Double Vinyl + Download – 13 tracks – 64mins

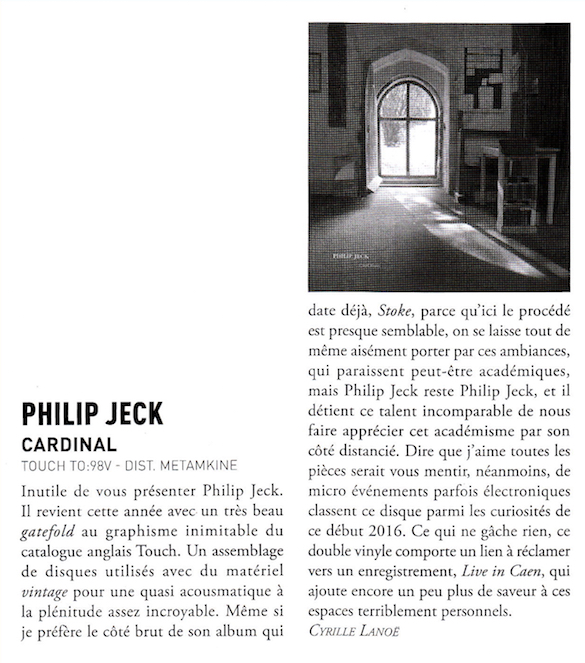

Photography and artwork by Jon Wozencroft

Cut by Jason at Transition

Track listing:

Side 1.

Fleeing

Saint Pancras

Barrow in Furness (open thy hand wide)

Reverse Jersey

Side 2.

… bend the knee 1

Called In

Brief

Side 3.

Broke Up

… bend the knee 5

Called Again

Side 4.

And Over Again

The Station View

Saint Pancras (the one that holds everything)

This album comes with a free download of Philip Jeck “Live in Caen”, recorded by Franck Dubois on 28th February 2015 at Impressions Multiples #4 (ésam Caen/Cherbourg) with thanks to Thierry Weyd.

“… and they sparkled like burnished brass”*

Out of the depths of our complaints, it could be all so simple. To be never fooled by the finesse of a long-yearned for solidity, but in the momentary aplomb of a sleepy walk threading through familiar streets we’d hum our way, alto, baritone and tenor toward some harmonious end. An effect like some wonderful recollection of one or other of those technicolour movies. Not real for sure, but if you are in the mood….

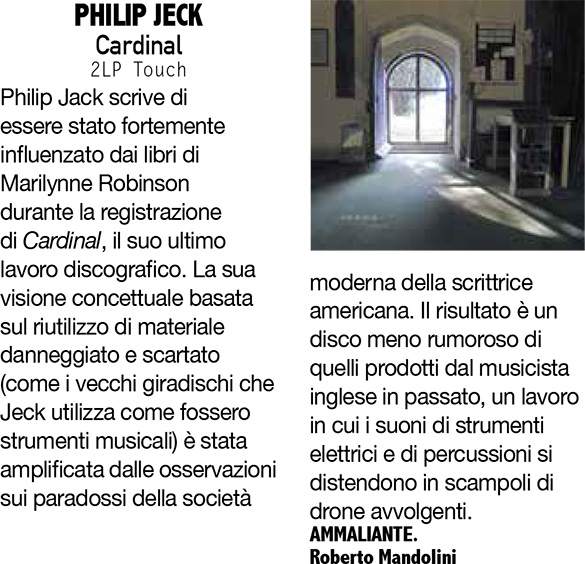

I would like to acknowledge the influence the writer Marilynne Robinson has had on this work. I would recommend reading any/all of her four novels and also “When I was a Child I Read Books” [Virago, 2012]. This collection of essays include “Austerity as Ideology”, which dissects prevailing economic thinking, and “Open Thy Hand Wide…” which continues with a celebration of liberal thinking as Generosity (and also turned over my received knowledge of Calvinism). Her ability to convey a love of humanity and sense of wonder about the great mystery of existence in her writing has, since I first read a book of hers, found a way into the way I think about my work – not illustrating but meditating upon.

“After all, it’s [humankind] debts are only to itself.” (Marilynne Robinson)

To make this record I used Fidelity record players, Casio Keyboards, Ibanez bass guitar, Sony minidisc players, Ibanez and Zoom effects pedals, assorted percussion, a Behringer mixer and it was edited at home with minidisc players and on a laptop computer.

