Dark Rehearsal,” which are preceded by some subtle, delicate melodies. “Pilot Reprise/The All of Water” is a chaotic pastiche of layered sound, immediately surging heavily and then continuing on with the same intensity, the sharp waves of sound battle one another over the dramatically drifting undercurrent.

For the album’s coda, two remixes of tracks from Suite: Live in Liverpool are included, sounding noticeably different than the preceding album, but just as strong on their own. Mostly eschewing the hazy ambience of the other tracks, “All That’s Allowed (Remix)” shapes shimmering passages of crystal sound into swirling melodies, keeping a very clean, sharp feel over a dynamic undercurrent. “Chime, Chime (Re-Rung)” focuses on beautifully tactile static bursts covering a bell ringing alongside twinkling wind chimes with the occasional bit of squealing feedback. There is a different sort of audio grime that appears, and the whole song is more loop/sample focused than the other ones, which felt like they had more of an organic drift to them.

Philip Jeck’s work continues to sound like no one else’s, in the best possible way. Regardless of the instruments used, he constructs beautiful, tactile sound that spreads out and engulfs its surroundings, demanding full attention. Few albums I have heard this year are as immersive and captivating as this one. [Creaig Dunton]

Dusted (USA):

The basic process and materials haven’t changed for An Ark for the Listener, the new album by British turntablist Philip Jeck, his sixth solo album for Touch. Using old portable turntables, salvaged records, guitar pedals and a mixer, Jeck makes soundscapes out of surface noise and twists disembodied sounds into ephemeral melodic phrases. Sonically, Jeck’s music compares to the processing-heavy approach of Fennesz and Tim Hecker; all three bounce analog source material between circuits until only spectral sounds remain. Songs and whole albums crystallize around these blurry moans and digital fragments as the artists find structure in distressed signals. On their most recent releases, Fennesz and Hecker deploy sounds that are very similar to the ones that characterized their most popular albums (2001’s Endless Summer and 2006’s Harmony in Ultraviolet) with a greater sense of restraint and dynamics. Like his peers, Jeck has fully established his language by this point and chooses to move forward by dialing back the density. With An Ark, Mr. Jeck is also broadening his narrative scope (the album is allegedly a meditation on verse 33 of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem “The Wreck of the Deutschland”), and the result is a lyrical, superbly paced piece of music.

All this means that Ark has a fair amount of downtime where not much is happening apart from atmosphere. Although this is not unusual for the artist, it makes for a different listening experience than his previous full-length, Sand, which emphasized individual tracks and rough sounds more than the overall album experience. Maybe this brainy calm is a product of the Hopkins theme? Jeck meditates on the stanza, from a poem addressing a shipwreck that took down some nuns, in the same way the late German novelist W.G. Sebald meditates on a dingy English seascape or a murky photo. The thread connecting Hopkins, Sebald and Jeck is memory. And An Ark for the Listener reminds us that remembering always leads to digression. With technology doing so much of the remembering for us (Sebald and Jeck both “play” records; the first uses paper and celluloid ones while the second uses vinyl), the emotional connections between these objects are what matter. By using old, faceless records as his source material, Jeck isn’t quoting, appropriating or alluding. These artifacts are used to set the machinery of memory in motion, and the tone is necessarily melancholic and mournful. It’s intensely subjective and opaque, too, but I’d only call it ambient in a pinch.

Of the artists mentioned above, Jeck is probably the least accessible, and An Ark for the Listener can be a difficult album to absorb. But, in the company of Fennesz’s Black Sea and Hecker’s An Imaginary Country, the album under review seems like it has the greatest chance of outliving the creative crisis that spawned it. Its emotional cues are more subtle. Even at its most inert, it creates a thoughtful environment rather than making the listener uneasy or restless. And every trip through it takes on a different shape. These are pretty basic criteria for the kind of art music Jeck and Co. make, and this style is gaining traction in other venues thanks to people like Oneohtrix Point Never. Sometimes I think this is what all classical music should sound like or aspire to in some secret way.

Jeck’s music remains textural rather than tonal, but he enters into a more musical relationship with his noises on An Ark for the Listener. This may seem like a backhanded compliment, but with this album, Jeck continues an artistic development that’s slower, more deliberate and thoughtful than many contemporary musicians allow themselves. It promises to age well. [Brandon Bussolini]

Aquarius Records (USA):

Of all the sound manipulators, soundscapers and dronologists out there, few can touch Philip Jeck. A master ‘turntablist’, able to create whole new worlds out of sound, to transport the listener to another place, real or imaginary, with just a clutch of record players, a handful of dusty old vinyl, some cheap Casio keyboards, a couple minidisc recorders, a few mixers, a bass guitar and some effects pedals, the musical equivalent of some mad scientist, creating a time machine, or some temporal shift manipulator, out of odds and ends from the kitchen or the garage. The magic is in the process as much as the result, that result being at least partially beholden to the process, not to discount the sheer creativity and ingenuity of the artist. Because that’s exactly what Jeck is, an artist, painting impressionistic landscapes with sound. Instead of colors, he deftly manipulates textures and rhythms, layers and melody, subtly mixing various elements to create something other, the various constituent parts irrelevant to the final piece, like staring at a painting up close, it’s not until you step back, that the various elements coalesce into something magical, and beautiful.

An Ark For The Listener is a sonic mediation on a poem about the drowning of five exile nuns in the 1800’s, and was performed in various locations throughout 2010, this recorded version incorporates bits of the live performances into the final recorded piece, a gorgeously somber soundscape of deep drones and of mysterious sonic swells, the opener “Pilot/Dark Blue Night”, is a hushed drift of stretched out tones and muted sonic garble, a chorus of croaking frogs beneath moaning low end melodies, a slowly unfurling minor key drama wreathed in hiss, truncated rhythms, and clouds of click and chitter, deep bell like tones, and swirling soft focus ambience, culminating in the final few minutes with a super emotional bit of looped strings and epic almost choral swells, strangely skipping, uncharacteristically revealing their vinyl source, but it’s precisely what makes it so intense and mysterious.

“Ark” is a tinkling driftscape of chiming tones, and distant melodies which gradually transforms into a weird bit of droney wah wah-ed bass flutter, “Twentyninth” is a perfect slab of Jeckian dreamdrift haze, shot through with moving minor key melodies, and cinematic like tension, a few of the tracks grow dense and turbulent, the sounds thickening, becoming almost caustic and corrosive, while others seems to grow more and more fragile, diaphanous stretches of crystalline shimmer, the record proper finishing off with the surprisingly rhythmic “The Pilot (Among Our Shoals)”, with its soft avalanche of looped beats, its tangled flurries of pizzicato strings, a soft focus frenzy of dizzing turntable swirl, which gives way to a lovely outro of hushed barely there drift and breathless low end murmur.

The cd tacks on two bonus tracks, reworked versions from the Suite: Live In Liverpool record, one previously released, the other unreleased, both working surprisingly well with the record proper, “All That’s Allowed (Released)” a shimmering expanse of blurred strings and disembodied melody, of softly staticky crackle, and hazy hushed drift, and “Chime, Chime (Rerung)”, a crunchy and tactile stretch of tolling bells, reverberating metal, booming gongs and tinkling chimes, all wrapped in a gauze of crackle and pop, buzz and warble, the whole thing lit with some glimmering shimmering otherworldly light. So great.

The Wire (UK):

KindaMuzik (Netherlands):

Philip Jeck is een Brits geluidskunstenaar die er een heel eigen stijl op nahoudt. Hij wordt immers niet voor niets door Godspeed You! Black Emperor als gast gevraagd voor de door hen gecureerde editie van het All Tomorrow’s Parties-festival op het einde van dit jaar. In de regel gebruikt hij oude platen en oude platenspelers om geluiden te creëren die hij dan tot organische ambientachtige stukken herwerkt. Voor An Ark for the Listener geldt dit ook, al houdt Jeck zich eveneens ledig met keyboards, minidiskrecorders, mixers, delay- en effectenpedalen en een basgitaar.

