Digipak CD + 24pp booklet

4 tracks – 58:28

Photography: Maggie Watson

Art direction & Design: Jon Wozencroft

Sound mastering by Denis Blackham, Skye

Texts by Chris Watson, Dr David Petts, Lecturer in Archaeology/Associate Director of the Institute of Mediæval and Renaissance Studies

Dept. of Archaeology

Durham University, and Dr Fiona Gameson, St Cuthbert’s Society, Durham

•

The Sounds of Lindisfarne and the Gospels

To celebrate the exhibition of the Lindisfarne Gospels at Durham Cathedral from July to September 2013, award–winning wildlife sound recordist Chris Watson has researched the sonic environment of the Holy Island as it might have been experienced by St. Cuthbert in 700 A.D.

Track listing:

1. Winter

2. Lencten

3. Sumor

4. Haerfest

He writes:

A 7th Century Soundscape of Lindisfarne

Throughout human history artists have been influenced by their surroundings and the sounds of the landscape they inhabit. When Eadfrith, the Bishop of Lindisfarne, was writing and illustrating the Lindisfarne Gospels on that island during the late 7th C. and early 8th C. he would have been immersed in the sounds of Holy Island whilst he created this remarkable work. This production aims to reflect upon the daily and seasonal aspects of the evolving variety of ambient sounds that accompanied life and work during that period of exceptional thought and creativity.

Chris Watson – sound recordist – www.chriswatson.net

With thanks to Professor Veronica Strang, Executive Director, Institute of Advanced Study, Durham University

•

Notes:

St Cuthbert

Cuthbert was an Anglo Saxon monk, bishop and hermit who became prior of Lindisfarne in c. 665. In later life Cuthbert felt called to be a hermit and moved to the nearby island of Inner Farne to begin fighting the spiritual forces of evil in solitude.

Cuthbert became associated with the birds and other animals on the island and gave special protection to the Eider duck which is still known locally as Cuddy’s duck.

Reviews:

A Closer Listen (UK):

A Closer Listen’s Best Field Recording & Soundscape Albums of the Decade

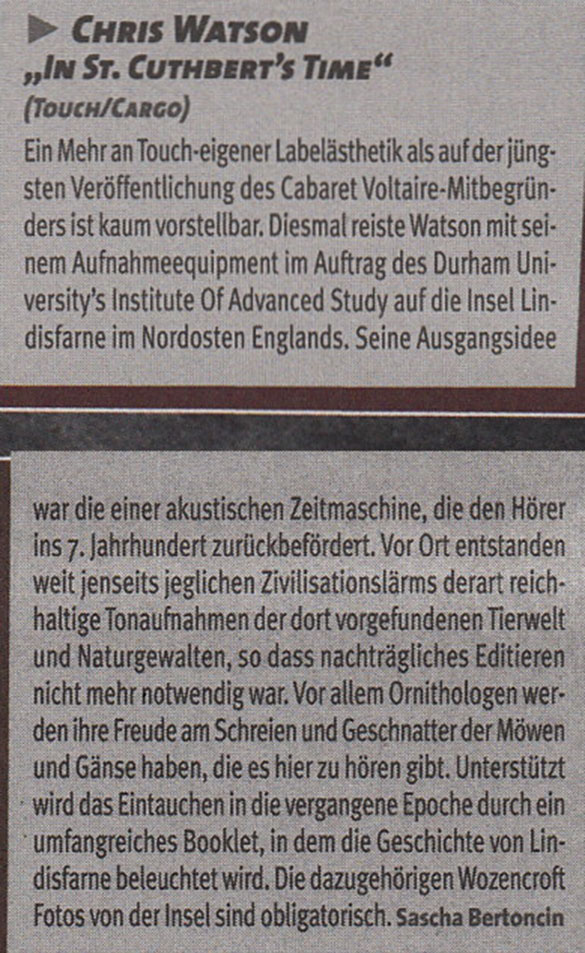

Chris Watson is best known as a wildlife recorder: if you want to hear lions devouring their prey from inside the carcass, or the sound of a whale breaking the ice at the pole, he’s the man to ask. He’s also presented Radio 4’s Tweet of the Day programme, which shares recordings of mainly British birds for early risers. Birds feature a lot on In Saint Cuthbert’s Time, too, which is an attempt to capture a 7th Century Soundscape of Lindisfarne, or Holy Island. As much of Watson’s work is to accurately capture the sounds of a location, this album presents something of a departure for him: to skip back some 1,200 years by ignoring the noise of people, boats and cars, and focus on the wildlife with the occasion sound emitting from the monastery. That ‘ignoring’ bit is no small task, and it must have taken Watson many hours to record and piece together the resulting album. Split into four tracks, one for each season, the listener can treat it as a virtual time machine, and let the imagination conjure the scenes of monks, seals and waves; or you can delve into the accompanying booklet and read about the island and its history from scholars at Durham University. Either way, In Saint Cuthbert’s Time is a brilliant, rewarding listen. [Jeremy Bye]

Drowned in Sound (UK):

It’s time to zone out in the ether once again, and gracefully gliding us into the realm of textural sound this month is former Cabaret Voltaire man turned award winning nature sound recordist Chris Watson. His latest record, In St Cuthbert’s Time, celebrates the current displaying of the Lindisfarne Gospels on Durham’s Palace Green by attempting to create an authentic sonic document of the Holy Island as it was when St Cuthbert arrived in 700AD. Of course we shall never be able to know quite how accurate Watson’s attempt is but there’s something about what is on offer here that manages to transport the listener to a world without the constant hum of modern technology. As impressively seamless as all his field recording works, the chatter of birds makes for the most memorable array of sounds present, but the whole mix is crucial to becoming fully encased by the album. Full immersion is like lying on the beach in the early hours with the wet sand stuck to your back and the sky breaking slowly into light, just as St Cuthbert himself might once have done. [Benjamin Bland]

You can read about it in the Newcastle Journal here, and Living North here.

The Wire (UK):

The island of Lindisfarne, just off England’s Northumberland coast, was once the home of an order of Irish monks, who settled there in the seventh century and so gave the small place the monikor of the Holy Island, a name that has stuck today. It is renowned for the Lindisfarne Gospels, reputedly written by Eadrith, one of the monastery’s bishops, and for St. Cuthbert, one of the monks that formed part of the settlement but who went on to be associated with the rich and diverse array of bird and animal life on the island, and in particular the Eider duck, found frequently on Lindisfarne and known locally as Cuddy’s duck. In 2013, to coincide with an exhibition of the gospels, Durham University awarded field recordist Chris Watson a research grant to explore the sonic properties of the island, and in particular to try and recreate sounds as they may have been heard there back in the seventh century. Watson visited the island at various points along the Anglo-Saxon calendar that the monks would have observed, producing the four seasonal works included here.

The recordings are beautifully made, immaculately captured and framed. On the whole they seek out the wildlife of the island, and there are no remnants of human activity anywhere to be heard on the album [not true – ed.]. So we hear the chatter of ducks and wading birds in winter, with a deep moaning tone in the background, formed from the persistent tidal surf hitting nearby shores. Starlings flock over the wind hissing through reeds during the Saxon season of haerfest (autumn) and a never-ending array of other birdlife, each accompanied by the sound of the natural environment inhabit the album. Watson has done a fine job of capturing Lindisfarne’s wildlife and nothing but. As a work designed to present to us what St Cuthbert and his cohorts might have experienced, it works exceptionally well. We feel transported to the place, a shift made all the easier by Maggie Watson’s stunning photography included in the album’s booklet. Watson has not sought to create music, but to produce an accurate aural artefact. Similar to how an archaeologist might work to rebuild an image of history through the research of remains, this recording attempts to recreate a moment in history, and on the whole has done it so very successfully. [Richard Pinnell]

Ondarock (Italy):

Chris Watson – indiscusso maestro della non-music per antonomasia – ha ancora voglia di stupire, ma soprattutto non vuol proprio saperne di appendere il suo microfono al chiodo. Dal treno fantasma alle rovine della famosa abbazia medievale di Lindisfarne, fondata da Sant Aidan nel 635 d.c. e principale fulcro dell’evangelizzazione britannica. Dagli industrialoidi e virulenti field-recording della linea ferrata messicana ai naturalistici suoni di campo della “Holy Island” inglese.

Per celebrare la mostra dei vangeli del 700 d.c. – da luglio a settembre 2013 – custoditi oggi all’interno della cattedrale di Durham, il nostro ex-esponente di Cabaret Voltaire e Halfer Trio, recandosi a Lindisfarne, rievoca i soundscape di quel periodo oscuro e violento, così come (forse) li percepiva St. Cuthbert di Northumbria nelle sue lunghe giornate da monaco eremita, prima che orde di vichinghi giungessero nella santa isola nel 793 d.C, devastandola.

È chiaramente un azzardo, nessuno può sapere che suoni ci fossero in quei luoghi e in quel dato momento storico, ma vogliamo credere che il signor Watson sia riuscito nell’impresa.

Sembrerebbe facile scrivere poche righe quando si tratta di field-recording a carattere ambientale. Ognuno con le proprie conoscenze naturalistiche può farlo e può sbizzarrirsi. Le domande da farsi piuttosto sono: sono tutti inseriti al posto giusto? Sono ottimamente curati? Rispecchiano fedelmente la realtà – da intendere senza uso di manipolazioni esterne?