I would like to thank Octopus Collective’s Full Of Noise Festival where “The Station View” and “Barrow in Furness” were first recorded. Guy Madden and InMute’14, Athens who commissioned me to play a live soundtrack to Guy’s film “Cowards Bend the Knee” [2003]. “… bend the knee 1” and “… bend the knee 5” are reworked sections from that performance.

The two Saint Pancras Tracks are remixes of part a performance at St Pancras Church, London; an earlier version was made for “Touch. 30 years and counting” [Touch, 2012]. Saint Pancras (Latin: Sanctus Pancratius; Greek: Ἅγιος Παγκράτιος) was a Roman citizen who converted to Christianity, and was beheaded for his faith at the age of just 14 around the year 304 AD. His name in Greek literally means “the one that holds everything”.

“Called in” is an edit of a live performance at Spire in Krems, Austria [Kontraste Festival, 2013]. “Reverse Jersey” is an edit of a live performance for WFMU in New Jersey as part of Touch.30 [2012].

“Fleeting”, “Brief”, “Broke Up”, “Called Again” and “Over Again” were made at home in Liverpool between 2012 and 2015.

Thanks to everyone who has invited me to play, to Daniel Blumin at WFMU, to Mike Harding for the original recordings of “Called in” and “Saint Pancras” and a belated thank you to Jacob Kirkegaard for playing the chimes on “Ark” from “An Ark for the Listener” [Touch, 2010].

“… weeping for the wrongs we cannot undo.”

Philip Jeck, April 2015

*from The Book of Ezekiel

Reviews:

Dusted (USA):

Philip Jeck’s music is both immediate and intangible. Partly this is due to the source material: salvaged vinyl records, used despite (indeed because of) their numerous degradations, which are processed and filtered through effects until they achieve new, unexpected rhythms, melodies and structures. By looping and assembling these faded relics, as well as combining them with other instruments, Jeck has over the last 20 years amassed a potent body of work that lingers in the space between noise, drone and ambient, always beautiful but often fleeting, as crackles and hiss briefly reveal the ghosts of what once was. Cardinal, his first album since 2010’s seminal An Ark for the Listener, continues in the vein of his previous releases, and indeed can be seen as the most exemplary encapsulation since Stoke in 2002.

In comparison to An Ark.., which was inspired by the sinking of the SS Deutschland and involved meditations on the power of the sea, Cardinal doesn’t have a clear guiding theme from the start, but slowly unveils its secrets the more one listens. A lot of the tracks are relatively brief. Opener “Fleeing” surges out of the speakers under a wave of crystalline drone and a swooping keyboard line, harking back in some way to An Ark…. Its textures sound remarkably close to the crashes of waves on the beach. Jeck is in elegiac mood, with each track heavy with emotion. Two tracks are named for Greek Catholic convert Saint Pancras, who was beheaded for his faith by the Romans, whilst the liner notes quote the Book of Ezekiel and acknowledge the influence of American author and congregationalist Marilynne Robinson. If this suggests that Philip Jeck has made a faith-based record, the music itself veils any religiosity in harmonic smoke and mirrors, following a meandering path where track title refer to one another but with unresolved meaning.

As an artist, Jeck is endlessly contemplative. Live, he sits or stands hunched over his turntables and gadgets, lost in the process of composition. Here, as on other albums, he makes references to places (Jersey, Barrow in Furness), but they could be places he’s performed his compositions just as much as ruminations on the landscapes they evoke. Or they could be both. Plotting a path through the nebulous clouds of fuzzy atmospherics, wavering synth lines and hinted meanings is futile, for this music to be absorbed rather than focused on. Tracks like “Barrow in Furness (open thy hand wide)”, “Reverse Jersey” and “Saint Pancras (the one that holds everything)” manage to be both expansive and intimate, overflowing with detail yet emotionally stirring. On other occasions, Jeck edges into darker territory (the use of bass, albeit highly modified, is interesting in this respect), such as on “…bend the knee”, where the warped vinyl throws up unnerving, unidentifiable sounds and twisted layers of gritty mulch intrude on the beatific calm of the synths.