Jeck put zijn inspiratie uit een negentiende-eeuws gedicht van Gerard Manley Hopkins. Op An Ark for the Listener mediteert Jeck over The Wreck of the Deutschland en dit resulteert in organische soundscapes met titels als ‘Dark Rehearsal’ en ‘The All of Water’. Het gedicht gaat over de verdrinkingsdood van vijf uit Duitsland verbannen franciscaner nonnen.

Wat de context en Jecks opnamemethodiek ook is, An Ark for the Listener hoort perfect thuis op het label Touch, dat zich al jaren specialiseert in intrigerende soundscapes en niet-alledaagse geluidsexperimenten. Op basis van dit werkstuk is Jeck een uitgesproken exponent van deze muzikale beweging die de kunst verstaat om geluiden zodanig te analyseren, vervormen en samen te stellen dat er een organisch, spannend en gevarieerd eindresultaat tevoorschijn komt.

Het album sluit af met twee remixen die onder de subtitel Coda geklasseerd worden, beduidend minimalistischer maar getuigend van eenzelfde finesse. [Hans van der Linden]

Armchair Dancefloor (UK):

Philip Jeck’s new album, ‘a meditation on verse 33 of The Wreck of the Deutschland’ by Gerard Manley Hopkins, was made with old vinyl played on rickety turntables, delay pedals, keyboards, minidisc players and a bass guitar with an effects pedal. Those familiar with Jeck’s work, which he has been producing since the early 1980s, and releasing in album and other formats since the mid-1990s, will probably appreciate his ability to manipulate unconventional raw material into compelling sounds that, no matter how grand in scope they become, always have something of the frayed edge or unstable, tattered centre about them. Here, it seems irresistible to think not of the sinking of the Deutschland as it happened in December 1875, but of a wreck that’s sunk for decades in the water, rusting and rotting, and becoming overgrown with barnacles and seaweed. One distinctive pattern repeats throughout, a signal that flares and recedes like a sonar sweep. There is a tension at work throughout the piece, but also, in the powerful ‘The All of Water’, a distinct feeling of comfort and consolation. [Chris Power]

Rockerilla (Italy):

Ondarock (Italy):

Immagini nebbiose, cortine oscure, gocce evanescenti e impercettibili possono ritrovarsi in migliaia di lavori. Ma è nelle sfumature che si coglie la sostanza, l’humus fertile capace di rendere un flusso semplice accozzaglia o pura estasi. Il bandolo della matassa Philip Jeck l’ha trovato spesso, sbagliando raramente bersaglio. E l’attesa conferma della solidità delle sue creature non viene affatto scalfita dalle nuove tracce di “An Ark For The Listener”.

Pennello alla mano, la tavolozza propone tinte cupe, gelide e ovattate nel loro dipanarsi. A tenere le redini, un Jeck in stato di grazia, che modula con estrema perizia il basso, i suoi record-players, la fida tastiera Casio. A emergere sono una cinquantina di minuti di pure strutture dark-ambient che flirtano con drone catacombali. Quando i toni si fanno via via più tetri, tornano alla mente i Troum più cupi e dilatati.

I fantasmi di Kevin Drumm o di Yen Pox aleggiano in maniera persistente, affievolendosi talvolta in rivoli folk-finnici o tribalismi assortiti (“The Pilot (Among Our Shoals)”). Pur non mancando inteludi quieti (il gelido carillion in dissolvenza della seconda traccia), l’architrave portante del lavoro è costituita dalle maestose discese ombrose di “Pilot/Dark Blue Night”, dalla fiamma celeste in quota Tim Hecker di “Twentyninth” e dall’acciaieria subacquea “Dark Rehearsal”, per non parlare della fluidità materica di “The All Of Water”.

Non c’è nota fuori posto o incertezza alcuna in “An Ark For The Listener”. Una bellissima conferma, sempre che ce ne fosse bisogno. [Alberto Asquini]

Blow Up (Italy):

Mapsadaisical (UK):

The SS Deutschland set off from Bremerhaven, Germany, on 4 December 1875. Headed for New York via Southampton, it ran aground in a blizzard on the Kentish Knock, a shoal situated about 30 miles east of the Thames estuary. 78 of its passengers died when the ship broke up in the storm, including five Franciscan nuns who were fleeing Germany after the passing of the anti-Catholic Falk laws (the graves of four of those can be found in Leytonstone cemetery, only a few miles from the parish in which I currently sit). The English poet Gerard Manley Hopkins (who lived in Hampstead, a couple of miles in the other direction), wrote a poem on the subject almost immediately after its sinking.

Hopkins’s biography is a fascinating one; he converted to Catholicism seemingly as an extreme response to his own homosexual impulses. On conversion he burned all of his previous work, and stopped writing for seven years before he was moved to write The Wreck Of The Deutschland. The poem is famous for its innovations in metre and rhythm, but the content is equally startling. It takes him 12 stanzas to even mention the boat (yes yes, I’ll get to the album soon), never mind the nuns; the entire first part being a celebration of Christian faith. The work is dedicated to “the happy memory of five Francisan nuns”; Hopkins’ faith meaning that the drowning of the nuns is in some way as much to be celebrated as the survival of so many others (actually, their fates are deemed barely worthy of a mention). So here we have an innovative work with themes of religion, death, rebirth, joy, sorrow, and, of course, water. Enter Philip Jeck.

Jeck’s new album an Ark For The Listener is a response to Hopkins’s poem, its title being derived from stanza 33 (“With a mercy that outrides/The all of water, an ark/For the listener; for the lingerer with a love glides/Lower than death and the dark”). That Jeck has produced a work based on a poem is nothing new; indeed his last studio album, the masterly Sand, was inspired by Emily Dickinson’s The Chariot. That Jeck has produced an album based on this watery subject matter is also not a surprise, his involvement with a new version of Gavin Bryars’s The Sinking Of The Titanic resulted in the definitive reading, creating an emotional archive, memories and artefacts pasted into an aural scrapbook. Jeck’s best work seems to come about when he restricts his scope in some manner, focusing in depth on a subject, or indeed a particular source material (see also the recent set I saw him perform at the North Sea Jazz Festival, when he limited himself to using jazz records). On An Ark For the Listener, the majority of sounds are sourced from recordings of bells.

Bells have been a recurring theme of his work for a number of years now. The track “Chime, Chime”, a version of which appears as a coda on the end of this album (as “Chime, Chime (Rerung)”) was included on his Suite: Live In Liverpool set, recorded in 2006. The extensive use of bells is a simple, yet extremely fulfilling idea. Even without the application of Jeck’s trademark layers of crackle and distortion, bells can evoke feelings of joy and sorrow, ringing out to celebrate a birth, or to mark a passing; most usually, they just denote the passing of time. Of course, by the time that Philip Jeck has finished with them, they end up sounding like a shipwreck. These vinyl-derived sound sources are supplemented by a variety of additional material, from classical music loops to Jeck’s own keyboards and bass guitar, to produce a deep, dark, and incredibly haunting piece of work.

The opening track “Pilot/A Dark Blue Night” is a Jeck classic, one of the richest pieces he has created. It begins with a distant tolling, proceeding at a rapid rate of knots to ominous drones, voices whispering in the hold. Harsh vinyl loops toss the piece in the wind, before there is a moment of calm, and of near-joy: a swoon of a heart, a rush of strings, some classical music building. Intriguingly (and in somewhat Catholic fashion), Jeck denies us the climax, skipping round the crescendo and re-emerging on the gentle downslope. I’ve already said that this is a haunting record, but nothing haunts me more than that missing section; in that sudden slice, a whole other world is excised, whole lives even. It is a jump-cut Godard would be proud of. It gets darker from then on; by “Twentyninth” the bells are ringing in alarm, and on “Dark Rehearsal” the sound mix is beyond rescue, the flood of the wave filling the space. The shattering “The All Of Water” takes it all down, lashing it, gnashing on it, and submerging it, ringing bells and elegiac melodies fighting for breath amongst an oceanic groan. The death and the dark, right there, on that shoal.

