CD – extended digipak – 2 tracks – 39:25

Voice, cello & electronics: Hildur Gudnadottir

Recorded & mixed by Tony Myatt

Mastered by Denis Blackham

Artwork & Photography by Jon Wozencroft

Track listing:

1. Prelude 4:11

2. Leyfdu ljosinu 35:14

Hildur Gudnadottir’s new album ‘Leyfdu ljosinu’ (Icelandic for ‘Allow the light’), was recorded live at the Music Research Centre, University of York, in January 2012 by Tony Myatt, using a SoundField ST450 Ambisonic microphone and two Neumann U87 microphones. (NB – It was not played in a concert environment and there was no audience.)

To be faithful to time and space – elements vital to the movement of sound – this album was recorded entirely live, with no post-tampering of the recordings’ own sense of occasion.

A multichannel version (Touch # TO:90USB) is also available – a 2GB USB stick in hand-made (by the artist) paper cover.You can read more about this here.

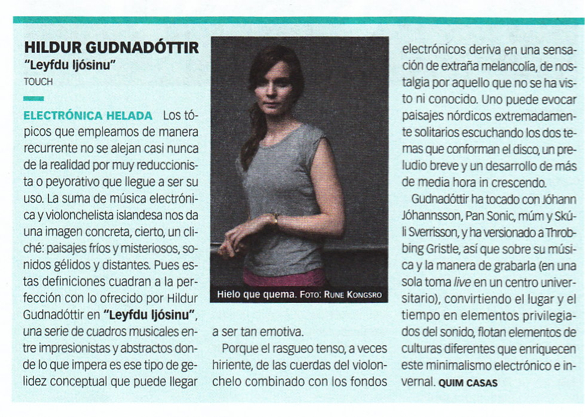

Reviews:

Brainwashed (USA):

On her third solo album (the title being Icelandic for “Allow the Light”), Hildur Guðnadóttir presents a performance that is entirely live (without audience) of just cello, voice and electronics, which begins deceptively simple, but is soon molded into a rich work of intimate beauty as much as it is a complex study of the most rudimentary sounds in a compelling structure.

Consisting only of two pieces, the short “Prelude” is exactly that: a short, sparse opening of dry, unaffected cello playing that may have functioned as much as a warm-up for Hildur as it does for the album as a whole. It leads directly into the 35-minute title track, and the album proper.

Opening with the continued cello and the addition of delicate vocals, the same sparse, intimate vibe continues, insinuating basic expectations for the rest of the album: from the sound and manner of recording, I was expecting an entire album of only strings and voice. Soon the cello drops away entirely, leaving just the vocals to be carefully looped and processed (in real time) into layers, any actual words become secondary to the melody created from the effects.

The returning cello cuts through the fragmented pieces of voice, resulting in a rich combination of natural and electronic sound that builds in density, resulting in a swirling mass of sound that takes a slightly darker turn, hovering ominously over droning low-end cello. The sound shifts in its closing, where the cello becomes less about texture and more about taut, rhythmic swipes that are layered upon themselves, resulting in a jarring, rapid motif that builds and builds into a suspenseful coda, ending what is mostly a reflective, contemplative piece on a tense, almost unsettling note.

As a completely live work, Leyfðu Ljósinu speaks volumes of Hildur Guðnadóttir’s ability as both a composer and performer. The building of sound from a delicate voice and cello to a heavy, swirling mass of sound and closing on a tense, rapid note works extremely well from a structural perspective, and the fact that it was all performed in real time with no overdubs or post-processing makes it all the more exceptional.

soundcolourvibration.com (USA):

Icelandic cellist and vocalist Hildur Gudnadottir has shocked me this year with the awe inspiring live performance album Leyfdu Ljosinu on the UK based imprint Touch. Recorded live with no audience at the Music Research Centre, University of Yorke in January of this year, the flowing essence of minimal presentation is astounding and as powerful as anything I have heard this year. Minimal in approach, Hildur Gudnadottir presents a four minute intro of eerie and slowly burning cello that sets the tone for the type of atmosphere that is to follow on Leyfdu Ljosinu. The following track contains the self titled piece and runs for almost forty minutes as one movement that shifts in various cycles that closes out the album. There is an underlining emotion and feeling that takes over the album, something that defines the albums purpose so well. It’s unbelievable how Hildur Gudnadottir achieves some of the layering that she does with electronics, cello and her vocals and it’s all very angelic and harmonious, never drifting outside of the realm of crystalline beauty. The climax of vocals, cello and electronics at the end is definitely worth the slowly building energy that this album paces at and displays a stunning performance of her cello capabilities with no post production involved.