Because of the tools he uses, and the results they produce, Philip Jeck has often been lumped in with the “hauntology” non-scene of the last few years, regardless of the fact that he’s been doing this for decades. It possibly has something to do with his involvement in recent productions of that most ghostly of modern compositions, Gavin Bryars’ The Sinking of the Titanic and occasional similarities with another English eccentric, The Caretaker. Either way, it’s a disservice to Jeck whose work is too esoteric, too personal and too complex to belong to any genre. He’s an artist who stands alone, patiently sending us communiqués from lost and imagined lands. Thank you, Philip. [Joseph Burnett]

tinymixtapes (USA):

Philip Jeck returns with Cardinal on Touch, commits lesser-known sin of being too talented

The papal craze was palpable across huge swaths of the United States last week, and is it any wonder why? Organized religion is awesome, especially when particular denominations are characterized by hierarchies and one person at the top who’s conceivably a Batman nemesis, according to his contrastingly bright and exposed “mobile.” Obviously, you don’t achieve that type of cultural status without a significant history, and it’s a Christian history that British renaissance man (and notable composer) Philip Jeck is at least mildly acknowledging with the release of Cardinal, his newest album for Touch. The “Saint Pancras” tracks are in reference to the Roman lad who converted to Christianity and was promptly beheaded for his beliefs in the year 304 AD. So there’s that.

Listen to the latter “Saint Pancras” track below, and feel free to be immediately struck by the ancient drone reminiscent of Xela’s similarly-themed In Bocca Al Lupo. It’s too early for comparisons to Jeck’s prior An Ark for the Listener, but what we expect is ambiguous ambience, inspired further by the writings of American author Marilynne Robinson. Among other things, she wrote about the importance of imagination to communal progress.

Aural Aggravation (net):

Sometimes, the idea that things happen by mere coincidence simply doesn’t seem satisfactory. In the age of hyper-information, it seems almost inevitable that fragments from the most disparate sources will collide. And so it was that last week, I began reading Mark Fisher’s book, Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. In the first few pages, Fisher, (who I now know has provided substantial coverage of Jeck over the years, particularly in writing for ‘The Wire’) frames Jeck’s work in the context of the concept of ‘hauntology’, a term coined by Jacques Derrida to explain the eerie nostalgia and uncanny sense of loss prevalent in his work. The name seemed familiar, but I was initially unable to place it, before remembering an email received a day or so before containing a list of upcoming new releases available for download.

Of course, it’s impossible for me to listen to ‘Cardinal’ without searching for the details, the ways in which the compositions evoke notions of nostalgia and a sense of loss as refracted through the prisms of theoretical discourse and personal interpretation. But ‘Cardinal’ is, however you approach it, an album steeped in evocative vibrations, a collection of instrumental works which are almost spectral in their presence at times.

Of the album, Jeck explains, “To make this record I used Fidelity record players, Casio Keyboards, Ibanez bass guitar, Sony minidisc players, Ibanez and Zoom effects pedals, assorted percussion, a Behringer mixer and it was edited it at home with minidisc players and on a laptop computer.” He makes it sound so simple, and says nothing of the infinite layers the music on the resulting record contains.

It begins with a huge cathedral of sound, a shifting sonic mass which surges and swells and fills the room, enveloping the listener, to be displaced as it fades into more subtle drama. Eddying sonic mists buzz and cluster, sheltering in corners of sepulchral echoes. Time warps, speeds and slows as notes are stretched, elongated and twisted as they spin in the air.

It’s commonplace for the tracks on albums which broadly fit into the ‘ambient’ territory Jeck explores to bleed together, for the passages to be segued to form longer tracks which twist and mutate, transitioning, leading the listener on an internal journey directed by the soundtrack. ‘Cardinal’ jars the senses and confounds genre expectations: his comparatively short pieces – of which there are 13 here, many of which are under five minutes in duration – fade out or dissipate into nothing, leaving the listener to squirm through the moments of silence which separate them.

‘Called In’ – the album’s longest track by some margin at almost nine and a half minutes – finds fragments of stolen, unidentifiable, melodies scratch through an amorphous hum which at times resembles Gregorian chants slowed to near stasis, with screeds of chilling whistles and high-pitched drones making fleeting flights over the swamps below. ‘Broke Up’, too, finds spectral slivers emerging from a low-level hum which hangs like dry ice

It’s an immense work, deep, rich and evocative. The bonus inclusion of a free download of a 42-minute live recording, ‘Live in Caen’, captured in February 2015, is extremely worthwhile: while the depth and texture of Jeck’s work is perhaps best appreciated in its studio form, his live set – which dares to explore hushed tones to the point of silence in an time of perpetual noise – shows he’s more than capable of creating a rarefied atmosphere in an alternative setting. [Christopher Nosnibor]

SPEX (Germany):

Früher oder später stellen sich leichte Jenseits-Assoziationen ein. Ob man auf die Knie geht oder nicht, bleibt einem selbst überlassen.