Most of the album thus far was recorded at a concert in Kings Place in February, 2010. It doesn’t finish there though. There is a two song coda on the end, one which, despite all that has gone before, seems to hint at the possibility of redemption. The aforementioned “Chime, Chime (Rerung)” twinkles, wafting through starlight, gentle metallic ripple standing in stark contrast to the anvil-ding of the album’s opening. In context, it makes perfect sense. And context is so important with this record. It is one thing to hear this record, but another to really listen to it, to reach down through the patina of crackle to what Jeck is trying to achieve. The title, An Ark For The Listener isn’t just a reference to the poem, although I’d like to think that Gerard Manley Hopkins would hear a kindred innovator in these grooves.

If you buy it from the Touch Shop, you get a free download of an excellent Philip Jeck set from Corsica Studios.

Freistil (Germany):

Le son du Grisli (France):

C’est en s’inspirant d’un poème de Gerard Manley Hopkins et en réutilisant des enregistrements de ses concerts que Philip Jeck a accouché d’An Ark for the Listener. Le disque a été fait à la maison et c’est peut-être pour cela qu’on y trouve des choses familières à Jeck et que nous avons maintenant en commun avec lui.

Dans l’atmosphère par exemple il y a des drones qui jouissent d’un espace réverbéré hors du commun mais il y a aussi des carillons naïfs. Dans l’atmosphère pour prendre un autre exemple il y a d’énormes basses et des loops tonitruantes mais il y a aussi une propension du grand tout à verser dans une pop gentillette. D’un titre à l’autre, on passe d’une musique dérangée à une musique dérangeante, selon que Jeck préfère le son à la mélodie ou la mélodie au son. Ce qui est dommage, c’est qu’on sait qu’il peut mieux faire.

Pitchfork (USA):

It’s been interesting to hear new records this year from a number of turn-of-the-millennium experimentally minded artists: The past couple of months have brought releases from Oval, Fennesz (working with guitarist David Daniell and drummer Tony Buck), and now the turntable collagist Philip Jeck. Music from this sphere tends to move pretty fast, but in the case of these three, they’ve mostly stuck with variations on their distinctive, well-honed sound. For Jeck, that sound is built from old vinyl. His training is as a visual artist, and his primary medium is his live show that sometimes touches on installation art. Using a few turntables, a keyboard, and pedals, Jeck expertly mixes, loops, and layers passages from old records and molds them into an instantly identifiable aesthetic. At his best, he makes some of the most moving and replayable experimental music around.

There are ideas running through Jeck’s music that have been at the forefront of conversations in the last couple of years. He digs up cultural artifacts from the past (in his case, vinyl) and recontextualizes them, so his music touches on nostalgia and memory and the passage of time, and it invites you to meditate on the way that cultural information disappears and reappears and what that might mean. But where younger artists are applying these ideas to the music of their childhood and turning over signifiers of the 1980s and 90s, Jeck takes a longer view. He’s almost 60 years old, and for him, the entire history of recorded sound is fair game. Couple this with his high-art background, where he’s much more likely to play an auditorium or art gallery than a club, and it makes sense that Jeck’s music has a symphonic character. His records feel more like classical music, and, unlike so much turntable-based music since the rise of hip-hop in the late 1970s, they have no overt connection to pop. Jeck’s music seems designed for a big room where people want a certain kind of overpowering experience, and he knows how to deliver for this audience.

An Ark for the Listener is Jeck’s first widely available solo album since 2008’s Sand (he had a vinyl-only live album in between, along with a couple of other small-scale releases). Where Sand was built around a central idea– it was a concept album that riffed on the notion of the “fanfare”– and had a unified sound, An Ark for the Listener is held together more loosely. The music here was developed in live performance and was based around a stanza from an epic Gerard Manley Hopkins poem about a maritime disaster, “The Wreck of the Deutschland”, but there aren’t obvious connections between that source and the music at hand. Ark comes over more like a survey of some of the things Jeck does best.

I will say that the Hopkins poem that inspired the project explores death, and Ark is an especially dark LP that is particularly heavy on drone, as Jeck loops and layers dissonant passages of strings into tense and uneasy held tones. “The All of Water” is especially stirring in this vein, with a richness in texture reminiscent of the spiky drones of Tim Hecker, even though the sources here sound like old classical recordings. The following “The Pilot (Among Our Shoals)”, which builds on that template and adds a drum roll and indistinct screeching tones that echo and flange wildly, is the sort of track that virtually no one else could have pulled off. It feels like a scratchy black and white film with bits of music from all over fluttering into the frame, and somehow manages to reach back 100 years while sounding utterly contemporary. And then “Ark” finds Jeck experimenting with a greater amount of space, as he opens with a long passage of creepy bell tones that sound like a ghostly music box from another realm. Each track here has its own character and establishes its own context, and Jeck’s finely-tuned ear manages to bind them together. And if An Ark for the Listener may not be the best place to start for the curious (Stoke or 7, both of which add more lyricism to the mix, are better in that regard), it finds him working at a characteristically high level, which is very welcome indeed. [Mark Richardson]

Other Music (USA):

Multimedia composer Philip Jeck has thus far carved an impressive career out of the willfully archaic. Though nominally a “turntablist” (pretty much only in the respect that he favors record players as part of his set-up), Jeck’s unremittingly brilliant solo records have again and again found the man breathing life anew into dusty, weathered slabs of vinyl. Concerned not with the beatscape or the clever juxtaposition, Jeck’s hands display a remarkable sleight in their ability to deal with subtlety — appropriated melodies, implied memories, and genteel processing that treats source material with the utmost respect while folding it seamlessly into new compositions.

Given the singular dedication to his particular brand of ambient craft, it’s no surprise that An Ark for the Listener, Jeck’s latest for the Touch label, is of a piece with much of his other work (and his contributions to collaborative works with the likes of Jacob Kierkegaard and Gavin Bryars) — which is not to suggest any stagnant tendencies on Jeck’s part, but rather a steady refinement of craft that allows for new depth with each outing. Reviving a live piece based on a Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem that dealt with the drowning of five nuns exiled from Germany, Ark focuses on gradual development, with faint melodies subsumed by the depths of Jeck’s tones, effectively conveying the steadily diminishing hope and creeping dread suggested by the subject matter. Haunting and affecting all throughout, this latest piece from Philip Jeck is not only essential for tried and true fans, but for those who’ve worn out their stash of material from the likes of Stephan Mathieu, William Basinski, or even Christian Fennesz (on a particularly experimental and pensive day). [MC]

Tinymixtapes (USA):

Philip Jeck’s latest album for Touch follows faithfully in the path of previous work by the British artist. As before, Jeck mixes the sound of salvaged Fidelity record players with Casio keyboards, minidisc recorders, bass guitar, and effects pedals. The use of old turntables as instruments serves to highlight the bygone sounds of machines once considered the height of sonic fidelity and convenience. Jeck is not being true to the original function of this technology, but rather to its subsequent history as a way of mediating time and space.

Jeck’s work shows fidelity to hip-hop aesthetics in ways that go beyond the obvious connections of turntablism and sampling. Most notable, perhaps, is the way his art engages with questions of space, at one moment seeming to faithfully reflect an external sonic world, the next engaged in creating sonic space itself, summoning up seemingly tangible sites in which to place its listeners. Hip-hop followed a trajectory that began with the sonic reappropriation of urban space, then, via producers such as The Bomb Squad, the production of an aural reflection of urban noise, before going on to claim the mainstream soundscapes of shopping centers and the mass-mediated spaces of popular culture. From the subcultural confines of pedestrian-based locales to the booming ubiquity of jeep beats, hip-hop steadily territorialized sonic space as the millennium approached.