La risposta è sì, anche se, a dirla tutta, suonano tristemente moderni. D’altronde, però, la Touch è un’autorità riconosciuta a livello mondiale, è una garanzia e Chris Watson è il suo profeta.

Per cui troveremo un vociare isterico d’oche, amabili cinguettii d’uccellini (probabilmente gabbiani del mare del Nord), e lo starnazzare impazzito d’anatre. Nebbia salina e minuscole gocce di pioggia si adagiano dolcemente sul fogliame autunnale/invernale (“Winter”), si mescolano alle gelide folate di vento, che, percorrendo il breve lembo di terra sabbioso che collega l’isola alla terraferma, in un attimo vengono rilasciate sulle verdi distese erbose come fossero lacrime di rugiada marina.

Non sono da meno le onde di mare, le quali pacatamente s’infrangono sulle piccole scogliere rocciose che sorreggono la collinetta, sulla cui sommità sorge il suggestivo e imponente castello.

Non stonano neppure i brevi intermezzi/inserimenti di campanellini, conferendo sensi di pace, quiete e rilassatezza. Tutto questo, poi, è accentuato nella traccia finale “Haefest”, laddove – accompagnati da molta fantasia – si riescono perfino a sentire inquietanti ululati notturni.

Al contrario d’altre etichette di musica cosiddetta sperimentale – come ad esempio l’austriaca Mego, sempre povera negli artwork – la Touch offre quest’immaginario sonoro dei tempi bui, accompagnandolo con ben 24 pagine di booklet. Una piccola precauzione: per una totale immedesimazione dei sopraccitati luoghi, “The Sounds Of Lindisfarne” va assolutamente gustato tramite una super-ermetica cuffia sonora.

Other Music (USA):

Field recordings appear to be having a moment in the spotlight, and in recent years the genre has affected contemporary art circles as well, notably taking a prominent role in MoMA’s upcoming large-scale sound exhibition, Soundings: A Contemporary Score. There have also been ongoing exchanges with more popular strains of music, not in the least through the well-known work of Other Music favorites Boards of Canada, or the phonographic interludes on Julia Holter’s avant chamber pop debut Tragedy. Given these continually developing trends and hybrid approaches, it remains inspiring to hear how the genre is explored in its purest form on each new release by British “sound recordist” Chris Watson. Using the microphone as an instrument to reveal sounds habitually unheard by humans, his recordings contain an almost unreal ability to place the listener directly within the environment that is being registered. On In St. Cuthbert’s Time, Watson sets forth to explore the sonic properties of Lindisfarne, a scenic island off the coast of Northeast England, with a rich history that encompasses both Vikings and Sir Walter Scott, as well as Roman Polanski, who shot his 1966 film Cul de Sac on location there. The recordings are an attempt to provide an aural imprint of how Lindisfarne might have been experienced in 700 A.D. when St. Cutberth, a monk, bishop, and hermit, became associated with its wildlife. We hear chatter of ducks and wading birds in winter, and then go off on a series of recordings that reflect the quotidian and seasonal flows of the variety of sounds present on the island. The unidentifiable and unverifiable nature of many of these sources adds to the complexity of the listening experience. With an added level of historical and scholarly frameworks that made this project possible, and stunning photography included in the CD booklet, this work is a triumph in both its exactness and strangeness, straddling nature’s complex sonic landscape and the uncanny effect of these sounds when registered through a microphone. [NVT]

Decoder (USA):

A small island measuring just over a mile across and two miles in length, Lindisfarne sits just two miles off the coast of Northumberland and something like 200 people call it home. Known colloquially as Holy Island, Lindisfarne is thought to have been populated as long ago as the 7th Century, when King Oswald invited monks down from Scotland to establish a monastery there. Cuthbert – monk, hermit and later saint – became the priory’s abbot and much revered until his death in 687, by which time he had retired to a smaller island and lived completely alone. In case you are interested, Cuthbert’s miracles include remaining “as flexible as a living man” for centuries after his death and continuing in such a state as to allegedly frighten Henry VIII’s church-wreckers into leaving Durham Cathedral during the Reformation.

Worshippers used Lindisfarne priory for almost 700 years, withstanding successive Viking raids and – if the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is to be believed –- “whirlwinds, lightning, and fiery dragons.” The monks eventually left the island in 875, taking the body of St. Cuthbert with them (no records exist that state he ran alongside) and reburying him in Durham, but not before they could produce one of England’s greatest treasures in the Lindisfarne Gospels and, in particular, the St. Cuthbert Gospel, both of which now reside in the British Library.

Holy Island these days is accessible sporadically by road, but only when the tide recedes far enough to allow cars across. It is one of the most exciting trips a child from the UK can take, and I remember it vividly myself. In the back of my dad’s Volvo, faces squashed against the windows and the salty smell of sea in our nostrils, my sister and I looked out for seals and puffins, all the while slightly nervous the sea would have an abrupt change of heart and come washing back in to trap us. The dogs were sick in the boot, causing my dad to threaten them with exile halfway there and my sister to throw up in response. It was a great day out – not because of the history (boring!) or the shops full of mead (looking back this was a major oversight on my part), but simply because we were driving across the sea in a car. The priory’s ruins still remain, and many Anglo-Saxon relics are dotted right across the island. There is a castle there too, sat relatively solidly atop the cliffs due to an extensive renovation in 1902. The atmosphere can be strange, at once remote and bustling, and the town has taken full advantage of the tourists, offering everything from shells with your name painted on to miniature stained glass windows showing St. Cuthbert and his beloved ducks. Further away from the centre it is easier to imagine what the island must have been like in the 7th Century. Grey seals, a million birds and the sounds and smells of the crashing North Sea come together to create a feeling of true isolation; closing your eyes here and sitting in the grass can provide a genuinely spiritual experience.

If there is anyone working today who is qualified to capture this sensation it is Chris Watson, a founding member of Sheffield’s industrial music pioneers Cabaret Voltaire and currently a wildlife sound recordist for the BBC. His new album for Touch, In St. Cuthbert’s Time, was recorded entirely on Lindisfarne in honour of “that period of exceptional thought and creativity” in which Cuthbert and Eadfrith (the creator of the gospels, often considered the saint himself) were establishing religion on the island and the return of the original manuscripts to Durham Cathedral for exhibition this year. Made up of four roughly quarter-hour pieces, In St. Cuthbert’s Time eschews human interaction almost completely and focuses on the ebb and flow of the four seasons, named here in Anglo-Saxon. “Winter” is accordingly gusty, based mainly on the island’s rugged coastline; “Lencten” (or Spring) moves slightly inland and is relatively calm; “Sumor” (Summer) is busy with insects, and so on. The recordings are presented “straight” – that is to say they have not been manipulated in any way or subjected to any kind of sonic wizardry except for the editing. They are, therefore, remarkably immediate, dreamily captivating and wholly transporting.

“Winter,” the most dramatic of the four pieces, is battered constantly by the wind and rain as huge numbers of different sea birds fly overhead and gather on rocks. You hear their wings flapping, and their calls, screams and hoots both distant and right alongside the recording equipment. Any ornithologist worth his or her salt would no doubt pinpoint every single one of them (more than 300 species have been counted there over the years), but part of the experience for me was not having a clue what creature I was hearing. Some of the cries are unnerving: from somewhere deep inside the cold waves of “Winter” emerges a quite terrifying screaming sound – the Vikings, perhaps, landing to wreak havoc – but continued exposure reveals it to be avian after all. “Lencten” opens with the eider duck’s bizarre call; sounding repeatedly surprised, the ‘oohs’ they give out are more like those from a girl whose lover insists on unexpectedly grabbing her backside in public than a bird.

In St. Cuthbert’s Time is as “authentic” an experience as you want to make it, and you’ve got to think it will probably work better if you’ve actually had the pleasure of visiting the island or somewhere like it. You can imagine the CDs lined up for sale in the cathedral shop for punters who’ve ogled the Gospels but you can’t necessarily imagine the same people spinning the album at home. Watson recently talked to a Durham newspaper about his time on Lindisfarne and the installation at the cathedral. “What’s really interesting [about the island] is what’s not there now,” he said. “They’ve found a lot of bones there [including those of] the Great Auk. Obviously I don’t have a recording of that because it’s extinct.” This brings about all kinds of questions about the value of these field recordings beyond their use in art. “Sumor,” for example, features the distinctive call of the cuckoo, an increasingly rare sound in the UK and one that Watson was encouraged to seek out due to it being mentioned in text from around the time of Lindisfarne’s colonization. The Gospels, in fact, are packed with illustrations of wildlife, which Watson puts down to the close proximity in which Eadfrith must have lived alongside the birds, and legend has it that Cuthbert got so friendly with the eider ducks that they nested in his bed. So while we can wonder eternally about whether In St. Cuthbert’s Time provides a true reflection of how the island might have sounded in the 7th Century, we can say for certain it performs well as a sonic record of its wildlife for future generations.