Philip Jeck wählt eine gemächliche Gangart. Der für seine monumentalen Plattenspieler-Loops beliebte Klangkünstler erzeugt mit überschaubaren Mitteln eine barocke Fülle, gegen die sich die Exerzitien im Dschungel seines Landsmannes Anthony Child recht asketisch ausnehmen. Cardinal lässt diese klangliche Pracht, die aus einander überlagernden, von Jeck mit Effektpedalen bearbeiteten repetitiven Schichten besteht, wie sakrale Musik erscheinen. Das wird nicht nur im Albumtitel angedeutet, sondern auch in Stücken wie »Saint Pancras« oder »… Bends The Knee« mit ihren Anspielungen an Topoi der katholischen Konfession.

Versenkungsmusik also auch bei Philip Jeck, genauso kitschfrei und hintergrunduntauglich wie die von Child, wenngleich mit völlig anderer Wirkung. Es mögen die Orgelklänge sein, die Jecks Collagen immer wieder heraufbeschwören, mit ihren kathedralenhaft weiten Räumen, jedenfalls stellen sich früher oder später leichte Jenseits-Assoziationen ein. Was gar nichts Verkehrtes ist. Ob man auf die Knie geht oder nicht, bleibt einem schließlich selbst überlassen.

The Wire (UK):

kindamuzik (Netherlands):

Verspreid door de zaal staan draaitafels die op diverse snelheden draaien, oude platen erop en dan maakt Philip Jeck daar samples van, hink-stap-springend tussen de apparaten, draaiend aan knoppen, manipulerend met laptop en keyboard. Dat is min of meer ‘s mans inmiddels geijkte modus operandi. Op Cardinal komen daar nog een paar minidiskspelers bij en een basgitaar. En nu komt het: verder verwijderd van Squarepusher of DJ Shadow kun je nauwelijks uitkomen.

Als een klaroenstoot van opgepoetst koper galmt de sacrale gloed van Cardinal de toehoorder tegemoet. Jecks sluimerende gevoel van massieve soliditeit maakt zich al snel meester van verdichte geluidsmassa’s waarin de verschillende constituerende elementen niet langer aan te wijzen zijn. De amorfe symfonie waggelt als in een slaapwandeling rond, met net genoeg houvast en herkenningspunten om een idee van herinnering aan te raken. Vreemd of bevreemdend is Jecks werk immers hoogstzelden.

Tegenover de gedragen, majesteitelijke toonzetting met aards fundament, plaatst Jeck een gulle dosis futuristische projectie. Geen gekke visioenen die niet thuis te brengen zijn, maar juist extrapolaties van het gekende naar potentiële (klank)werelden die niet eens zo bizar ver buiten het huidige bereik liggen. Lichtelijk ambigu dus weet Jeck knap te werken met een nostalgie voor straks en tegelijk dobbelt hij in een spel van af-, in- en verbeelding van toen.

Cardinal voert nóg een balanceeract uit op het snijvlak van oneindige expansie en focus tot op een brandpunt. Als vele delen die tellen voor één verhaal, als één kluwen die uiteen te rafelen zou kunnen zijn in tig geschiedenissen. Mist, echo, uitrekking en verlenging, perspectivische vernauwing en verkorting, opklaring en keiharde reflectie: ze buigen tijd en ruimte in een vorm van ambient die onmiddellijk tactiel is. Jeck waardeert degradatie van analoge materialen op tot de artistieke materie die onder handen genomen wordt. Tegelijkertijd vergruist hij progressie en het schijnbaar eeuwigdurend onfeilbare van het digitale domein met atonale horten, abstracte stoten, desintegrerende glitch en relieken van ruis. Nooit: steeds verder weg. Altijd: net binnen handbereik. [Sven Schlijper]

Pitchfork (USA):

At their best, the records of experimental British composer and producer Philip Jeck can make you reimagine the way you hear the world. For most of his career, Jeck has used the record and the record player as both primary inspiration and chief instrument. He processes the static sounds archived on forgotten LPs, sampling and obfuscating the source material until it yields and blurs into new pieces. Though he uses little but effects pedals and processors to transmogrify the music, it can seem at times that Jeck physically warps the grooves themselves, turning concentric circles into Catherine wheels or paisley vectors or interconnected figure eights. If hip-hop’s architects sampled aging sounds to create their own modern world, Jeck uses many of the same tools to create an alternate, individual one that he then invites you to enter.