What was left behind is hinted at in alternative hip-hop, grime, and dubstep’s haunted ghost samples. Jeck’s work taps into this refuse and can even be seen in hindsight as a kind of proto-dubstep, its technological crackles and blurrings hinting at a subterranean soundworld at once contemporaneous and hopelessly lost. It is highly appropriate that Jeck uses old vinyl records and discontinued turntables as the mainstays of his art, for the sonic textures they provide serve as reminders of the spectral persistence of supposedly obsolete technologies. But if vinyl has refused to go away, its cultural memory work is hardly a mainstream pursuit, meaning that its fetishists labor in a kind of constant limbo between present and past.

This subterranean aspect seems particularly relevant to An Ark for the Listener, which was inspired by a Gerald Manley Hopkins poem written as an elegy for five nuns drowned at sea in 1875. The work is divided into seven discrete pieces, each bearing its own title. As in other shipwreck-inspired works — Gavin Bryar’s The Sinking of the Titanic, Denis Eberhard’s Shadow of the Swan, or Explosions in the Sky’s “Six Days at the Bottom of the Ocean” (the latter two both inspired by the Russian submarine Kursk) — the soundworld evoked is an underwater one that alternates between hypnotic fascination, isolation, and terror.

There’s an icy clarity to second track “Ark,” which manages to mix a sense of calm with an equal sense of foreboding. It’s hard to know whether we are above or below the water at this point. “Twentyninth,” like Eberhard’s work, is built on descent, while sounds of dripping water presage imminent disaster as they echo uncannily through the metallic corridors of “Dark Rehearsal.” “The All of Water,” the penultimate track of the suite, delivers the most terrifying message, its wall of noise rising in crescendo to first envelop, then crush the listener in its ocean of sound.

Woven around these pieces are three iterations on a piece entitled “Pilot,” the last of which is most reminiscent of Jeck’s earlier work. Temporarily eschewing the sparse, becalmed sonics of the preceding tracks, “The Pilot (Among Our Shoals)” manages a stuttering beat that hints at some sort of rebirth, only to fade again into the silence of the lost.

There are two “coda tracks,” remixed from the vinyl-only 2008 album Suite: Live in Liverpool. Both fit with the muted, elegiac mode of Ark, especially “Chime Chime (Re-rung),” with its vinyl crackle suggesting the ways in which loss is as much about transference as absence, about the creation of new sonic textures via the obliteration of old. What has gone leaves in its wake a new sonority; in Jeck’s hands, records and record players act as mediums to channel those ambient ghost sounds. An Ark for the Listener provides a suitably spooky séance and helps to cement Jeck’s reputation as an unparalleled purveyor of phonographic memory work.

The Line of Best Fit (UK):

The novelist and poet Gilbert Sorrentino once visited Louis Zukofsky, best known as the author of the monumental epic poem ‘A’. The conversation eventually turned to Zukofsky’s equally-epic study Bottom: On Shakespeare. The aging Modernist asked Sorrentino if he’d like to see his notes for the book. At 470 pages, with a 232 page accompanying volume of music by his wife Celia, Bottom was one of the longest studies of the bard to date. Sorrentino’s astonishment at the opportunity turned to shock when Zukofsky handed him nothing more than a dozen or so index cards filled with his tiny, neat script. Sorrentino asked how this scant collection of notes could have generated such an enormous and complex text. “They were really just suggestive,” Zukofsky drily answered.

Philip Jeck is also a Modernist, but he employs an ancient technique: the patchwork poetic form of the cento. A cento is a composition made up of lines selected from the work of other poets to form a new work. (One of the earliest examples is Trygaeus’ repurposing of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey in Aristophanes’ “Peace”, written in 421 BCE, to form an entirely new work.) It is a method still used today, with notable examples by John Ashbery and Harry Mathews. And it was used by Zukofsky at the opening of “A”-22.

Jeck’s work creates aural centos that merge various recordings and his own instrumentation and processing, placing all of these voices in comparison that reveals contrast, elevating found objects to the realm of art, and from there to the realm of idea. Salvaging old record players and LPs, Jeck takes these mere “suggestive” antecedents and transfigures them into his art. Jeck has made a career of filing his source materials into sonic silos and then feeding them through his fertile imagination and compositional genius. And some inspired choices in electronic gear, of course. The voices of the past aren’t merely left alone. They are funneled through Jeck’s processing and processes–where the ultimate form resonates from within. The multitude of ingredients he employs are washed clean, made new. Hearing the occasional vinyl crackle surge through is a reminder that these are aging voices of the past speaking again through Jeck’s engagements. A composed rebirth.

Jeck wrote that An Ark for the Listener is “a meditation on verse 33 of ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland’, Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem about the drowning on December 7th 1875 of five Franciscan nuns exiled from Germany.” Hopkins, a Roman Catholic convert, Jesuit priest and revolutionary poet, has been hailed as the bridge to the Modernists. His “running” or “sprung” rhythm was the precursor to free verse and broke open rhythmic structure. Hopkins was among the first modern authors to focus on language as a subject-in-itself, and anticipated the major explorations of form found in the 20th Century. Robert Creeley would say around 1950, “Form is never more than an extension of content,” and Jeck shows a poet’s control of each. He shows that in open form there can still be structure and that the process of combination, the creation of the patchwork, makes something new. What Creeley called “a content which cannot be anticipated.”

There’s a spiritual underpinning at work here, as of course there was for Hopkins. Both Jeck and Hopkins are meditating on the tragedy of the shipwreck and the death of the nuns, as well as the transformative power of art. Marvelous that Hopkins phrases these lines “The all of water, an ark / For the listener”: the juxtaposition of the definite and indefinite articles implying a singular “all” and a potential plurality of arks. The reader can board any number of these arks, and the listener can find different colors and nuances upon each exploration of An Ark for the Listener. There is no map to this place, but you have a compass. It will guide you through the ingenious forms of Philip Jeck’s contents. To reach the final realm of idea, the listener must listen. Listen. [Tom Lecky]

The Silent Ballet (USA):

By now, there’s fairly solid evidence that Philip Jeck is a special kind of modern Romantic. He makes music bloom from the fragmented words and sounds of tragic histories and poets, veiling an undercurrent of emotions and faith with waves of noise and sound experiments. This is a faith of transcendence, of an artist that bears the burden of song and its endless possibilities to change one’s life. This hardship-filled work is his soliloquy unraveled and revealed in all its mysterious glory.

The poem upon which this work is based is a grand expression of belief in a God manifested as furious-yet-merciful nature. In the poem, a God “throned behind Death” inexplicably deems it necessary to wreck a ship that hosted five catholic nuns, exiled from Germany in 1875. If the poem is a deep cry of a once-shattered and thousand-times reinforced faith, this album follows a similar line, lamenting the loss of meaningful Western art. Like a religious teaching, it’s there for all to see and hear, operating as “an ark for the listener” that “glides / Lower than death and the dark”.* It will stay with people until the very end, until the water drowns out the last, tenacious notes.

Jeck’s vehicle is made of bells and distorted recordings. The broken introductions found on the first track hurriedly dive into silence, only to surface moments later amidst the croaking electronics of a “Dark Blue Night”. Every sound stays within low registries and seems to drone onward toward quietness, toward a krautrock-like psych soundscape of sorrowful meditation. At times the effect can be disturbing, in ways seldom reached by the ‘dark ambient’ crowd. An Ark weaves tales of swirling natural terrors: the nerve-wracking sound of the sea in all of its chaotic, dissonant grandeur. The muffled mantra of “Dark Rehearsal” is another prime example, droning deep into the ocean to the sense-heightening blackness of the abyss.