For me the album is at its most convincing during the relative quiet of “Sumor” and “Haefest” but then these are the pieces I most naturally identify with having been brought up on a farm. They are gentler journeys, with a lapping sea and the hungry chatter of growing chicks born during “Lencten.” There is a steady shift inland which sees the breeze unveil the hum of flies, the twitter of field birds in the grass, and the burly low of cattle in the distance. I can recognise the scene almost straight away, and it is an idyllic one. You can practically feel the sun on your back and see the dazzle of buttercups along the ground; the frantic winter world of the cliff edges and rock pools seems a million miles away.

Whereas previous Chris Watson recordings for Touch have traded in subtle psychological horror (El Tren Fantasma), brooding intensity (Storm, with BJ Nilsen) and Gothicism (Stepping Into The Dark), In St. Cuthbert’s Time is somehow harder to pin down. It is certainly his most pedestrian set of recordings yet, which is not to say it is dull, but its success almost certainly depends on how much time and imagination you are willing to invest. For those without access to Holy Island, an extensive knowledge of 7th Century Britain or the exhibition in Durham Cathedral, that might be harder than you expect. [Steve Dewhurst]

A Closer Listen (USA):

We usually recommend the physical copy due to its specific beauty, but in this case, we do so because of the liner notes. Students of history, tradition, and religion will cherish the efforts made by the authors to place this release in context. The 24-page booklet is both educational and entertaining, making In St. Cuthbert’s Time a complete multi-media work.

Here’s the short version: on this album, sound artist Chris Watson attempts to reflect the environment experienced by the monks of the Holy Island (two miles of the coast of Northumberland) in 700 A.D. The sea, the birds and the iron prayer bells worked their way into the margins of the Lindisfarne Gospels, while influencing the spiritual life of the island’s faithful. Their closeness with nature can barely be imagined today, as modern humans tend to retreat from nature save for occasional forays to the mountains or beach. The livelihood of the monks was tied to their immediate surroundings: grain and fruit, farm animals and fish. A good year meant a good harvest, but drought could decimate a community. In the eyes of the monks, God would provide or He would not; and they trusted in His care.

While Watson could not, for obvious reasons, duplicate the island’s medieval soundscape, In St. Cuthbert’s Time bears the sounds of avian descendants. Many of the same species still occupy the island: still migrate, still return. By dividing his recording into four parts, one for each season, Watson is able to position each sound in its proper place. ”Winter” is marked by geese, ducks, and swans, “Lencten” (Spring) by skylarks, plovers and snipe. The Eider duck (later renamed Cuddy’s duck), featured prominently in “Lencten”, possesses a particularly human-like mating cry: ”Aooo! Wooo!”, as far from a quack as one can imagine. A few subjects seem close enough to eat Watson’s microphone. The drumming of the snipe is also memorable, an arpeggio of airborne notes. We recommend this creature to Flaming Pines as a possible subject for a Birds of a Feather disc.

As “Sumor” approaches, the sounds of linnet and cuckoo are joined by those of insects and cattle, as the waves continue to lap all around. Angry terns defend their nest, and boy, do they sound mad. (If you’ve never experienced this, we have one piece of advice: wear a hat). Children who are listening will enjoy the cuckoos and cows, since they’re easy to identify. Additional points are awarded to any who can identify the yellowhammer at first cry. Finally comes “Haerfest”, with deer stags and grey seals, the latter a familiar subject for Watson. As the waves crash, the listener is reminded that the monks were isolated from the mainland by a fierce sea. The year is done, the cycle begins anew.

No planes are heard on the recording. These must have been hard to avoid, but the legitimacy of the soundscape would have been ruined had they been included. With many soundscapers bemoaning the lack of pure sonic environments, Watson’s disc is proof that one can still be captured: all it takes is the patience of a saint. The monks are honored by this respectful recreation. [Richard Allen]

African Paper (Germany):

In den meisten Fällen ist ja doch von Musik die Rede, wenn der Begriff “field recordings” fällt, von Klängen also, die zwischen Aufnahme und Mastering einige bedeutsame Bearbeitungsschritte erfahren haben, was nicht selten in unterschiedlichen Graden der Verdichtung, Harmonisierung oder Rhythmisierung resultiert. Die eigentlichen Feldaufnahmen sind in dem Fall nur ein Moment unter vielen. Chris Watson, der allein in seiner Zeit bei The Hafler Trio sein Können im oben genannten Bereich ausgiebig demonstrierten konnte, ruft in seinem neuen Release nicht nur das Rohmaterial selbst in Erinnerung, sondern auch den Ursprung des Begriffs in der Welt der Wissenschaft, entstand die “Feld”-Metapher doch in Anlehnung an die soziologische Praxis der Feldforschung. Musik findet sich auf seinem neuen Album keine, auch wenn das Wort „Gospels“ im Titel das vielleicht suggerieren mag.

Mit Soziologie hat Watsons neuestes Projekt allenfalls am Rande zu tun, vielmehr ging es in dem von der Durham University finanzierten Auftrag darum, die klangliche Atmosphäre der nordenglischen Insel Lindisfarne möglichst in Abwesenheit zivilisatorischer Klangquellen aufzunehmen und zu dokumentieren. Lindisfarne, das so nahe an der Küste gelegen ist, dass man es bei Ebbe auch per Auto erreichen kann, ist ein für die Geschichte Großbritanniens wichtiger Ort. Im 7. Jh. ließen sich dort schottische Mönche nieder, primär in der Absicht, von dort aus den nicht keltisch geprägten und aus christlicher Perspektive rückständigen Teil der Britischen Inseln zu missionieren. Bald entstand auf der „Holy Island“ das zeitweise wichtigste Kloster dieser Bewegung, die unabhängig und z.T. im offenen Widerspruch zu Rom agierte und erst gut zwei Jahrhunderter später durch Wikingerüberfälle zuende ging. Das wichtigste bis heute erhaltene Erzeugnis aus dieser Zeit sind die Lindisfarne Gospels, eine pergamentene Evangelien-Ausgabe von beeindruckender künstlerischer Virtuosität. Über all dies kann man sich in dem aufwendigen Booklet informieren, das auch optisch – Stichwort Jon Wostencroft – den bekannten Touch-Standards entspricht.

Vom Kloster der frühen Missionare sind heute nur noch Ruinen erhalten, ebenso von der späteren Benediktinerabtei und der in der Neuzeit errichteten Wehrburg. Dass die Insel heute primär Vogelschutzgebiet ist, fällt bei den Aufnahmen, die jeweils eine Jahreszeit dokumentieren, am deutlichsten ins Auge, denn neben der Brandung und den Geräuschen von Wind und Regen sind vor allem Vögel zu hören – ihre Stimmen, ihre Bewegungen in Luft und Wasser. Monoton und eindimensional ist das keinesfalls: Im „Winter“-Teil hat das Schnattern der Gänse und Enten einen fast rhythmischen Charakter, so dass man für Momente an der fehlenden Bearbeitung zweifeln mag, das An- und Abschwellen ihrer Stimmen über dem konstanten Dröhnen der Brandung erfolgt zwar in Intervallen, die allerdings sind in Länge, Dichte und Klangfarbe stets unberechenbar. In den weiteren Jahreszeiten „Lencten“, „Sumor“ und „Haerfest“ kommen weitere Vogelarten hinzu, Schwalben, Möwen und etliche mehr, die im Booklet akribisch aufgeführt sind, und es muss Spaß machen, dies alles auseinanderhalten zu können. Der Frühling mit seinem helleren, luftigeren Klang und seinen sanften Wellen klingt insgesamt maritimer, im Sommer gerät die Brandung zu wahrem Lärm und im Winter gesellen sich Robben hinzu. Unerklärlich das Klingeln (von einem Schiff?) und die gruseligen Tierstimmen im zweiten Teil, die sich wie menschliche Stimmen anhören.

Natürlich werden einige monieren, dass auf der CD „nur“ Vogelstimmen und andere Naturgeräusche zu hören sind und behaupten, die Idee sei besser als das Resultat. Aber das wäre nur ein Indiz für Desinteresse, denn das Resultat lebt von der Idee, und beansprucht keineswegs zur Hintergrundbeschallung gehört zu werden. Watson dokumentiert die Klänge einer Insel, wie sie vor der Ankunft der ersten Mönche geklungen haben mag und wie sie auch heute wieder klingt, ohne Gebete, Gesänge und Glocken. Wer hat nun den Sieg davon getragen, die christliche Religion oder die ewigen Rhythmen des Jahres und der Gezeiten? Bedenkt man die beeindruckenden Ruinen und die Seiten der Lindisfarne Gospels, dann sollte klar werden, dass dies keine Frage von entweder/oder ist. [U.S.]

