It’s 1981. Punk has arrived and dissipated in one white-hot magnesium flash, but what we now refer to as the post-punk period is very much ablaze, the country’s network of fanzines and burgeoning independent record labels expanding at a furious rate.

Out of this smoulder and smoke, student Jon Wozencroft establishes Touch with his friends Mike Harding, Gary Mouat and Andrew Mackenzie. Over the next 27 years it will become arguably the finest audio-visual label in the world, an imprint whose product, modes of transmission and philosophical concerns embody, but also critique, the fundamental transition from analogue to digital technology which has defined our cultural age. “There was just such great music being produced in 79, 80 and 81,” explains Wozencroft, London-based co-founder and art director of Touch, “and you had that sense of movement in the culture, and also very strong things around it – like film, the development of the Filmmakers’ Co-op, the distribution of art-house films, writing, journalism. The idea that you could bring all of these aspects together had been shown by groups like Cabaret Voltaire, and I just thought, well, what’s the obvious extension of this?

The obvious extension of this was Touch, an audio-visual “publishing project”, which has acted as a curator and disseminator of experimental writing, film, graphic design and music ever cine. Touch is perhaps best known for releasing paradigm-shifting electronic works by Fennesz and Geir Jensson (aka Biosphere), but its range of focus is far wider, its catalogue more rich and varied, than to be described as merely ‘electronica’, or ‘ambient’; the ideas it explores too prescient and important to get stored away in the broom cupboard marked ‘experimental’. And as its owners never tire of asserting, Touch is about more than music: “We’ve always tried to pay attention to all of those invisible feelings and ideas about atmosphere and space and presence that are difficult to talk about and need a context in order to be talked about.” Providing such a context is Wozencroft’s specialty, and his design and editorial work for the label is as much a part of the finished artwork as the music.

“I don’t know if I’d like to start a label now. There was a support system and a desire in culture for difficult music in 1980-1,” Wozencroft explains. “You were just coming out of the back of Public Image’s Metal Box, Joy Division, Gang of Four, Wire – all these bands that were very daring but also very popular. I think the fact that we came out of that scene gave us an idealism and a kind of faith – that you could produce really good stuff and that people would respond to it – which really kept us going through some of the more fallow years, between the early nineties and the early noughties, when music just became so devalued and so much part of a kind of factory floor mechanism rather than a passionate cultural moment.”

Touch’s early releases were cassette magazines, immediately distinguished by the editorial control and attention to detail with which they were presented. The inaugural edition, released in December ’82, featured music from Tuxedomoon, Shostakovitch and New Order’s ‘Video 586’, poetry by Vladimir Mayakovsky, with visual interventions from the likes of Neville Brody, Hipgnosis, Malcolm Garrett, Panny Charrington and The Residents. Subsequent issues boasted contributors as disparate and distinguished as Derek Jarman, John Foxx, Current 93, A Certain Ratio, Peter Saville, Gilbert & George, Einsturzende Neubauten, Cabaret Voltaire and Jon Savage. Around this time, Touch also played a crucial role in the import and distribution of so-called “world” music; indeed, the label’s first LP release was The Egyptian Music by Cairo-based composer and musicologist Soliman Galil.

Though the cassette magazines gradually gave way to CDs as the label’s dominant vessel of expression, their mixed media approach and exploratory values define the imprint to this day. Over the past quarter of a century, Touch has provided a platform for sound artists and musical adventurers like Richard H. Kirk, Geir Jensson, Ryoji Ikeda, Pan Sonic’s Mika Vainio, sometime Sunn O)) collaborator Oren Ambarchi, Chris Watson, routinely providing a visual and material aspect to the sound which is as beautiful and thought-provoking as the sound itself.