The most striking moment arrives at the end, when “The Pilot (Among Our Shoals)” drifts into our ears. The track slowly sails into the certain doom of mammoth drum loops, cut-up bits and raging, crazed string melodies and chords, tearing apart the fabric of what we’ve been listening to so far. And then, after what seems like an instant, the previous tonalities return. All returns to ‘normal’ at the bottom of the sea, in the fading peace of death. The struggle lasts but a minute or so; what we would imagine as endless days of intense suffering and fear is complete and finished in but a minute of drowning. After that, everything else remains, and we realize that the drowning was but a short segment of life on a lengthy time line of demise. The soundtrack of bells and electronic distortions is a perpetual call, one that is interrupted for mere seconds by throes of life and then resumed, calling and calling for those whose time has come. In the coda, we are fittingly left with a million chimes.

Yet for all its amazing sounds and emotional provocations, An Ark for the Listener misses some of the strong, constantly changing sampling that characterized Sand and some of the artist’s other prior works. As dramatic and masterful as “The Pilot (Among Our Shoals)” may be, this album could have also used the severely dramatic impulse of 2008’s Sinking of the Titanic. Listening to An Ark is not immediately rewarding, and while many surprises surface with time and multiple plays, it remains less absorbing than the other works mentioned.

Nevertheless, on this album, Jeck does try to show us the imaginative power of music, creating sounds so emotionally charged they might make us cry and meditate upon our oh so finite nature. He does so with a brilliant sensitivity that seems in tune with the poem that inspired the project. In this sense, the album is a success, and serves as evidence that even the most challenging of works can be emotionally intricate and deeply resonant, touching on time-honored themes such as mystery, nature, and religion. As an experiment, the album is a success, but as music, it is surprisingly even better. [David Murietta]

allmusic.com (USA):

Since the 1980s, Philip Jeck has been creating sound sculptures — some of them quite abstract, others structured with beats and audible progressions — using junk-shop record players, outdated Casio keyboards, basses, effects, and other digital and analog miscellanea. An Ark for the Listener started out as a live performance at Kings Place London in February of 2010; after about a dozen more live performances, Jeck took recordings of them back to his home studio, extracted passages from the recordings, and used those extracts to create a new studio version. The seven-part piece was inspired by a Gerard Manley Hopkins poem about a shipwreck in which five nuns drowned, though the music contains no explicit musical or lyrical referents to it. It opens in a dark and arrhythmic mode with “Pilot/Dark Blue Night,” a track that gradually becomes oddly brighter and more open, incorporating what sound like creepily altered radio samples; “Ark” blends chiming bell tones with glockenspiel sounds, and is aimlessly lovely. “Pilot Reprise” and “The All of Water” sound like afterthoughts, with chords and noise carelessly piled on, but “The Pilot (Among Our Shoals)” is especially interesting: faintly sampled beats combine with almost recognizable melodic fragments to create something that sounds like a remix of a Bill Nelson track circa 1983. The album closes with a couple of remixes, both of them quite pleasant. [Rick Anderson]

Gonzo Circus (Belgium):

Op 7 december 1875 verdronken vijf kloosterzusters die verbannen werden uit Duitsland een roemloze dood. De dichter Gerard Manley Hopkins schreef later het gedicht ‘The Wreck Of The Deutschland’ over het gebeuren. Een deel van het gedicht inspireerde Philip Jeck tot het maken van een nieuwe plaat. De Brit is hiermee niet aan zijn proefstuk toe. ‘An Ark For A Listener’ is zijn zesde plaat op het Touchlabel, daarnaast maakte hij ook soundscores voor theatervoorstellingen en films. Vorige jaar nog leverde hij een erg belangrijke bijdrage aan de heruitvoering (heropname) van ‘The Sinking Of The Titanic’, het meesterwerk van Gavin Bryars. Jeck speelde het voorbije jaar ‘An Ark For A Listener’ verschillende keer live en maakte opnames van deze sessies die hij in zijn homestudio bewerkte en nu als semi-liveplaat uitbrengt. Opvallend aan de plaat zijn de rijke schakeringen, de vele variaties en de diepe klanken (de helft van de tijd lijkt het alsof je onder water aan het meeluisteren bent) waar Jeck al sinds zijn debuut een patent op heeft. Ook nu zijn zijn Dansetteplatenspelers, de minidiscrecorders cruciaal in zijn werkprocédé, maar Jeck gebruikte hier ook een Casio SK1 keyboard, een basgitaar en verschillende effectenpedalen die het werk sterk kleuren. Jeck is een van die zeldzame artiesten die er in slaagt om trouw te blijven aan zijn idealen en er toch in slaagt om met iedere nieuwe plaat zijn eigen grenzen te verkennen en te verleggen. ‘An Ark For A Listener’ is met voorsprong zijn beste werk, een conclusie die we met iedere nieuwe plaat maken. [pds]

Bergenstid (Norway):

Dark Entries (Belgium):

Philip Jeck is met zijn 15jaar dienst voor Touch Music reeds een veteraan. Ondanks zijn lange staat van dienst is hij zichzelf echter blijven vernieuwen, zonder zijn basisbeginselen echter te verloochenen. Zo blijft hij zweren bij zijn basis van oude apparatuur en blijft hij oude platen gebruiken om hier en daar een solide background mee op te bouwen. Daar bovenop gaat hij aan het werk met allerhande akoestische en electronische toestandjes tot hij weer een van zijn hypnotische en organisch aandoenden soundscapes klaar heeft. Op dit album (zijn zesde voor Touch Music in die tijd) toont hij zich weer de zelfzekere maar bescheiden grootmeester in geluid die hij is.

De titel van dit album, ‘An Ark for the Listener’, is een referentie naar het gedicht ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland’ van Gerard M. Hopkins; kennen we niet… en we laten die intelectuele invalshoek los. Interessanter voor ons is te weten dat dit album oorspronkelijk een performance was. Dit maakt het nog geen livealbum, want Jeck nam van verscheidene optredens opnbamen mee naar huis om ze thuis zodanig om te bouwen tot hij tevreden genoeg was. Het resultaat loont de moeite, althans indien u van experimentele avantgarde houdt…! Het leverde hem in ieder geval een Paul Hamyl Foundation Award op… 8/10 [Jan Denolet]

Cyclic Defrost (Australia):

Arch turntable manipulating, junk-shop scouring, sound artist Philip Jeck has developed a signature methodology that has been ably supported by the Touch label since 1995. An Ark for the Listener is Jeck’s sixth full-length release for the label. As always, the design and packaging of this latest Touch release has that instantly recognizable Jon Wozencraft imagery that signifies the considered approach to the finished product that speaks of a label in quiet command of a potent product.

Whilst not as immediately breathtaking to these ears as Stoke, from 2002, whose shuddering and jarring, yet scintillating, layers of found sound coalesced into an awesome audio experience, An Ark for the Listener is the sound of an artist who has allowed his practice to develop into new areas and blossom into captivating, more meditative spaces. I’d pontificate that this new album didn’t captivate me quite as instantly as Stoke, due to the fact that a whole new generation of musicians are now releasing sounds in a similar realm to Jeck. Artists as diverse as Tim Hecker, Oneohtrix Point Never, ‘Hauntology’ and Oren Ambarchi have explored similar sound spheres, possibly influenced by Jeck’s layering and juxtaposition.

Speaking of meditations, the first seven tracks of An Ark for the Listener are a response to verse 33 of Gerard Manley Hopkins epic poem ‘The Wreck of the Deutschland’. Hopkins’ poem takes as its subject matter the 1875 drowning of five exiled Franciscan nuns after leaving Germany, and there is a certain solemn aquatic feel to Jeck’s interpretation, which uses extracts from live performances recorded over the past year.