VITAL (Netherlands):

Sometime in the 7th century, Eadfrith, the Bishop of Lindisfarne, was writing and illustrating the Lindisfarne Gospels on the island of that very name and maybe he heard what we hear now. No doubt his work was slow, all year round, and so the four pieces created here by Chris Watson, reflect the four seasons. The island is to be found two miles of the coast of Northumberland. If you already know Watson’s work, and there is no reason why you shouldn’t, then you know what to expect here. Lots of wind, birds, insects and water sounds. It’s a fine work, totally Watson’s standard, and it comes with a great informative booklet on the place and the historical information, but it’s not the same kind of work as ‘El Tren Fantasma’, which I believe to be one of the best works by Watson in recent years. Maybe because that piece was different from the works of Watson as we knew them, away from the nature recordings and working with mechanical sounds, whereas this one is back to nature recordings. Of course, I know, there is no reason to complain as this is of course the kind of thing he is best known for, and ‘In St. Cuthbert’s Time’ is a very refined work of such recordings, being put together into some great pieces of music. Let there be no mistake: this is great album. With doors open on this sunny afternoon, in my quiet neighborhood, this is a record that is truly an ambient record. Great. [FdW]

The National (USA):

Seventh-century sounds comprise intriguing new album

Chris Watson has made an intriguingly alien-sounding album with a series of purposefully earthbound sounds. The sources of the sounds couldn’t be more plain: wind and water, bugs and birds, scatterings of animate and inanimate subjects and objects all around. They’re so plain, in fact, that they permit the album’s peculiar premise: to summon the state of the world as it would have sounded more than 1,300 years ago.

There’s little archaeological evidence to suggest the existence of microphones in the north of England in the 7th century, but other than that, nothing at work sound-wise on Watson’s new album In St Cuthbert’s Time would have been out of place way back when. Great efforts were made to be faithful to the place under consideration, namely the English isle of Lindisfarne, owing to its significance as the home of a monastery where a manuscript was made by monks in tribute to St Cuthbert, a medieval Christian saint whose memory has been ferried through time.

The illuminated manuscript, known as the Lindisfarne Gospels, was especially grand and ornate, and whatever its religious worth, it remains a strikingly beautiful relic from a time when the act of making even a simple book meant months of toil and painstaking work by hand. Pages were made of vellum, a form of parchment produced from the skin of calves, and inks and materials for binding weren’t exactly waiting around to be purchased at the corner shop.

The elements, too, wreaked havoc on work sometimes done in less than cosy shelter. In the liner notes to In St Cuthbert’s Time, a quotation reads: “The conditions of the past winter have oppressed the island of our race very horribly with cold and ice and long and widespread storms of wind and rain, so that the hand of the scribe was hindered from producing a great number of books.”

The natural world, then, was a principal player in pretty much everything that could have possibly transpired at the time, and the natural world is what makes up the bulk of the sound world brought into focus by the recordings captured by Watson with nothing more than some microphone equipment and a pair of curious ears. Watson first developed his ears in a notably different realm: as a founding member of the spectacularly strange 1970s post-punk band Cabaret Voltaire. (Early use of electronic rhythms and sounds figured into such Cabaret Voltaire classics as Do the Mussolini (Headkick) and Nag Nag Nag.) More recent years, however, have been devoted to the practice of field-recording, or making recordings out in the field, in places all over the globe. A past album of his, Weather Report, features the high-fidelity sounds of cracking and creaking from a gigantic glacier in Iceland; another, El Tren Fantasma, tells the sonic story of a cross-country journey on a Mexican train. For In St Cuthbert’s Time, he recorded the isle of Lindisfarne as it would have sounded during the era of that idiosyncratic saint, who in his spiritually searching solitude was thought to have developed special bonds with the wildlife in his surroundings. (“Birds and beasts came at his call,” the story goes.)

The album, then, is just that: recordings of ambient existence outside on the island, edited into four long tracks by the seasons and otherwise presented unadorned. It’s a magnificent aesthetic achievement and also, by a different measure, not even remotely an aesthetic achievement at all. [Andy Battaglia]

Sonic Seducer (Germany):

Spex (Germany):

New Music (Poland):

www.nowamuzyka.pl/2013/08/11/chris-watson-in-st-cuthberts-time/

Ambientblog (net):

Brainwashed (USA):

A distinctly different release than his last, El Tren Fantasma, this album not only acts as part of an overall larger project (a collaboration with faculty at Durham University), but also focuses on nature, rather than that disc’s use of man made transportation. Not just nature, but an attempt to capture the essence of of Lindisfarne Island as it would have sounded to St. Cuthbert in 700 AD. The result is an album that is a bit less compositionally oriented than El Tren Fantasma, but one that does an impeccable job at capturing a feel and an environment via audio.

This disc is part of an exhibition of the Lindisfarne Gospels in England, and is intended to provide an audial context for the environment in which Eadfrith, the Bishop of Lindisfarne, was writing and illustrating the gospels that are being exhibited. Even disconnected from this context, the album is another example of Watson’s unparalleled ability at capturing sound in a completely engrossing manner.

The album is broken up into four separate pieces, each titled for the season in which they were recorded. The vibrancy and activity of the recordings is closely tied to the time captured: the droning wind and infrequent bird calls of “Winter” are so much more cold and isolated than the aggressive avian flocks that permeate “Sumor.”

Appropriately, both “Lencten” (“Spring”) and “Haerfest” (“Autumn”) sit somewhere between these two extremes in fauna and activity. The former captures the almost human like calls of land and water birds amidst a greater sense of life and vibrancy in comparison to the preceding piece. “Haerfest” channels the bleakness of oncoming winter in its more muffled, darker sound. Gaggles of birds can be heard, likely migrating away to warmer climates while the vocalizations of seals and deer bring a bleaker, foreboding sense of the cold to come.

Surely the changes of climate have changed the environment that is the island of Lindisfarne from its medieval days, but Watson’s recordings sound completely timeless, largely devoid of any human presence to solidify the isolation the Bishop experienced while completing the gospels. In fact, the only hint of humanity is the simple ringing of a hand bell towards the end of each piece, representing a call to prayer that would have been heard over 1300 years ago.

Watson’s work definitely would make for an ideal accompaniment to the exhibition of the Lindisfarne Gospels, but even removed from that context it is a captivating, and beautifully captured disc of field recordings. It seems to be less of a composed work than some of Watson’s other output, but even just a raw capturing of the environment makes for an amazing work. Again, there does not seem to be an environment that Watson cannot distill to its most fascinating sonic elements. [Creaig Dunton]

Caught by the River (UK):

To celebrate the exhibition of the Lindisfarne Gospels on Palace Green, Durham from July to September 2013, award–winning wildlife sound recordist Chris Watson has researched the sonic environment of the Holy Island as it might have been experienced by St Cuthbert in 700 A.D.

Picture the scene. 7th Century Britain. A windswept and sea-battered island sitting two miles off the coast of Northumberland. Inhabited by a group of monks who had dedicated their lives to the word of God. Within the holy walls of the priory a bent figure patiently creates one of the greatest religious treasures in the history of British Christianity – the Lindisfarne Gospels.

Eadfrith, Bishop of Lindisfarne from 698-722 was the monk responsible for this remarkable illuminated manuscript. A note added to the end of the Gospels states that this was written for “God and St Cuthbert”, a former bishop of Lindisfarne. Both men seem to have been incredibly influenced by the natural sounds that surrounded them. While in self-imposed exile on the nearby Farne Islands, St Cuthbert introduced laws of protection for the local seabirds there, particularly the Eider Duck (affectionately known as Cuddy’s Ducks in Northumberland). Eadfrith too drew inspiration from natural history, incorporating stylised images of the birds he observed on Lindisfarne into the pages of the Gospels. I think it’s safe to say that both men would have drawn some additional spiritual sustenance from their wild landscapes – they were monks after all so spirituality wouldn’t have been in short supply. But many people, even to this day, have found great inspiration in the sights and sounds of the natural world; while labouring over the Gospels, Eadfrith would surely have experienced the same.

Equally inspired by the sounds of Lindisfarne and the story of this significant period of sacred creativity, wildlife sound recordist extraordinaire Chris Watson set about recreating the soundscapes that would have tickled the ears of those living and working on Lindisfarne during the 7th Century.

Modern day listeners are treated to four composed soundscapes that incorporate the songs and calls of animals that have existed on the island for millennia. Water and wind are also constant elements, reminding us of the wild topography of this ancient land. Each track is based on a season and so we move through the sounds of winter (winter), spring (lencten), summer (sumor) and autumn (haerfest). A plethora of species are encountered over the course of the year. Winter brings us the sounds of Wigeon, Oystercatchers, Brent Geese, Whooper Swans, the wingbeats of Greylag Geese passing overhead and a bubbling Curlew. With spring we hear Redshank, Black-headed Gulls, a drumming Snipe, the shimmering song of a Skylark in full flight and of course the gentle cooing of Cuddy’s Ducks (Listen closely – don’t you think they sound a little like Frankie Howard?). The sounds of summer are equally strident, with the cackling cries of Arctic Terns defending their nest sites, a Buzzard circling overhead and a group of calling Herring Gulls. Moving away from the shore we hear the songs of Swallows, Yellowhammers, House Martins and a Cuckoo being swept across the island by the unrelenting wind. The mooing of gentle cattle signifies both a source of nourishment for the monastic community and vellum for Eadfrith’s legacy. And finally to autumn where wading birds dominate the scene. The roars of Red Deer stags drift over the land and, as the tide turns, these are replaced with the haunting cries of Grey Seals. The sound of a monk’s bell draws to a close each soundscape; a thoughtful touch that subtly reinforces the connection between the island’s wildlife and religious inhabitants.