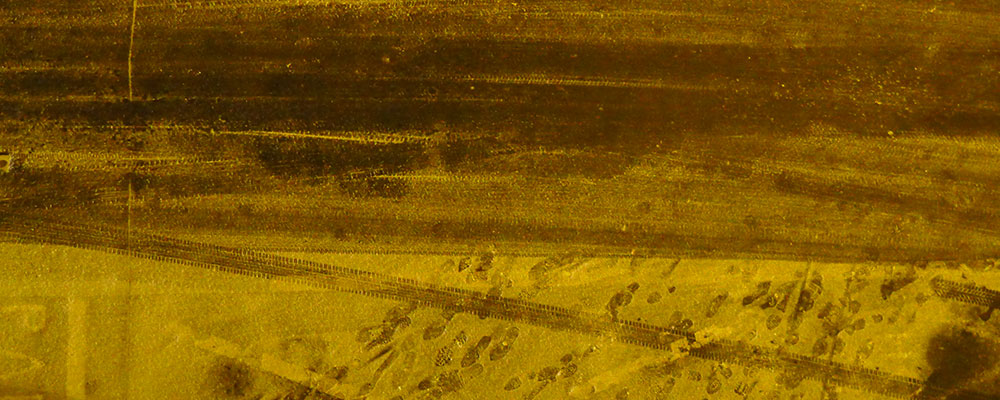

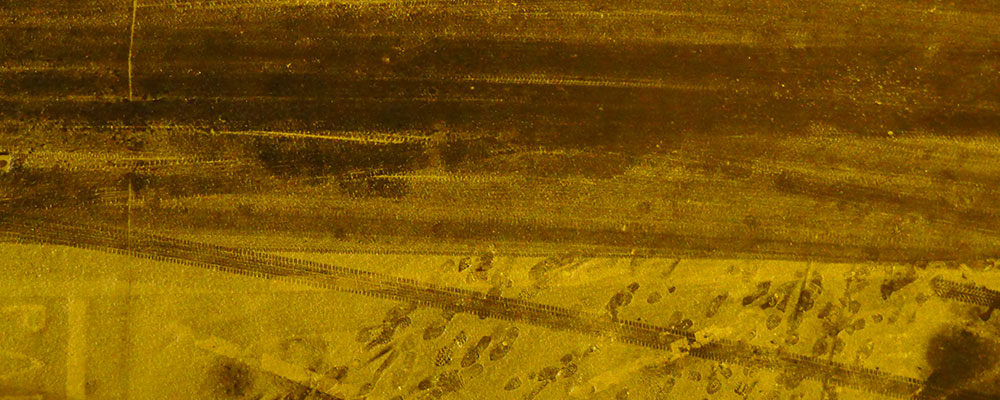

“Aura is the important thing,” Wozencroft explains. “It doesn’t matter where it comes from. It doesn’t have to be packaging, it’s about care, it’s about how you communicate art.” Whether it’s a book, a pamphlet, a cassette, a 7”, LP, CD or even mp3, Touch have always responded to the innate strengths of the given format, and has always sought out new ways to confer value on the musical product. As you can see from the images in these pages, Touch’s visual identity is complex and ever-developing, but nonetheless it’s Wozencroft’s wide-angle, almost supernaturally vivid images of countryside and nature which dominate. Why the pastoral imagery, when so much of the music on the label tends towards the abstract and electronic? “The idea is to give music which is primarily instrumental and abstract some kind of narrative strength. I thought it was important to place the natural, physical landscape alongside the dematerialized world of digital sound, in order to have a critical tension between the two, and to place them both in a human context. “The other thing about my visual work is that you rarely see people in it, because you are invited to put yourself in it, and so it becomes like an open space for this idea of ‘everyman’, rather than something which is trying to commodify you, to make you look at something in a certain way because it’s all about fashion, or clothing, or style, or cool. My work isn’t dealing with any of those codes and signifiers at all, so I suppose it becomes a kind of ecological statement. It’s trying to indicate that there is a bigger world and a larger dialogue out there than what you can hope to reveal within the confines of a digipak.”

In 1996, Touch released the first solo CD by Chris Watson, co-founder of Cabaret Voltaire and The Hafler Trio, former sound recordist with the RSPB and for many BBC Wildlife programmes, including David Attenborough’s Life of Birds. The album, Stepping Into The Dark, comprised field recordings of “special places” – among them Santa Rosa National Park in Costa Rica and Glen Cannich in Scotland – captured using camouflaged microphones. Watson’s art is emblematic of the spirit of Touch: working at the intersection of nature and technology, a curator as much as creator of sound, with a central concern for landscape, be it natural or man-made, and man’s place in that landscape. Watson is one of many contributors to the Spire project, which Wozencroft describes as “a creative conversation with so-thought-of ancient music and culture, using really special places to have collaborations between electronic and advanced musicians, and classical composers, in the context of the church organ – which is one of the biggest instruments ever.”