On ‘Pilot/Dark Blue Night’ the sonorities of industry are washed with unidentified sounds from nefarious regions. The conclusion of the album opener reminds me strongly of the feel of Tim Hecker’s ‘Haunt me, haunt meŠdo it again’; a delayed echoic majesty is slowly sabotaged by Jeck’s eroded phonographs. ‘Dark Rehearsal’s’ ambience is more of the Coil variety, blackened, melancholic and decidedly off-key. A processed, rubbery bassline slowly asserts itself, offering a welcome diversion from the industrial-tinged hues.

‘The All of Water’ feels like the centrepiece of Jeck’s meditation on ‘Deutschland’; a massive, roomy echo swells into aquatic ambience, all deep layers of organic sounds. ‘The Pilot (among our Shoals)’ is reprised for the third time, delineating the pieces that Jeck has performed over the last year from the two remaining on the album. This time, ‘The Pilot’ sounds much more recognisably Jeck-like, looped drumming and glitched symphonic strings that start to pile up on each other.

The coda of ‘All That’s Allowed’ and ‘Chime, chime (re-rung)’ bring to mind half-dreamt memories of lunar landings, 1001 strings, and the warm breeze of a summer day in equal measure. An Ark for the Listener gradually asserts itself as an album by none other than Philip Jeck, whereupon I retreat to my vinyl and await his next imagining with baited breath. [Oliver Laing]

Hair Entertainment (Germany):

Meditative, cerebral, brooding, with An Ark for the Listener Philip Jeck returns to the theme of a shipwreck, this time filtered through the poetry of the visionary poet Gerald Manley Hopkins. Jeck states that verse 33 of ‘The Wreck of The Deutschland’ a poem ‘about the drowning on December 7th 1875 of five Franciscan nuns exiled from Germany’ the as his specific model and Hopkin’s words frame the music more fittingly than anything this writer can concoct. As each successive track washes over the listener, it is apparent that the themes of terror and transcendence embedded in ‘The Wreck of the Deutchland’ are carried through into Jeck’s music, this is a work carrying powerful emotions. The spectral bells of the second track ‘Ark’ manage the enviable trick of attaining an awesome level of solemnity and creepiness without drifting into camp or kitsch. The horn like swells in ‘Twentyninth’ and ‘Dark Rehearsal’ evoke a steam ship and hint at destruction with a heart-breaking gentleness. The church organ-like chords of ‘The All Of Water’ are underpinned by buzzing that hints at machinery moving below the surface. By the time beats emerge along with frantic harp and fiddle playing, the experience is sudden and disorientating. The comparison of sound, with its ability to envelope the body, even induce feelings of suffocation, with water is not a new one, but in An Ark for The Listener, Jeck has produced a particularly powerful embodiment of this analogy. Unashamedly metaphysical, grandiose and serious, this music manages to capture something of the calm of deep ocean, the primal chaos of the storm and contradictory bliss some attain though religious faith. [Nick Ilott]

Sonic Seducer (Germany):

Exclaim (Canada):

Though his use of junkshop turntable and vinyl has always been idiosyncratic, Philip Jeck’s sixth solo album for the Touch label pushes even further past the sample and crackle expectations of the source material. Taking a verse from the Gerard Manley poem “The Wreck of the Deutschland” as inspiration, Jeck builds an appropriately aquatic atmosphere to describe the drowning of five exiled Franciscan nuns. Tracks like “The All of Water” combine the slow, nearly static pulse of a drone to express the vast directionless expanse, with the constantly shifting, overlapping coloured tones providing power and kinetic energy. There are passages in “Ark” and “All That’s Allowed” where Jeck’s sonic wash becomes still enough to hear bells and other sounds that tease with hopes of rescue and melody. Ark works as a requiem, not unlike Gavin Bryars’ The Sinking of the Titanic, with melancholy that isn’t recollected in minor chords, but present in the aural approximation of being lost at sea. [Eric Hill]

Culturmag (Germany):

Minidisc, anyone?

Das Ende des Vinylzeitalters ist ja schon längst selbst an sein Ende gekommen, und man braucht keine prophetischen Fähigkeiten um zu sehen, dass uns das ewige Downloaden, Synchronisieren und Updaten unserer multiplen digitalen Geräte bald dermaßen auf den Geist gehen wird, dass wir mit einem erleichterten Seufzen der Wiederauferstehung des Plattenspielers (wahrscheinlich als iPhonoTM oder so, damit’s nicht zu heftig wird) beiwohnen werden. Was für tolle Sachen man mit Vinyl machen kann, zeigt schon seit Jahren der Klangkünstler Philip Jeck. Zusammen mit Gavin Bryars und Alter Ego ließ er in “The Sinking Of The Titanic” altes Erinnerungsmaterial auf moderne Verarbeitung stoßen, auf seinem grandiosen “Vinyl Coda” setzte er bereits um die Jahrtausendwende Maßstäbe in avantgardistischer Musik für analoges Material. Jetzt erscheint “An Ark For The Listener”, für das Jeck Live-Aufnahmen der letzten 12 Monate verwendet hat und das als Meditation auf Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Gedicht “The Wreck of The Deutschland” angelegt ist. Das muss man aber nicht wissen, um die dunklen, repetitiven Töne Jecks auf sich wirken zu lassen. Auf der Bühne arbeitet er mit Plattenspielern, Casio-Keyboards, Minidisc-Playern (kennt die Jugend gar nicht mehr!), Mixern und Bassgitarren. Gruselig schön. [Tina Manske]

SA:

Gonzo Circus (Belgium):

popmatters (USA):

Philip Jeck’s process alone, of creating records through the use of layers of junk-shop turntables, is fascinating. Each of his records re-imagines the idea of instrument, because though there are keys and bass to be found, in the end it is the spinning records, the hissing roil of them, that takes center stage. An Ark for the Listener, a cycle based on part of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ poem “The Wreck of the Deutchsland”, is another solid accomplishment from the composer, and proof that there’s plenty of variety left in his spinning sound six albums in. Despite its ambient feel, there’s nothing gliding or droning about Jeck’s sound here. This music grinds. It churns. Sometimes, particularly on “The Pilot (Among Our Shoals)” and “Chime, Chime (Rerung)”, it clatters and clangs. The album, with its insistent movement and shifts between swelling noise and negative space, both fits in with, and twists in new directions, the sounds we’ve heard from Jeck before. The one added layer of intrigue here, that Jeck is interpreting his own live performance from an installation in April 2010, does little to add to an already full sound. There’s already plenty to chew on in Jeck’s work, and while this one might not quite match his best, falling short of the mastery of Sand, it is still damned arresting music.

ae mag (Germany):

Eine ganze Gefühlslawine lässt Grammophonalmusiker Philip Jeck auf den Hörer (sic!) los, ehe der Ton sich wie ein Abwasserrohr in die Tiefe windet um letztlich nach Erreichen der Grundquelle in der Dunkelheit zu versickern. Ohne Frage, was Jeck abliefert, ist feinstes Droneunterstandement, in der besten Tradition wie Feine Trinkers Bei Pinkels Daheim, aber ohne den Witz letztgenannterer, was sich hier sparsam zurückhält sind die Quellen aus denen Jeck seine Ableitungen zieht wie Kabelstrippen aus dem verrauchten Erdreich. Glockentöne winden sich in Delays, Drones schwingen unsauber auf der chromatischen Skala, am Ende wird alles in faserigen Hall geworfen, in unzureichend erklärbare Gefühlsbarrieren gepresst, die dem Hörer alleine schon einiges abverlangen. In der Welt von Jeck winden sich gerade die feinen Emotionen wie Schlangen aus ihren Höhlen, um den Wahrnehmenden einzulullen ohne dass er es merkt. Was bleibt ist die Musik, haunting und mysteriös, mit einem traurigen Unterton, als sehne der Klang sich nach der Bestätigung für seine Existenz. Gerade der Opener mit seiner schroffen Figur verlagert sich am Ende in die schönste Quintessenz von »An Ark For The Listener«: der Ausblick auf wenige Momente ungeschminkter Cinemaskopie im Klang, gehüllt in antiquierte Verzerrung. Genau das ist das was Musik ausmacht. Ein äußerst persönlicher Moment in glorifizierter Zierart. 5/5

Uncut (UK):

Laif (Poland):

Beyond the Noize (France):

Ce qui frappe avec les sorties de chez Touch, c’est leur immense cohérence et leur délicatesse artistique. Touch est un label comme on les aime, qui passe au peigne fin ses choix au niveau des artistes, mais aussi au niveau du son des artworks. Un objet de chez Touch est rapidement reconnaissable, et son contenu aussi. Ecueil des musiques avant gardistes et souvent composées de manière conceptuelles, Touch est à la pointe de l’avant garde ambiante. Cette fois ci, le label nous propose un objet de Philip Jeck, qui contient en fait deux différents concepts, donc deux différentes phases de création.