As you’d expect, the skill and attention to detail in putting these pieces together is of the highest calibre. If Eadfrith or St Cuthbert were able to hear ‘In St Cuthbert’s Time’ would they recognise the familiar soundscapes of the land that meant so much to them? You bet they would. Chris has created a work that is enjoyable to listen to, highly evocative and steeped in history. You’ll love what you hear and learn a thing or two as well. What more could you ask for? [Cheryl Tipp]

Debug (Germany):

Headphone Commute (UK):

Why do I keep returning to field recordings by Chris Watson? I suppose the answer is similar to the reason behind watching visually stunning BBC documentaries like Planet Earth and Blue Planet. And just as I chase the higher definition quality of those shows, so do I rely on this award-winning wildlife sound recordist to deliver the highest production quality archive of a particular sonic environment. In the case of his latest release on Touch, entitled In St Cuthbert’s Time, there is an associated concept that plays a key role in this aural piece of captured time and place. Watson subtitles this four-track hour-long release as “The Sounds of Lindisfarne and the Gospels”. And before diving deeper, we shall allow Watson to explain: “Throughout human history artists have been influenced by their surroundings and the sounds of the landscape they inhabit. When Eadfrith, the Bishop of Lindisfarne, was writing and illustrating the Lindisfarne Gospels on that island during the late 7th C. and early 8th C. he would have been immersed in the sounds of Holy Island whilst he created this remarkable work. This production aims to reflect upon the daily and seasonal aspects of the evolving variety of ambient sounds that accompanied life and work during that period of exceptional thought and creativity.” On the surface of the record, there is nothing more than the sounds of wildlife, dominated by birds, insects, and occasional reptiles. The habitat’s weather adds a backdrop to each piece, making the sound cold, dark or humid. But dig further, and the meditative state of the album opens up, placing one into an exotic climate, exploring its depths and mysterious secrets. And when each phonic snapshot concludes, I realize that I’m back in my [head] space, warm, sterile and dry. And so I hit play again.

Rifraf (Belgium):

Thumped (UK):

Chris Watson’s recordings from Lindisfarne Island form “an imagined historical document, an abstract and fictional manifestation of what a particular place might have sounded like at a particular time”.

Awooo! Wooo! Awoooo! Woo!

Eider ducks are strange sounding creatures, almost human in their low, questioning cries. They were apparently loved and afforded special protection by Eadfrith, an early Christian bishop who lived on Lindisfarne island around the turn of the 8th century. Eadfrith, later known as St. Cuthbert, was there to pray, seek God and work on the beautiful manuscript that is the Lindisfarne Gospels. In St Cuthbert’s Time sets out to recreate the soundscape of Lindisfarne island as it existed at that time. The recordings have a two-fold purpose, first as a surround-sound installation inside Durham Cathedral’s Holy Cross Chapel and second as an album released by Touch.

Watson presents his recordings as four separate seasons, beginning in Winter and cycling forward through the year. The Eider ducks make their appearance in ‘Lechten’ (Spring), their unmistakable calls rendered beautifully by Watson’s recording, seemingly close enough to touch.

Obskure (France):

freq.org.uk (UK):

If you have ever scanned the technical credits of television programmes as they glide slowly past in the wake of the action, chances are you will have seen the names of either Ken Morse or Chris Watson, or both. Morse is sometimes reckoned to be the most credited cameraman in history, so often have his rostrum camera skills contributed to the jewels that fall from the small screen. Watson’s incredible close-mic sound work, similarly, has appeared across a staggering continuum of radio and television broadcasting, particularly in arena of natural sound, from Bill Oddie’s Springwatch to David Attenborough’s The Life of Birds. Truly Watson has an embarrassment of riches: generally regarded as one of the most gifted and creative sound recordists in the business, not only are his wildlife recordings techniques without peer, but Bill Oddie also says of him “I don’t know anyone who is so intense yet so splendidly frivolous.” The moral of the story is that whatever you need, be it the evening call of a Red Rumped Tinkerbird or the crashing fluke of an amorous Right Whale, Watson is your man.

Be it the evening call of a Red Rumped Tinkerbird or the crashing fluke of an amorous Right Whale, Watson is your manYet before this illustrious career began (back at Tyne Tees Television in the early 1980s), Watson was also a founder member of Cabaret Voltaire, Sheffield’s legendary sound collagist industrial pioneers. He was also a prime mover in the establishment of conceptual sound artists The Hafler Trio. Impressed yet? For one CV to encompass both the Cab’s awesome “Nag Nag Nag” single AND a BAFTA for Best Factual Sound, and to have supported both Ian Curtis AND a former Goodie, shows a breadth of experience and output to which no one person should have a right. Only the fact that Ken Morse was embedded with The Magic Band in Woodland Hills, filming their claustrophobic eight-month rehearsal odyssey for Captain Beefheart’s Trout Mask Replica, keeps his credibility apace with Watson’s. Or I may have just made that last bit up.

However, as if that were not enough, Watson has also released a string of absorbing, intimate, oddball and completely idiosyncratic solo albums, beginning with 1996’s Stepping in the Dark, a compilation of sonorous atmos recordings ranging from the South American rainforest to Kenya’s Mara River to the Moray Firth in Scotland, and including 1998’s stunning Outside the Circle of Fire (featuring a stellar cast of cheetah, deer, capercaillie, kittiwake, spider monkey, nightjar) and 2011’s spooky El Tren Fantasma (a haunting soundscape documenting a train ride across Mexico, describing the passage from Los Mochis to Veracruz, coast to coast from Pacific to Atlantic).

Re-imagines the sonic environment of the Holy Island as it might have been experienced by Cuthbert, an Anglo-Saxon monk. Watson’s latest release, In St Cuthbert’s Time, originated as piece commissioned to celebrate the exhibition of the legendary Lindisfarne Gospels at Durham Cathedral in Summer 2013, and attempts to encapsulate the acoustic landscape that would have surrounded and influenced Eadfrith, the Bishop of Lindisfarne, during the time that he was writing and illustrating the Gospels. This utterly immersive soundscape re-imagines the sonic environment of the Holy Island as it might have been experienced by Cuthbert, an Anglo-Saxon monk who became prior of Lindisfarne, around 700AD.

Given Cuthbert’s particular association with the avifauna of the island (the eider duck was, apparently, one of his particular favourites, and who could quibble with that?), it is their fantastically rich and diverse sound environment that dominates the four Anglo-Saxon seasonally-themed recordings that comprise the album, underpinned by the movement of water, and play of the wind and the elements across the natural topography of the island. “Winter” (Winter) moves across a host of contributors including widgeon, oystercatchers, brent geese, whooper swans, greylag geese and a curlew that sounds as though Aphex Twin is running it through his mixer in a faintly angry mood. “Lencten” (Spring) brings us a changed cast including redshank, black-headed gulls, “a chorus of drumming snipe” (the avian equivalent of Charles Hayward), a Skylark and, of course, Cuthbert’s beloved eider ducks who turn out to sound spookily like a Carry On character reacting to a particularly fruity double entendre.

Starlings and cuckoo, counterpointed by the seasonal buzz of insects and the ruminant mooing of local bovines“Sumor” (Summer) buries us beneath a swell of arctic terns, linnet, whitethroats, yellowhammers, swallows, martins, starlings and cuckoo, counterpointed by the seasonal buzz of insects and the ruminant mooing of local bovines. (Said bovines would, of course, also have provided the vellum upon which the Lindisfarne Gospels would have been produced, so I guess they have something to moo about). “Harfest” (I’m giving up on this now) closes the suite, heavy with wading birds such as golden plovers, redshank, dunlin and knot, these gradually giving way in an imperceptible sonic pan first to the plaintiff throaty gargle of a red deer, and thence to the melancholy song of the grey seals resting nearby.

Each of the four pieces closes with the sound of a monk’s handbell, admirable rung by Martin Williams, and reminding us both of the presence of man within this fabulously intense natural environment, and of Eadfrith, toiling away on his illuminated manuscript within the stone walls of the priory.

The chance meeting of a goose and plover on a turn table… As with all of Watson’s work, although it comprises holistic acoustic landscapes, it is far from being ‘ambient’, some dull aural wallpaper designed to stick on unobtrusively in the background whilst attending to other matters. Indeed not. Instead, it is powerful blast of natural musique concrète intended to produce a spark from the chance meeting of a goose and plover on a turn table. One should best experience this bejewelled audio tapestry by lying back in the dark, donning a pair of fuck-off expensive Sennheiser headphones, and marvelling at Watson’s ability to both bring us right into the heart of the sounds of the natural world, and to reveal their strangeness and beauty to us. The truly awesome stereo movement of massed wingbeats in “Harfest” achieves the kind of show-stopping sonic intensity of which fêted (fœtid?) studio producers and abrasive avant-garde artists can only dream of. Not bad for a widgeon or two really.