Jeck had been at this for decades when, 13 years ago, he seemed to find an enviable stride. Released between 2002 and 2008, a triptych of records—Stoke, 7, and Sand—turned his tests into solo turntable symphonies, fully formed compositions meant to be inhabited and analyzed. Jeck merged the audio on the records with the essence of the records, creating new music that popped and cracked beneath the charm of vinyl antiquity. The process seemed to break linear time by giving a universe of lost voices and performances new life at once. You, the listener, went away with Jeck and his record-store finds for a pleasant spell.

But on Cardinal, Jeck’s first new album in five years, that motion and those feelings have calcified a bit. The edges of his sources and samples have hardened, as though he’s confronting the harsh exigencies of the moment rather than escaping to the drift and peace of fantasy. The voices and instruments Jeck once built around slink into the background here, ceding instead to an unexpectedly discomfiting vision. Brittle dins and soft tones, beautiful drones and static shocks participate in a theater of revolving reality and intentional violence.

Jeck indeed created Cardinal with turntables, a technique best heard here through the fractured loop that anchors “Broke Up” or the sunbaked wobble that defines “The Station View”. These 13 tracks, however, often feel powered more by their accessories—”Casio keyboards, Ibanez bass guitar, Sony MiniDisc players, Ibanez and Zoom effects pedals, assorted percussion, a Behringer mixer,” he lists—than the source records. There are jarring moments, as during the menacing “Brief” or the lurid “Called In”, that suggest Jeck has suddenly slammed his palm against a distortion pedal, like some much younger noise lord gunning for the set’s climax. During “Saint Pancras”, he seems to shake sleigh bells in the distance; pitted against the neon whirr of his electronics, the addition is strangely disconcerting, like a threat voiced from the lips of a longtime ally.

That is the prevailing sentiment of Cardinal, an album where Jeck’s general sense of wonder slips toward dystopian bewilderment. The move makes for a more fragmented listen than expected from Jeck, whose albums are typically immersive and enchanting. Still, the transition comes with unlikely rewards. Rendered in short spans that overlap until they form casual rhythms, the hovering bass and shredded treble of the terrific, terrifying “…bends the knee 1” recall the successes of the Haxan Cloak’s Excavation. During “Barrow in Furness (open thy hand wide)”, Jeck slowly mutates a simple carousel melody until it becomes a dense web of ghastly oscillations, a little like Prurient’s electro phase. Yes, those are surprising references for a British sexagenarian with highbrow bona fides, but again, Jeck’s music has always recast the established world in a singular image. Does it come as any mystery that, now more than ever, he would conjure a setting as or more odious than our own?

Records are now in vogue in ways they’ve never been during Jeck’s career. For decades, he repurposed a medium that seemed bound for obsolescence. At times, his use of the LP felt like a moral imperative, a valiant attempt to spin voices and ideas and forms that might be lost. But records, of course, have become such desirable commodities that it’s now difficult to have them made due to an overburdened market that once seemed destined for dismantling. It’s fitting, then, that this is one of the least turntable-centric albums of Jeck’s career, rendered so that you may be able to hear it all without guessing at the signal path at all. Rather than try to stake some here-first claim with vinyl or turn his past with it into new cachet or credibility, Jeck has used the turntable as a platform for exploring larger sounds and asking bigger questions. Cardinal is a break in his once clear direction, and it’s not his most cohesive album. But it is a logical and necessary leap for Jeck, who has always turned at oblique angles so as to reorder the sounds around him. [Grayson Haver Currin]

SilenceAndSound (France):