This is not the only dialogue which Touch has opened up between past and present. Often these dialogues occur at the level of tranmission. A recent project, Touch Sevens, sees the label invite contemporary musicians – not just Touch regulars but also guests, like sometime Sonic Youth member Jim O’Rourke – to produce two sides of music for dissemination on the “disappearing format” of the 7”. Affordably priced, adorned in Wozencroft’s sumptuous artwork and representing the breadth and plurality of the Touch sound, these 7”s are a fantastic entry-point for those as yet uninitiated into.

One established Touch artist who is uniquely concerned with vinyl is Philip Jeck. Jeck is a turntablist, but not in the sense that, say, Cut Chemist or Q-Bert are turntablists. Rather, Jeck uses record-players as instruments of great expressiveness, coaxing sounds from dilapidated vinyl to create his own musical language, a haunting, crackle-heavy sound that shares aesthetic concerns with The Caretaker, Pole and to some extent Burial – put simply, that the dust and dirt in a record’s grooves reveal as much as the music it distorts. It’s an exploration of memory, and of the way we communicate past, without recourse to nostalgia. Wozencroft: “I think the idea that you have to do something ‘new’ all the time is one of the great diseases of contemporary culture. Part of doing something new is also to have a sense of time and tradition and what’s gone before; I think it’s boring as hell to think that everything has to reinvent itself in three month cycles.”

Of course, for all its continuing interest in the ancient and the analogue, few labels have explored the vanguard of “computer music” like Touch. In ’96, the same year as Watson’s solo debut, the label released +/- by Ryoji Ikeda, a foreboding masterpiece of electronic minimalism. 1998 saw the arrival of the Apple Powerbook, and with it the so-called “glitch” movement that, for a time at least, was synonymous with the operations of Touch and its continental friends Raster-Noton and Mego. Christian Fennesz, formerly of Viennese proto-post-rock group Maische, had already established himself as an electronic musician of great repute, but his 1999 album +47° 56′ 37″ -16° 51′ 08 (named after the coordinates of his backyard garden, the site of the open-air studio where the album was created), and subsequent full-lengths Endless Summer (released on Mego) and Venice, remain high-watermarks of electronic music, at once intensely formal and free, expressive, at times even sentimental. His most recent Touch offering was a serene ambient collection recorded with Ryuichi Sakamoto; his next solo album is due later this year.

For all the sonic and graphic innovation digital technology has enabled, Wozencroft remains concerned about its usage, and the artificial, quick-fix DIY mentality that this technology has granted so much modern-day artistic production. “Twenty-five years ago you had to be very determined and dedicated to get music out there. It was difficult to get a record made, it was difficult to get studio space, it was difficult to afford good pressings for your vinyl – which is one of the reasons we used cassettes. “The idea, now, that everything can be done at the touch of a bottom looks, from a distance, to be a very attractive proposition; but it’s just resulted in this glut of things being released. You have be really hard on the editing side of things, and be willing to say, ‘No, that’s not going to work for the label, we’re not going to release that, you can do something better than that. The distinction between playing music and producing and releasing music is an important distinction. Nowadays it’s commonplace for musicians to have their own record companies, which is great, but…It doesn’t allow you to have that objectivity, or the distance, that makes for the best work.”

We shouldn’t forget that Touch is essentially, and emphatically, a DIY undertaking. But for Touch, simply doing it yourself isn’t enough. You have to do yourself and you have to do it well, honoring at all times your founding ideals: “It’s very important to get away from this idea of perfection. What you should look for is refinement, but with mistakes. And frailties. I suppose it’s like writing – the true art of writing isn’t in that stream of consciousness or flash of inspiration at 2am, in so much as it’s in taking out those bits that clog it up, putting fifty pieces of paper in the wastepaper basket and editing something down so that it becomes this very clear and rich statement.” Touch is an example to us all of what can be achieved with collaboration, commitment and an intelligent sense of restraint, or, more accurately, control. Twenty-seven after its inception, the singularity of Touch’s vision, and the multitude of ideas contained therein, is as remarkable as ever. Its history of responding to change, and seriously evolving, without ever giving in to the petty comings and goings of fashion, is infinitely admirable; in contemporary audio-visual art, its successful synthesis of style and substance is without parallel.

© Kiran Sande. Originally published in FACT Magazine, issue 27 – August/September 2008.