Like St Cuthbert, I think I’ve developed rather a soft spot for the eider duck. [David Solomons]

Gonzo Circus (Belgium):

Black (Germany):

Die Fieldrecordings von Chris Watson (Ex-CABARET VOLTAIRE/THE HAFLER TRIO) begleiten mich ja nun schon einige Jahre und stets haben mich seine Arbeiten persönlich mehr berührt, als alle anderen inflationären Mitbewerber in diesem Genre. Gerade seine letzte CD „El Tren Fantasma“ war eine ungemein aufregende wie mitreißende Eisenbahnfahrt quer durch Mexiko, die jetzt förmlich im völligen geographischen Gegensatz zu seiner aktuellen Auftragsarbeit für die Durham University steht. Im eher unwirtlichen Klima der Nordostküste von England hat er diesmal nämlich die Audio-Atmosphäre der Lindisfarne-Insel im Wandel der Gezeiten eingefangen bzw. dokumentiert. Die Insel wird ja auch „Holy Island“ genannt und ist seit vielen Jahren ein Vogelschutzgebiet, nachdem in grauer Vorzeit von dort aus die Christianisierung Englands betrieben wurde. Nach Wikinger-Überfällen wurde das Kloster aber von den Mönchen aufgegeben und dessen herrliche Ruinen sind bis heute ein Wahrzeichen der Insel. Unterteilt in die Abschnitte Winter, Frühling, Sommer und Herbst lässt Chris Watson nun den Wind, die Wellen und vor allem Vögel für sich sprechen, was in seiner puren Konsequenz einfach nur beeindruckend und faszinierend ist! Mit unter hat das dominante Schnattern und die rauschende Brandung etwas bedrohliches an sich, wie der Gezeitenwechsel in seiner hörbaren Veränderung richtig spannend ist. Ein dickes Booklet rundet zum Abschluss die Veröffentlichung im Digipack ab, welches nicht mit Informationen und anschaulich illustrierenden Fotos zum Thema geizt. [Marco Fiebag]

Whisperin’ & Hollerin’ (UK):

Laif (Poland):

Revue et Corrigé (France):

Sentireascoltare (Italy):

Blow Up (Italy):

kindamuzik (Netherlands):

Dat Chris Watson een fiks aantal blauwe maandagen geleden lid was van het avant-gardistische collectief Cabaret Voltaire is niet meer te horen aan zijn recente releases. De man heeft zich buitengewoon verdienstelijk bekwaamd in de schone kunst van de field recording. Daarvan getuigt bijvoorbeeld de wonderlijke en intrigerende steppensymfonie Weather Report of zijn ‘compositie’ voor zwermen bijen. Op In St Cuthbert’s Time… waait een striemende kustwind waarop kwetterende meeuwen, eenden en andere vogels meedeinen; de branding rommelt en je hoort de ritseling van het her en der de kop op stekend helmgras.

Het eilandje Lindisfarne was vanaf de zevende eeuw gekoloniseerd door Ierse monniken. Daar werden de gelijknamige gospels opgetekend en leefde ook Sint Cuthbert. Hij verdiepte zich in de flora en fauna op het eiland. Dit jaar worden de geschriften tentoongesteld en ter gelegenheid van de expositie kreeg Watson de opdracht een werk te maken dat niet alleen de klank van Lindisfarne weergeeft, maar ook het geluid uit de tijd van Sint Cuthbert opnieuw tot leven wekt.

Watson vangt in de vier seizoenen het natuurlijke leven op het eiland in een kwartet composities. En niets dan dat. De magie van de opnamen ligt erin besloten dat elke vorm van menselijke activiteit afwezig is. Ongerept en onaangetast waant de luisteraar zich te midden van de dieren, planten en natuurkrachten. Het is dan ook niet moeilijk voorstelbaar dat Sint Cuthbert en zijn medebroeders het eiland Lindisfarne zo gehoord hebben bij hun eerste aankomst. Samen met de stemmige hoesfotografie van Jon Wozencroft, presenteert Chris Watson zodoende een soort auditief archeologisch monument en moment. Door te focussen op wat nog resteert, komt de geschiedenis tot leven; hoorbaar en ontastbaar, voorbijgaand in de tijd, maar toch even helemaal nu in de duur van dit fascinerende album. [Sven Schlijper]

le son du grisli (France):

Quand on se promène au bord de l’eau, comme tout est beau, dixit Jean Gabin, qui avait omis d’y mentionner les chants des oiseaux et les embruns iodés. Qu’à cela ne tienne, un bon demi-siècle plus tard, le magnifique Chris Watson démontre une nouvelle fois qu’il est le maître des field recordings, ici captés sur l’île de Lindisfarne (alias Holy Island), tout au nord de l’Angleterre.

Lieu de vie au VIIe siècle d’un moine anglo-saxon qui donne son titre à cet In St Cuthbert’s Time, l’endroit se prête magnifiquement aux explorations naturalistes de Watson, tant sa biodiversité est rendue avec une précision sonore des plus stupéfiantes. Le résultat est d’autant plus magique qu’on imagine aisément le nombre d’heures passées à capter la sauvagerie marine des lieux, quatre saisons durant svp, pour mieux en retirer une moelle des plus substantielles, échelonnée sur quatre titres (un par saison) d’une quinzaine de minutes chacun. Hip hip hip Watson. [Fabrice V.]

Hawai (Chile):

Bastan unos pocos minutos para abstraerse de la realidad impuesta y sumergirse en el paisaje ambiental que rodea los sonidos de la vida silvestre, unos segundos para adentrarse en un paraje completamente opuesto. Cuando solo transcurren unos instantes, el ruido de la flora y fauna inmaculada inunda las mareas con sus sonidos salvajes, formando una preciosa panorámica de naturalismo prístino. El oleaje cubre las costas con sus frías aguas, y sus habitantes originarios interpretan melodías imposibles de transcribir, asombrosamente impredecibles, pasmosamente hermosas. La obra del inglés Christopher Richard Watson, desde que inicia su trabajo más personal, ha estado siempre ligada al registro de los sonidos que surgen de la naturaleza, capturando la música que nos es imposible poder escuchar, internándose en los espacios más recónditos e inexplorados de la vida aún virgen. Esa exploración cruza todo su cuerpo artístico, en obras como “Outside The Circle Of Fire” (Touch, 1998), “Weather Report” (Touch, 2003) o, las más recientes, “El tren fantasma” (Touch, 2011) y “Cross–Pollination” (Touch, 2011) [170], este último junto a Marcus Davidson.

“Para celebrar la exhibición de los Evangelios de Lindisfarne en la Catedral de Durham, Chris Watson ha investigado en el ambiente sonoro de la Isla Sagrada como debió ser experimentado por San Cuthbert en el año 700 D.C.”. La Isla de Lindisfarne, o The Holy Island, es una isla de mareas a dos millas de las costas de Northumbria, en el norte de Inglaterra, lugar donde en siglo VII un hombre decidió aislarse del mundo y dedicarse a la búsqueda divina, en un entorno maravilloso. “Cuthbert fue un monje anglosajón, un obispo y ermitaño que se convirtió en prior de Lindisfarne en el año 665. En su vida tardía Cuthbert se sintió llamado para ser un ermitaño y trasladarse a la cercana isla del interior de las Farnes para luchar contra las fuerzas espirituales del demonio en la soledad. Cuthbert se convirtió en un socio de las aves y otros animales, y le dio especial protección al pato Eider, el que aún es conocido localmente como pato Cuddy”. En este contexto de soledad y separación del mundo es que se crean estos evangelios, y en ese mismo sitio Watson se ubica para registrar los sonidos que circundaron su estancia y su aislamiento. “A través de la historia humana artistas han sido influenciados por sus alrededores y los sonidos del paisaje que habitan. Cuando Eadfrith, obispo de Lindisfarne, estaba escribiendo e ilustrando los Evangelios de Lindisfarne en esa isla a fines del siglo VII y principios del siglo VIII, el se pudo haber sumergido en los sonidos de la Isla Sagrada mientras creaba este extraordinario trabajo”, señala Chris Watson. “Esta producción intenta reflexionar sobre los aspectos diarios y temporales de una envolvente variedad de sonidos ambientales que acompañaron la vida y trabajo durante este período de excepcional pensamiento y creatividad”. Durante las cuatro estaciones del año, Watson se internó en la geografía de la isla, en los territorios baldíos y la vegetación húmeda. A pesar de que la fisonomía ha sufrido cambios durante los más de mil años que han transcurrido, de todas maneras podemos introducirnos en la historia y, más aún, sentir cómo el paisaje se filtra por los poros de la piel, atravesando las barreras artificiales. Y eso es algo que este artista sabe muy bien hacer. Su técnica consiste en dejar los sonidos que espontáneamente se producen de forma inalterada, conservando la esencia más radical de los mismos. Watson es más un documentalista que exhibe las imágenes tal cual como él las percibe, trasladando la panorámica silvestre de forma inmutable desde su origen hasta la belleza del plástico. La presencia humana se reduce a quien sostiene el micrófono y capta todo lo que le circunda. El resto, ruido realista que emerge de las mareas indecisas y la multiplicidad de organismos que la habitan. La tierra convertida en granos gruesos se funde con los vientos que soplan como un aliento frío, mientras las aguas limpian las riberas que separan el suelo del mar y los pájaros sobrevuelan la playa. La lluvia invernal trae consigo el clima más duro, un temporal de lluvia que humedece las plantas enraizadas a pocos metros del nivel del mar. El terreno recostado permite una visibilidad completa de la isla, una linealidad que contrasta con la variedad de sonidos que surgen en ella. “La marea se retira alrededor de la isla hacia un horizonte distante marcado por una línea de olas rompientes y los profundos tonos del envolvente oleaje sobre las lejanas arenas”. Es invierno en el norte de Inglaterra. “Winter” es el primer movimiento de esta impresionante obra, donde la lluvia convive con los muchos animales que reciben su baño. Patos, cisnes, cuervos y un zorro, entre otros, una fauna que crea una sonoridad abismante, múltiples tonalidades que confluyen en un mismo cauce inestable. “En las aguas altas en la línea de la ribera una reunión de tierra y aves de mar se mezclan en la lenta marea”. Es primavera, la luz entrando por la divisoria del sol. “Lencten”, con el estruendo marino como una constante y sus movimientos acuáticos, además permite oír por primera vez al pato Eider y su extraño canto, una voz muy similar al de una joven mujer. Quizás por eso de la relación estrecha de estas aves con San Cuthbert, quizás con ellos podía establecer un diálogo en la inmensidad de su vacío, en la soledad más allá de las paredes de su monasterio. “Ostreros dan la alarma bajo una ventisca de golondrinas árticas defendiendo sus nidos situados en la playa”. Verano y calor relativo. “Sumor” y la brisa meciendo suavemente el mar, generando tiernas olas que llegan y se retiran de la arena gris, al mismo tiempo que algunos pájaros trazan sus líneas de vuelo, mientras otros se ven “atraídos por una hueste de insectos”. La agitación que fue “Winter”, el alboroto de la estación helada tiene su claro contrapunto en este instante de la rotación, cuando el sol se acerca más próximamente a nuestros rostros. La tranquilidad del océano permite que el sonido silvestre fluya de forma relajada. “En el cielo patrones de estorninos cambian de forma rápidamente sobre sus gallineros situados sobre el silbido de los juncos”. Otoño, última temporada. “Haerfest” y el retorno de las fuertes brisas marinas entre focas y permanente movilidad acuática. A veces parecen voces de fantasmas quienes hablan a través de sus gargantas. Finalmente, poderosas olas cubren el terreno frágil, y la delgada hierba se oculta bajo el horizonte que se confunde con el suelo. Las grandes planicies de tierra líquida detienen su sonido, pero continuarán siendo el escenario para esta asombrosa vida salvaje.