Avec son nouvel opus Cardinal, influencé / inspiré par l’oeuvre de l’écrivaine Marilynne Robinson, le compositeur de musique expérimentale Philip Jeck livre un concentré de recueillement contemplatif à l’approche résolument introspective. Construit à la manière de mantras stellaires, il nous convie à une succession d’émotions étranges et familères, aux couleurs déviantes et singulières. Utilisant les platines comme instruments de composition, pour les travailler et en extraire des substances transversales, il nous invite à de nouvelles expériences auditives, qui ne sont pas sans rappeler certains travaux de Pierre Schaeffer et du GRM, plongeant nos sens dans de nouvelles contrées musicales, au dépouillement squelettique gorgées d’effets multiples, où instruments (basse, synthé casio, pédales d’effets) et technologie fondent ensemble, pour offrir un liquide suave aux émanations aériennes. Cardinal ralentit le temps, joue avec l’espace, catapultant des mélodies fantômatiques sur des murs lacérés, imprégnés d’énergie fluide. Admirable.

hhv (Germany):

Philip Jeck macht mit einer Menge Schrott ziemlich unheimliche Musik. Sein Hauptinstrument sind ausrangierte Plattenspieler, die er zusammensammelt. Mit bis zu 80 Turntables macht er neue Musik aus alter. Seine Musik ist also schon von Anfang mehr als nur das, sie ist gleichzeitig Installationskunst. Manchmal aber reduziert sich der auch als Choreograph tätige Brite jedoch auf ein weniger opulentes Set-Up und die eine Kunst: Musik. Obwohl die nicht so klingt. »Cardinal« wurde natürlich auch mit Plattenspielern aufgenommen, welche Platten Jeck aber damit abspielte, verrät er nicht. Herauszuhören ist das aus dem bedrohlichen Grummeln und den kratzigen Drones seines – je nach Zählweise – zehnten Studioalbums sowieso nicht, ebenso wenig also wie die von ihm zusätzlich verwendeten Instrumente: Casio-Keyboards oder ein Ibanez-Bass sind kaum auszumachen. Denn wie auch sein ehemaligen Kollaborateur Markus Popp alias Oval entsteht Jecks musikalische Handschrift nicht in der Musik an sich, sondern in der Bricolage von Sounds. Effektgeräte, ein zusätzlicher Minidisc-Player und letztlich ein Laptop wurden bei der Produktion von »Cardinal« ebenfalls eingesetzt. Mit denen verfremdet Jeck sein Ausgangsmaterial und setzt es dann auf eine Art zusammen, die als fertiges Produkt keine Rückschlüsse mehr auf ihre Ursprünge zulässt. »Cardinal« klingt, als hätte jemand die amorphe Silhouette einer kompletten Schrotthalde in Klang verwandelt: Es gleißt metallisch, dröhnt unbekümmert und macht den Eindruck der Menschenleere. Damit treibt Jeck das Programm von geistesverwandten Konzeptlern wie Leyland James Kirby alias The Caretaker noch weiter voran. Wo bei Kirby nämlich die geisterhafte Atmosphäre aus verschwommenen Erinnerungen an diese oder jene Melodie evoziert wird, radiert »Cardinal« alle Affekte aus. Zurück bleibt nur ein Krach, der keinen Urheber zu haben scheint. Wie viel anders und weniger beeindruckend die als Download beigegebene, 40minütige Live-Aufnahme aus dem französischen Caen doch klingt, die noch weitgehend musikalische Motive zulässt. Am großartigsten ist Jecks Musik allerdings, wenn sie nicht nach Musik klingt. Was gibt es schon Unheimlicheres als das? [Kristoffer Cornils]

Aquarius Records (USA):

Five years we have had to wait for a new Phillip Jeck album; and with Cardinal, Jeck delivers yet another masterpiece of thick sonic impressionism, roughly crafted on his vintage turntables and filtered through an array of electronic devices. The textures, the melodies, and the slow languorous pacing of Cardinal has all the hallmarks of a great Phillip Jeck record, including the opaque layering of deconstructed and decontextualized sounds, all coalescing into majestic, sublime concentrations of hiss, murmur, and smear. On Cardinal, much of the recognizable elements of the crackly vinyl and the equally antiquated record players are sublimated within a deep plunge into a mysterious sonic swells that could be the fragments of Jack Torrence’s haunted ballroom hallucinations.

The massive oceanic wall that tumbles through the opening number “Fleeting”, with its modulated shimmer and riptide undercurrents transcends all of the source material into a cinematic sustained crescendo of raw pathos. The slow deceleration of clouded tones and drones found on “Reverse Jersey” tumbles into one of two tracks of diaphanous swirl entitled “…bends the knee” fluttering some of the rare bits of the vinyl’s inlaid melodies into the mix. An unplaceable arabesque here. A fugue from a string quartet there. And then we sporadically hear Jeck throttling his bass guitar as another harmonic component to his compositions. He mostly keeps a Bohren & Der Club of Gore slippery noir vibe, whilst mixing these deep-end notes into his sometimes ominous and always gorgeous elegies for decayed sound.