La première phase est An Ark for the listener, qui est une une reflexion sur un verset d’un poème de 1875 :

”With a memory that outrides

The all o water, an ark

For the listener ; for the lingerer with a love glides

Lower than death and the dark ;

A vein for the visiting of the past-prayer, pent in prison,

The-last-breath penitent spirits – the uttermost mark

Our passion-plunged giant risen,

The Christ and the father compassionate, fetched in the storm of

His strides.”

(Gerard Manley Hopkins)

Une ambiance purement aquatique donc, voire même apocalyptique, qui retrace une noyade en cascade. Un artwork expressément choisi pour, avec une installation présente au tate modern, mais surtout cet arrière de pochette terrifiant, photo d’une chute d’eau à Brighton qui retrace le poids des éléments déchainés.

Une grosse introduction qui permet de contextualiser ce travail de titan de Jeck sur ces différentes installations live qui lui ont permis de compiler cet ark for the listener. Un an de lives pour en arriver à extraire les sons présents sur ce disque. Un travail de romain, dans l’agencement et la justesse des sons.

La deuxième phase sont ces deux morceaux finaux, rajoutés à la fin du disque sous le nom de Coda, qui sont en fait un remix d’une suite de sons extraits d’un live et un morceau préparé pour un magazine.

L’unité, vous me direz ? Elle est bien entendu dans la musique et dans son processus créatif. Jeck crée tout à base de vieux lecteurs de musique, qu’il rachète dans des dépôts (objets bons pour la poubelle en gros) et qu’il bidouille pour en tirer toutes sortes de sons. Jeck crée des sons à base de machines et une fois que les réglages lui conviennent il superpose diverses couches, où salit une propre base sonore. Un travail de longue haleine donc, pour tirer une quelconque cohérence.

Pour cet arc de travail, les ”instruments” utilisés sont selon Jeck : ”fidelity record-players, Casio SK1 keyboards, Sony minidisc recorders, Behringer mixers, Ibanez bass guitar, Boss delay pedal and zoom bass effects pedal”. L’univers de Jeck est sur cet ark for the listener translucide, et l’ambiant décharnée que l’on croit squelettique se transforme rapidement en trou noir musical, d’une limpidité extrème. La lourdeur du son est accentué par la chaleur des basses (notamment sur ce Thirtieth guerrier) et les mélodies organiques semblent jouées de sous une étendue d’eau. On vit la noyade des corps, à travers cette chute sonique céleste et la succession des différentes phrases musicale est d’une rare cohérence. Seul défaut de ce corps vivant : certains morceaux sont un peu courts et les bribes d’idées auraient surement gagné dans la recherche de drones plus constants. Sinon, du pain béni pour le corps, et une piqûre de rappel pour ceux qui croyaient que seule la dark ambiant permettait d’atteindre ces sphères. Avec aussi peu de moyens, on croit entendre Inade. [Macho]

Lidove (Czechia):

ODPOSLECHY

Dnes o tom, jak souvisí film Po?átek s elpí?ky z bazaru Kdy? na po?átku devadesát?ch let v?ichni nakupovali p?ehráva?e kompakt?, uspo?ádal liverpoolsk? absolvent v?tvarné akademie Philip Jeck svébytnou akci. Nesla název Vinylové requiem a hrálo tu najednou sto osmdesát gramofon?. Fatální vztah k elpí?ku? Jist?. Jeck po léta “zachra?uje” z vete?nictví desky i gramofony – nejlépe ty jednoduché p?enosné, co mají reproduktor ve víku. Naprosto mu nejde o retro, ale o vyta?ení ?ehosi nového ze zdánliv? uzav?ené minulosti. Hraje na gramofony jako na hudební nástroje: patinovan? zvuk praskajících drá?ek mu slou?í jako materiál, kter? zru?n? p?eskupuje do vlastních voln?ch skladeb. Leto?ní album An Ark For The Listener (vydal lond?nsk? Touch), tedy Archa pro poslucha?e, ukazuje, jak hluboko se Jeck dostal ve své metod?.

Jeckova snov? zpomalená, chv?jící se hudba polopr?svitn?ch vrstev p?ipomíná naslouchání zvuk?m ze v?ech stran: uprost?ed nám?stí, na nevysokém kopci anebo v krajin? rozechv?né v?trem. N?co se po?ád trochu opakuje a vrací (jako na p?eskakující desce), p?es to se valí prom??ující d?je. Tahle hudba vychází z organick?ch model? a nikdy nem??e spadnout do jasné geometrie minimalismu: v?ak taky elpí?kové second handy a vete?nictví p?ipomínají mnohem víc mo?ály, zátoky s naplaveninami a archeologická nalezi?t? ne? newyorskou pravoúhlou uli?ní mapu, na které vyrostli Steve Reich a Phil Glass. (Jejich hudb? se naopak podobají komínky a regály v supermarketech s cédé?ky, ale tam Philip Jeck na lov nechodí.)

Uchopení zvuku a vzpomínek, jaké p?stuje Philip Jeck, prosáklo letos do díla, které ob?hlo zem?kouli: filmové sci-fi Christophera Nolana Po?átek. Ti, kdo ho vid?li, v?dí, ?e v p?íb?hu v??n?ch odchod? do snu se opakovan? vrací píse? v podání Edith Piaf Non, je ne regrette rien. Po premié?e v?ak autor soundtracku, skladatel Hans Zimmer, rozkryl, ?e od ?ansonu odvodil i dal?í hudbu. Zpomalil – a tedy i p?eladil do hlub?ích poloh – doprovod dech? tak, ?e se najednou nám?sí?n? vle?e. Sly?et v hollywoodském trháku hudbu ud?lanou p?es kolísající gramofon, to se nestává ?asto. P?vodn? romantická písni?ka se náhle nestabiln? kymácí a odvádí z lidské zóny.

Sv?t je dnes ur?ován rychl?mi tempy. Hans Zimmer pochopil to, co má ve své hudb? Jeck obsa?eno u? dávno: zpomalit hudbu znamená vzít jí pevné kontury a p?eobsadit. V loutkov?ch filmech typu Vzpoura hra?ek jednají p?edm?ty samy za sebe, nezávisle na sv?t? lidí. Toto je taky hudba, je? jako by sublimovala ze samotn?ch v?cí, které um?lec zastihl bez vlivu ?lov?ka. Ten po?ád jen p?ehlu?uje autentick? jazyk sv?ta: není divu, ?e kdo ho chce sly?et, vyhledává opu?t?né, zapomenuté a necht?né scenerie, stará elpí?ka a p?íru?ní piknikové gramofony.