El hermoso canto de las aves, el gemido de los animales, el susurro de las plantas y sus hojas al encontrarse entre sí, la hierba balanceándose conforme se delinean los vientos, el estruendo minúsculo de los insectos. “In St Cuthbert’s Time. The Sounds Of Lindisfarne And The Gospels” es una impecable obra de música espontánea, exquisitamente presentada –libreto de 24 páginas con fotografías de Maggie Watson, con diseño y dirección de arte de Jon Wozencroft–, que traduce el sonido de un momento único. Chris Watson y sus grabaciones en los campos abiertos crea una espectacular vista sobre las islas en la soledad del mundo, a través de su paisajismo geográfico y el ruido natural que brota de la flora y fauna silvestre.

Dusted (USA):

Lindisfarne is a place steeped in mystery and spirituality, the remote home of Irish monks and exploratory hermits. Its very name conjures up images of the wind-swept wildness of the northeastern coast of England; of an island lost in the seas, rich with spiritual energy and dominated by an ancient castle, the vision of which is as inescapable as the swirling gales, crashing seas and, more charmingly, the abundance of bird life that has populated Lindisfarne since, well, St Cuthbert’s time.

And in one album, former Cabaret Voltaire man Chris Watson has managed to spirit us back to the medieval age that made Lindisfarne’s above-stated reputation what it is today. Forget hauntology. More ghosts and fictional memories traverse In St Cuthbert’s Time than any album currently on the market.

The album celebrates an exhibition of the famed and mysterious Lindisfarne Gospels, a series of texts written by the island’s 8th-century bishop, Eadfrith. To make it, Watson decided to spend a certain amount of time each season on the island, using his variety of recording device to capture the very essence of the island’s lonely existence. It has been incorrectly claimed that no human sounds can be heard on In St Cuthbert’s Time. Still even if this is incorrect, the presence of Homo sapiens among the array of field recordings Watson deploys is so discreet as to be unrecognizable.

Instead, the listener is treated to nature at its most vibrant and, at times, hostile. The opening “Winter” is dominated by omnipresent gusts of wind, cascades of icy-sounding water and the constant chatter of birds. One can almost hear the gulls and gannets huddling against the cold, their chorus of croaks and whoops sounding like so many complaints about the bitter conditions.

Things are not much more welcoming on the second track. “Lechten” is full of the sound of water, either falling from the sky or crashing ominously against the coast. Watson has a gift for creating a mind’s eye vision of the landscapes he’s capturing in sound. Closing your eyes during these tracks instantly conjures up the grass, cliffs and beaches of Lindisfarne. I’m not so good at divining the animals, but some of the sounds they produce, be they mammals, fish, birds or insects, are at times charming, hilarious and even downright creepy.

Chris Watson’s aim was to imagine what Lindisfarne would have been like for those early religious folk stranded out in the wilds of the North Sea. Of course, we can’t know for sure that he succeeded, but there’s no denying that In St Cuthbert’s Time is a sonic poem that will resonate with anyone ready to take the time to plunge into his evocative creation. [Joseph Burnett]

Hawai (Peru):

Bastan unos pocos minutos para abstraerse de la realidad impuesta y sumergirse en el paisaje ambiental que rodea los sonidos de la vida silvestre, unos segundos para adentrarse en un paraje completamente opuesto. Cuando solo transcurren unos instantes, el ruido de la flora y fauna inmaculada inunda las mareas con sus sonidos salvajes, formando una preciosa panorámica de naturalismo prístino. El oleaje cubre las costas con sus frías aguas, y sus habitantes originarios interpretan melodías imposibles de transcribir, asombrosamente impredecibles, pasmosamente hermosas. La obra del inglés Christopher Richard Watson, desde que inicia su trabajo más personal, ha estado siempre ligada al registro de los sonidos que surgen de la naturaleza, capturando la música que nos es imposible poder escuchar, internándose en los espacios más recónditos e inexplorados de la vida aún virgen. Esa exploración cruza todo su cuerpo artístico, en obras como “Outside The Circle Of Fire” (Touch, 1998), “Weather Report” (Touch, 2003) o, las más recientes, “El tren fantasma” (Touch, 2011) y “Cross–Pollination” (Touch, 2011) [170], este último junto a Marcus Davidson.