Titel (Germany):

This week we’ll finish with the long-awaited return of sound sculptor and electronic genius Philip Jeck. Cardinal, his first LP in five years is, apparently, inspired by the work of the author Marilynne Robinson and finds the producer using a mixture of charity shop records and instruments to create a fully realised world. Best heard with your mind open and your eyes closed, the album’s woozy ambiance and epic soundscapes whisk the listener to desolate landscapes, forbidding corridors and places filled with majesty and decay. Glacial drones, hushed percussion and the mere hint of a melody form the foundation of much of the record, with Barrow In Furness (Open Thy Hand Wide), Broke Up and Called Again highlights for me. Fans of value for money will be in for a treat as well since the album also comes with a free download of a live set by Philip Jeck playing in Caen. Long, fragile and luxurious, this is about as close to classical music as techno gets. [John Bittels]

SPEX (Germany):

Blow Up (Italy):

Other Music (USA):

On his new album of static drizzle and ingenious wizardry, British composer and sound sculptor Philip Jeck continues his ongoing search for new sounds and innovative musical processes. Over the past 30 years, Jeck has proven to possess an extraordinary flair for playing disused, degraded vinyl and record players as instruments, processing and filtering their sounds through effects until they produce unexpected rhythms, melodies, and textures. This has resulted in timeless, classic statements, such as his Stoke full-length album from 2002, or his celebrated 2007 collaboration with Gavin Bryars on the latter’s monumental new recording of The Sinking of the Titanic. And now there’s Cardinal, his latest exploration of degradation that traces the transformative potential of derelict technologies. Upon first listen, the album’s brief, conclusive tracks seem to depart from the well-versed theme behind Jeck’s previous record, An Ark for the Listener. But slowly, patiently even, it builds up a coherent, closing statement that opens up a new reality of imagination and loss. Abandoning the vinyl cracks and signal paths that characterize his best-known works, Cardinal explores a larger sonic universe that feels both urgent and oblique. [Niels van Tomme]

MOJO (UK):

tinymixtapes (USA):

I think that Philip Jeck’s music has always been about the cruelty of turntables, especially so on Cardinal. When I say cruelty, I’m talking about how turntablism confronts impossibility with the labored intensity of cataloging a library or climbing a mountain. Cardinal gets physical in that way, its songs made from pillars of chalcedony, formed from masses of darkness and brilliance, all of it moving slowly at the speed of hot fudge.

I listen to Cardinal and head into its deep cave and arrive in the middle of a record store or a farmhouse, a bunch of clues on my scent trail, just like that one scene in A Nightmare Before Christmas with those doors in the trees. You pick a song and dissolve into it, the crackles supporting your soul, the needle spinning the amplified dust. The world becomes sound, the sound becomes a world, the visible and invisible worlds bisect each other, and whatever worlds you live in rotate there too, inside the music, amplified like the wrinkles on a face, the yellowish tinge of a book, or the crinkles of a photograph. Time goes on, moving, and old age frightens the young. Using old material, as Jeck does here, summons ghosts. Ghosts come out of the turntables, ridiculously amorphous and violent. But then the music quiets down, suggesting the placidity of brooks and cathedrals, turning into vast slabs of vintage matter, processed beyond belief, almost unrecognizable, almost illusionary.

Cardinal blows vast. At over an hour long, it feels encyclopedic. It dumps us into a gorgeous trash heap or situates us in a long session of talking, a BBQ, a beach, a porch, a war, a magazine, a book made entirely of margin notes, like Nabokov’s Pale Fire. Patterns dissolve into ultraviolet light, into an overflowing blizzard of a face. Man-made cobwebs of sound — purple here, green there — leisure in an overgrown garden. Jeck’s remoteness — and also his presence — on his records makes us wonder why he does what he does. Why still do it, I wonder, when you could probably do the same thing easier in a digital setup? Why let the cruelty of the turntable punish you underneath its gargantuan accumulation? (I ask these questions rhetorically, of course.)