John Cage nem?l p?íli? rád v?raz experimentální hudba: “Jak?pak experiment,” ?íkal, “vím naprosto p?esn?, co d?lám.” Zdá se, ?e první léta po p?elomu milénia p?inesla sv?tu mohutnou vlnu hudebních experimentátor?. Jen?e t??ko b?t u?edníkem nadosmrti. Muzikanti (v?etn? Philipa Jecka) si ozkou?eli nové principy, fáze pr?zkumu skon?ila – a do?lo na lámání chleba. Je to pro scénu docela siln?, náro?n? moment: nezávazné blbnutí na po?átku je prima, ale zvládn?te moment, kdy máte potvrdit, ?e se vám bude dob?e a dlouho hrát s kartami, co jste si sami vybrali! Album An Ark For The Listener ukazuje, ?e Jeck si svou poetiku nastavil dost ??astn?.

Do gramofonu se dá sáhnout: snad ka?d? si jako dít? zkou?el m?nit rychlosti, skákat s p?enoskou. P?ehráva? kompakt? je oproti tomu nedobytná pevnost. Proto je hudba Philipa Jecka tak blízká relativn? ?irokému publiku: pov??il na um?ní jednu z her na?eho d?tství. [PAVEL KLUSÁK]

Elegy (France):

Signal to Noise (USA):

Rockdeluxe (Spain):

OM (Spain):

Etherreal (France):

Philip Jeck est un artiste reconnu, mais discret, que l’on aura tendance à situer un peu en marge de la scène électronique dont nous parlons en général ici. Il trouve pourtant naturellement sa place sur ces pages où il a d’ailleurs fait l’objet de plusieurs chroniques de concerts, mais c’est la première fois que l’on aborde la production discographique de l’Anglais, fidèle au non moins reconnu label Touch.

En fait on se dira assez rapidement que l’on devrait écouter plus souvent les disques de cet artiste. Restant sur le souvenir de lointains concerts, on avait quelque peu oublié la richesse de la musique de Philip Jeck. Cette chronique terminée on ressortira d’ailleurs très certainement Stoke ou Soaked, une collaboration avec Jacob Kirkegaard publiée en 2002.

On est tout de suite captivé par l’efficacité de l’intro de Pilot/Dark Blue Night, composée d’une sorte de nappe/drone mélodique complètement noyés dans une texture grésillante, une formule assez habituelle de l’artiste qui a toujours su garder une dimension mélodique dans sa musique. Cette intro (qui correspond en réalité à Pilot) sert de fil rouge à l’ensemble de l’album. Un thème récurrent qui, dès la première écoute, a des airs de déjà entendu et qui s’invite à la manière d’un interlude sur Thirtieth/Pilot Reprise, ou en version complète sur The Pilot (Among Our Shoals), ponctué d’étonnantes percussions, une ambiance de fête foraine qui est en faite créée par la manipulation de vieux vinyles.

Si l’on s’attendait à cette ambient feutrée et granuleuse qui parsème l’album (Pilot/Dark Blue Night, Twentyninth ou le délicieux The All Of Water), on est plutôt surpris par l’incursion de ces éléments percussifs, tout comme les tintements abstraits d’une boite à musique qui composent Ark ou les rémanences 70s suggérées par ce qui ressemble aux tourbillons de vieux synthés analogiques sur Dark Rehearsal.

Ces sept premiers titres sont nouveaux, construits à partir d’enregistrements lives piochés sur l’année qui précéda la sortie de l’album. Les deux derniers morceaux sont quant à eux des remixes d’extraits de Suite : Live In Liverpool, un vinyle publié en 2008 en partenariat entre Touch et Autofact Records. L’occasion de (re)découvrir le sublime et envoûtant All That’s Allowed ou le scintillant Chime, Chime.

Une ambient crépitante et vivante. Un disque de toute beauté. 7/8 [Fabrice Allard]

Bodyspace (Spain):

O velho e o mar, o medo e a morte.

Philip Jeck já tem muitos anos de música, desde composições para companhias de dança e teatro a colaborações com artistas como Jah Wobble e Otomo Yoshihide. O espaço que o britânico ocupa nos meandros da electrónica de vanguarda conquistou-o com o seu approach no que toca à criação de uma sonoridade própria; Jeck pega em discos antigos, turntables e pedais de efeitos, rasga sons daqui e dali e cola tudo com um sentido composicional notável, de modo a que nenhum ponto que vagamente se assemelhe ao original permaneça no seu trabalho. Ou seja: DJ Shadow para homens com colhões.

An Ark For The Listener é um disco construído com base num poema de Gerard Manley Hopkins, The Wreck of the Deutschland, sobre o naufrágio de um navio em 1875 e da consequente morte de cinco freiras franciscanas. A música é uma electrónica grave e por vezes assustadora, a aflição enquanto elegia; os mais desabituados esbarrarão porventura nos drones e ruídos que Jeck utiliza para atingir tal efeito, mas os restantes terão aqui um bom exercício de escuta e de meditação. Não é um álbum fácil de se ouvir, mas se existir o mínimo de paciência os resultados serão sem dúvida satisfatórios.

Pois que o intuito será assustar, “Ark” consegue-o; teclados infantis e todo um ambiente sufocante. Depois há “The All of Water”, oito minutos drone que compõem o clímax do disco, e “The Pilot”, que prossegue essa toada, dando por finda a história que se contou. “All That’s Allowed” e “Chime, Chime” são duas remisturas de temas anteriores, do álbum de 2008 Suite: Live In Liverpool, que são igualmente interessantes mas que nada de especial acrescentam. [Paulo Cecílio]

Musique Machine (UK):

An Ark For The Listener is a meditation on verse 33 of Gerald Manley Hopkins poem “The Wreck of the Deutschland,” which concerns the 1875 drowning of 5 Franciscan nuns exiled from Germany. I’m not sure if taking one verse out of a rather long poem works but in case you want to know what verse 33 is here it is:

With a mercy that outrides

The all of water, an ark

For the listener; for the lingerer with a love glides

Lower than death and the dark;

A vein for the visiting of the past-prayer, pent in prison,

The-last-breath penitent spirits—the uttermost mark

Our passion-plungèd giant risen,

The Christ of the Father compassionate, fetched in the storm of his strides

Unfortunately the liner notes don’t give an explanation of why verse 33 and not the whole piece and that would have been useful. An idea of where Philip Jeck is coming from with this album would give more contexts to what you listen to.

For this album Philip Jeck uses Fidelity record players, Casio SK1 keyboards. Minidisc recorders, bass guitar, and various guitar effects pedals.

It’s an interesting album though it has a few moments that just don’t seem to work. I did start to write this review going through each piece part by part but it didn’t really convey how the album sounds. The elements of this that really work are the parts where he sounds not unlike William Basinski on his Melancholia or Disintegration Loops albums.

Slow moving atmospheric and ethereal sounding pieces that sound almost like a slightly skewed warped orchestra on the Titanic or that they come from a dance hall back in the early 1900s. That’s possibly two thirds of the album. There are a few other parts that lead into the Basinski sounding pieces that sound very Zoviet France like. Very loosely wound strings being strummed on an instrument that starts to sound not too dissimilar to church bells chiming. However a couple of the pieces (track 2 “Ark” especially ) just don’t feel as though they work. “Ark” sounds predominantly like someone playing very randomly on a xylophone or glockenspiel and not making anything you’d want to hear again. I think this is an example of where some sort of explanation of what the piece is about would help. For all I know he may be trying to convey a particular emotion of a particular part of the story of the nuns drowning which might make it all blindingly obvious as to why it sounds like it does. But without that sort of information it just comes across as a piece that doesn’t work or fit in. As I say there’s a couple of pieces I feel like that about on this album.

Touch are a label whose catalogue is filled with unusual artists/releases and this one is no exception to that. It’s perhaps not up there with other Jeck things I’ve seen (his installation at the Hayward gallery’s “Sonic Boom” exhibition springs to mind) or heard such as his very first Touch release “Loopholes” but it’s still something I would recommend to anyone with an interest in the work of Philip Jeck. As always with Touch the wonderful pictures on the cover art are by Jon Wozencroft. [Roger Batty]

GoMag (Spain):

Le Temps (Switzerland):

Machina (Poland):