“Para celebrar la exhibición de los Evangelios de Lindisfarne en la Catedral de Durham, Chris Watson ha investigado en el ambiente sonoro de la Isla Sagrada como debió ser experimentado por San Cuthbert en el año 700 D.C.”. La Isla de Lindisfarne, o The Holy Island, es una isla de mareas a dos millas de las costas de Northumbria, en el norte de Inglaterra, lugar donde en siglo VII un hombre decidió aislarse del mundo y dedicarse a la búsqueda divina, en un entorno maravilloso. “Cuthbert fue un monje anglosajón, un obispo y ermitaño que se convirtió en prior de Lindisfarne en el año 665. En su vida tardía Cuthbert se sintió llamado para ser un ermitaño y trasladarse a la cercana isla del interior de las Farnes para luchar contra las fuerzas espirituales del demonio en la soledad. Cuthbert se convirtió en un socio de las aves y otros animales, y le dio especial protección al pato Eider, el que aún es conocido localmente como pato Cuddy”. En este contexto de soledad y separación del mundo es que se crean estos evangelios, y en ese mismo sitio Watson se ubica para registrar los sonidos que circundaron su estancia y su aislamiento. “A través de la historia humana artistas han sido influenciados por sus alrededores y los sonidos del paisaje que habitan. Cuando Eadfrith, obispo de Lindisfarne, estaba escribiendo e ilustrando los Evangelios de Lindisfarne en esa isla a fines del siglo VII y principios del siglo VIII, el se pudo haber sumergido en los sonidos de la Isla Sagrada mientras creaba este extraordinario trabajo”, señala Chris Watson. “Esta producción intenta reflexionar sobre los aspectos diarios y temporales de una envolvente variedad de sonidos ambientales que acompañaron la vida y trabajo durante este período de excepcional pensamiento y creatividad”. Durante las cuatro estaciones del año, Watson se internó en la geografía de la isla, en los territorios baldíos y la vegetación húmeda. A pesar de que la fisonomía ha sufrido cambios durante los más de mil años que han transcurrido, de todas maneras podemos introducirnos en la historia y, más aún, sentir cómo el paisaje se filtra por los poros de la piel, atravesando las barreras artificiales. Y eso es algo que este artista sabe muy bien hacer. Su técnica consiste en dejar los sonidos que espontáneamente se producen de forma inalterada, conservando la esencia más radical de los mismos. Watson es más un documentalista que exhibe las imágenes tal cual como él las percibe, trasladando la panorámica silvestre de forma inmutable desde su origen hasta la belleza del plástico. La presencia humana se reduce a quien sostiene el micrófono y capta todo lo que le circunda. El resto, ruido realista que emerge de las mareas indecisas y la multiplicidad de organismos que la habitan. La tierra convertida en granos gruesos se funde con los vientos que soplan como un aliento frío, mientras las aguas limpian las riberas que separan el suelo del mar y los pájaros sobrevuelan la playa. La lluvia invernal trae consigo el clima más duro, un temporal de lluvia que humedece las plantas enraizadas a pocos metros del nivel del mar. El terreno recostado permite una visibilidad completa de la isla, una linealidad que contrasta con la variedad de sonidos que surgen en ella. “La marea se retira alrededor de la isla hacia un horizonte distante marcado por una línea de olas rompientes y los profundos tonos del envolvente oleaje sobre las lejanas arenas”. Es invierno en el norte de Inglaterra. “Winter” es el primer movimiento de esta impresionante obra, donde la lluvia convive con los muchos animales que reciben su baño. Patos, cisnes, cuervos y un zorro, entre otros, una fauna que crea una sonoridad abismante, múltiples tonalidades que confluyen en un mismo cauce inestable. “En las aguas altas en la línea de la ribera una reunión de tierra y aves de mar se mezclan en la lenta marea”. Es primavera, la luz entrando por la divisoria del sol. “Lencten”, con el estruendo marino como una constante y sus movimientos acuáticos, además permite oír por primera vez al pato Eider y su extraño canto, una voz muy similar al de una joven mujer. Quizás por eso de la relación estrecha de estas aves con San Cuthbert, quizás con ellos podía establecer un diálogo en la inmensidad de su vacío, en la soledad más allá de las paredes de su monasterio. “Ostreros dan la alarma bajo una ventisca de golondrinas árticas defendiendo sus nidos situados en la playa”. Verano y calor relativo. “Sumor” y la brisa meciendo suavemente el mar, generando tiernas olas que llegan y se retiran de la arena gris, al mismo tiempo que algunos pájaros trazan sus líneas de vuelo, mientras otros se ven “atraídos por una hueste de insectos”. La agitación que fue “Winter”, el alboroto de la estación helada tiene su claro contrapunto en este instante de la rotación, cuando el sol se acerca más próximamente a nuestros rostros. La tranquilidad del océano permite que el sonido silvestre fluya de forma relajada. “En el cielo patrones de estorninos cambian de forma rápidamente sobre sus gallineros situados sobre el silbido de los juncos”. Otoño, última temporada. “Haerfest” y el retorno de las fuertes brisas marinas entre focas y permanente movilidad acuática. A veces parecen voces de fantasmas quienes hablan a través de sus gargantas. Finalmente, poderosas olas cubren el terreno frágil, y la delgada hierba se oculta bajo el horizonte que se confunde con el suelo. Las grandes planicies de tierra líquida detienen su sonido, pero continuarán siendo el escenario para esta asombrosa vida salvaje.

El hermoso canto de las aves, el gemido de los animales, el susurro de las plantas y sus hojas al encontrarse entre sí, la hierba balanceándose conforme se delinean los vientos, el estruendo minúsculo de los insectos. “In St Cuthbert’s Time. The Sounds Of Lindisfarne And The Gospels” es una impecable obra de música espontánea, exquisitamente presentada –libreto de 24 páginas con fotografías de Maggie Watson, con diseño y dirección de arte de Jon Wozencroft–, que traduce el sonido de un momento único. Chris Watson y sus grabaciones en los campos abiertos crea una espectacular vista sobre las islas en la soledad del mundo, a través de su paisajismo geográfico y el ruido natural que brota de la flora y fauna silvestre.

Liability (France):

Le field recordings a ceci de bien qu’il permet d’aborder un nombre infini de sujet à partir du moment où l’on maîtrise les méthodes d’enregistrements et que l’on sait associer astucieusement les sons. Pour cet album, qui est une œuvre de commande de l’Institute of Advanced Studies de l’université de Durham, Chris Watson s’est mis en tête de remonter le temps, du moins d’une manière sonore. Le point de départ de cette quête est une exposition sur les Evangiles de Lindisfarne, une île située sur la côte de la Northumbrie, qui est accessible à marée basse grâce à une chaussée submersible et sur laquelle se trouve un monastère ainsi qu’un château. Saint Cuthbert qui dirigeait le monastère instaura ce que d’autres ont vu comme les premières lois concernant la protection des oiseaux. Sur ces informations, Chris Watson a voulu restituer une ambiance sonore telle qu’on pouvait la concevoir au Xème siècle (période pendant laquelle ces Evangiles richement enluminés, comme d’autres l’on été, furent conçus) rythmé par les saisons, l’activité humaine que l’on devine ascétique et spartiate ainsi que la vie animale que sont ces oiseaux pêcheurs qui ont toujours peuplé ces îles. C’est cette environnement sonore qui accompagnait la vie monacale et plus de mille ans plus tard il est peu probable que cela ait beaucoup changé. Dès lors on peut imaginer grâce aux enregistrements de Chris Watson quel pouvait être l’état d’esprit de ceux qui vivaient sur Lindisfarne à l’époque. Une île qui aujourd’hui, pour une bonne partie, est devenue une réserve naturelle et sur laquelle on recense environ 300 espèces d’oiseaux. Chris Watson avait donc une large matière à explorer. Ceci étant, ce disque reste et demeurera comme un album de field recordings dans toute sa splendeur et dans une approche que l’on pourrait qualifier d’absolue. Watson, n’apporte ici que peu voire pas du tout d’effets annexes. Il se contente d’assembler les données brut, restituant une ambiance, un espace mais aussi une présence. Une présence animale, certes, celle que l’on devine plus aisément mais aussi une présence humaine qui est plus diffuse, plus discrète, qui se veut plus comme observatrice et, en un sens, spirituelle. In St Cuthbert’s Time est à prendre comme un document sonore, richement illustré qui ne peut se comprendre que si on se penche sérieusement sur l’objet de sa conception. Le sujet et l’œuvre, ici, sont indissociables. Après, ce n’est plus qu’une question de perception.

The Sound Projector (UK):

Another work which uses the four seasons structure is Chris Watson’s In St Cuthbert’s Time (TOUCH TO:89). The idea of it is simple – field recordings made in Lindisfarne, of the weather conditions and wildlife and the seashore, limited to what St Cuthbert himself, or any other seventh century saint, would actually have heard on Lindisfarne at the time, hence the subtitle “A 7th Century Soundscape of Lindisfarne”. As it happens, I visited the Lindisfarne Gospels exhibition last summer (2013) when it was at Durham, and an installation version of Watson’s work was conincident with the exhibit. I made my way to a small side chapel in the Cathedral and was half expecting an extremely “immersive” event with a large PA and surround-sound effects. Instead, the field recordings were playing back over a pair of modestly-sized white speakers, no bigger than what you may have for your PC. This was the artist’s intent; he expressly wanted to keep playback at a low volume, I think to create a suitably unobtrusive ambience, sounds you had to strain to hear, and to suggest a non-specific spiritual dimension through the act of concentration. The booklet is packed with mini-essays about the history of Lindisfarne, the structure of the Anglo-Saxon calender, the creation of the Lindisfarne gospels, and the life of St Cuthbert. The sound art itself is structured around the four seasons, and the field recordings document the avian wildlife one would tend to hear in that area around Winter, Lencten, Sumor and Haerfest. Birds, water, air – it’s all extremely pleasant to listen to, and the recordings are vivid and clear, but unlike with previous Watson compositions, I’m not hearing that much depth of meaning. Most conspicuously absent for me is the strong – almost mystical – sense of location that is usually one of his signature themes; his best field recordings have been undeniably rooted in the geographic location whence they came, a point firmly emphasised by the citation of grid references. However, in this instance, that would be to ignore all the components of the package which do strongly connect the work to Lindisfarne: sound, texts, images, photographs, and the selection and arrangement of the field recorings themselves. While not quite the time-travel experience one might hope for from the title, this is an accomplished piece of work. From July 2013.

Musique Machine (UK):

This cd from the esteemed Chris Watson is packaged with a wealth of text and images – and so it should be, since the project comes as part of research backed by the Institute of Advanced Study, Durham University. Sometimes, I think this kind of funded work can be problematic; depending on what exactly the funders wish to see for their money… But, in this case, Watson has been allowed to work his magic; though I feel he remains somewhat restricted by the task at hand.

The album comes as a result of study carried out on the small island of Lindisfarne, most famous for the Lindisfarne Gospels – an illuminated manuscript created in the late 7th and early 8th century. Essentially, Watson sets out here to attempt to recreate the sonic/aural landscape that Eadrith – the writer and illustrator of the Gospels – would have inhabited during his work. This is an interesting act of time travel, an imagined recreation of the past; as well as legitimate historical work in its own right.

So, given the information above, what elements do you think will dominate the recordings? “Birds, sea and wind?” Correct. This is where the inherent restrictions of such a project kick in – it runs the risk of being “accurate” at the expense of being sonically “interesting”. The field recordings are layered into constructions, but not (apparently) “processed”; though there are points where Watson has chosen his spot to make use of natural echoes and reverbs – transforming birdsong into near-synth sounds. Thus we are left with “straight” soundscapes made out of unaffected field recordings. Its “worthy”, but it can never escape its self-defined boundaries…