I can’t help but think that, even though I’ve never been to England, it feels like Jeck makes music to explain England to us; Jeck’s whole entire oeuvre might act on that impulse. But Cardinal doesn’t describe anything English in specific; it just mimics English ambience, that kind of small-town sluggishness that oftentimes comes coupled by the historical presence of architecture and over-played cultural idioms. Cardinal turns into big, warm ponds to swim across: invitations to remember history, invitations to depart history. It suggests short brilliant ponds, a bright flash of lightning on a barn’s roof on the horizon, then industrial nothingness, continually interrupted by doorbells and telephone poles. It suggests a music that investigates the slippages of remembering. I think it works, but at the same time, I think that we’ve all been here before.

Rockerilla (Italy):

Felt Hat (web):

Philip Jeck could be called a veteran of minimalist, droney and atmospheric turntablistic ambient. He embellishes his arrangements and his brush strokes very skillfully using turntables, lo-fi keyboard, bass guitar, obsolete technology like mini discs to embrace some deeper aspects of creation.

It is beyond the term of “experimental” and as he build himself an interesting niche – it is definitely a private and intimate world of ambience within a delicate sphere of personal inner voyage not distorted at all by anything that is pompous and anything that bears the resemblance of so much overrated emblem of “spiritual journey” or indviduation in new agey type.

You can listen to it while in the middle of a outburst of consumeristic, hungry vow of being true to your senses. You can try to deplore it and leave it as it is.

My suggestion is – tune yourself into it, it is truly great stuff – not an ounce of boring repetitism from the mouth of an experienced veteran.

Carnage News (Italy):

Philip Jeck, il suonatore di giradischi, abbandona quella strada. Da suoni modificati passa a suoni generati; cambia supporto e utilizza strumenti e non lascia esclusivamente che il solco e la puntina scorrano mentre lui manomette i suoni con pedali o multieffetto.

Nossignore, stavolta le cose cambiano e la svolta si sente tutta. Ma sentiamo come introduce la questione il Nostro: “To make this record I used Fidelity record players, Casio Keyboards, Ibanez bass guitar, Sony minidisc players, Ibanez and Zoom effects pedals, assorted percussion, a Behringer mixer and it was edited it at home with minidisc players and on a laptop computer”. Influenzato dal lavoro della scrittrice Marylinne Robinson, l’economia della sua musica si basa sulla generosità, (piuttosto che sulla povertà come i lavori precedenti). Non che povertà e generosità si escludano (generalmente il percorso verso la povertà, che non è pauperismo, passa dalla generosità), anzi, entrambi contribuiscono alla generazione di un nuovo modo di pensare, che lascia da parte i propri “-ismi” per farsi libero.

Cardinal è un lavoro complesso, forse così complesso che non può essere caratterizzato, e forse questa è la pecca del disco . Se, difatti, i precedenti lavori di Jeck erano caratterizzati dal suo suono un suono fatto di polvere, sottovoce, lento e inesorabile, ora siamo invece al cesellamento dei mondi sinfonici ambient del disco: Saint Pancras, con i suoi tape echoes, o Barrow in Furness (Open thy hand wide, un continuo ampliarsi e contrarsi di delay. Momento interessante di Cardinal è Reverse Jersey, in continua cambio di pitch, elastica e vaporosa, che anticipa la lugubre …bends the knee 1 o l’agghiacciante Called In, in cui i tappeti, ottenuti da una saturazione e sublimazione dei suoni di sorgente, avvolgono l’ascoltatore e si mescolano tra loro nella generazioni di bordoni continui e transeunti, che trascolorano senza sosta. Brief ritorna ai suoi vecchi suoni, ma l’escavazione va ancora più in profondità, con invasioni di distorsioni, anticipando l’araba Broke Up, illuminata sulla via di Damasco. And Over Again, con il suono influenzato dai suoni attuali (da Lee Gamble a Oneohtrix Point Never) di lunghi tappeti che anticipano i sussurri post-industrial/cyber di The Station View.

Cardinal butta molta carne al fuoco, propone una svolta nel suono dell’autore, che cambia così tanto da non sembrare più il solito Philip Jeck. E questo non è sempre un male, soprattutto se le radici della propria estetica non vengono tolte tout court, ma continuano a rimanere salde e a entrare sempre di più nell’humus creativo con il linguaggio che lo ha visto crescere. [Riccardo Gorone]

Revue et Corrigé (France):