Much of Leyfdu Ljosinu drifts and floats into different cascading cloths of color, folding inside of itself as each drifting moment cycles around to the other. The atmosphere feels cinematic and speaks for as much tension and restrain as it does muscular power and velocity. Leyfdu Ljosinu is really a remarkable testament to the importance of minimalism in ones music diet. As many albums strive to become large, this is the type of sound that feels large from the smallest of sources and the sound that isn’t being played by instruments becomes just as important as those present. In this world, the type of microphones utilized, a rooms acoustics and many more elements that lay unspoken in the albums final result become factors that give a much greater weight to the music than most contemporary records and is one that engineer Tony Myatt pulled off remarkably.

With vocals that sound like they are hardly surfacing through the depth of a blanketed forest in a lucid dream, intricately vibrant and softly placed loops and an overall musical imagination that paints thousands of pictures, Leyfdu Ljosinu truly becomes a magical and otherworldly vibration. [Erik Otis]

textura.org (USA):

Icelandic cellist Hildur Gudnadottir’s Leyfdu ljosinu (Icelandic for ‘Allow the light’) was recorded live in a single take at the Music Research Centre at the University of York in January 2012. No post-performance manipulations were applied, making the recording as accurate a rendering of the performance as possible. A solo recording in the truest sense, Leyfdu ljosinu finds the classically trained Gudnadottir (aka Lost In Hildurness) extending dramatically upon the sound-world presented in the work by using electronics to multiply her cello and voice. Loops are generated that then sustain themselves as base figures against which subsequent vocal and cello elements resound.

Opening with the cello alone and at its most natural, the brief “Prelude” lays the groundwork for the thirty-five-minute title track. Extended rests separate the bowed tones, almost as if to suggest the music’s awakening, until Gudnadottir’s soft voice appears to signal the start of the major section. An almost ghostly mood is created when her ethereal voice softly intones for minutes on end, the music’s hypnotic character reinforced by the lulling, to-and-fro motion of its rhythms. Fourteen minutes into the second track, the cello starts to challenge the willowy vocals for dominance, the instrument swelling into rather cloud-like formations as it floods the aural space with its dramatic presence. Blocks of heaving strings surge dramatically, and a single cello eventually splits off from the whole, making it seem as if a single voice has risen to the surface of a turbulent, blurry mass, and grows ever more agitated as the end nears.

Gudnadottir makes full use of the title track’s generous length to shape the music’s arc with patience and deliberation. In fact, the growth in density occurs so gradually, it occurs almost imperceptibly, and it’s only when one reaches the end of the recording that the overall shape of the material comes retroactively into clearer focus. Though it’s admittedly more of a cello-based performance than cello-based composition, Leyfdu ljosinu presents a fascinating exercise in control in terms of execution and vision in terms of conceptual approach.

The Liminal (UK):

I’m given to thinking about space more and more at present – in a figurative and a literal sense. And call this hubris, but I can’t be the only one to have noticed this as a broader trend in cultural commentary. Everywhere I look I seem to see a new clamour for space – room – both in the forms under discussion, and something more indefinable, like a new, less frantic place to observe from. It feels almost like a reifying of the metaphoric critical claim for the high ground. It might also be characterised as a plea for stillness, to return to those near-sacred spaces of the past, those (probably illusory) zones which from this rocky vantage point look so full of pure experiential calm and purpose. And my instinct with all this is to say that it’s not just a continuation of the postmodern flattening of things, nor the concomitant ‘flattening’ of sound associated with MP3 culture, and not merely a ‘men of a certain age’ thing (which I’m tempted to call the End of Music syndrome) or a simple waning of affect – this feels new, or at least there’s enough different strands feeding into it for it to sound like a new cry.

That use of the word sacred is contentious (how could it be otherwise) but I’m not sure what other word fits, as tonally at least, this plea for space and the zone itself does have a whiff of the sacred. No other artform excites the easy need for reverence quite like music does (though you could argue it was there in the post-impressionists, particularly Rothko, and some would say too obscurely in Blanchot and the later post-structuralists), and ‘serious’, protective listeners and commentators, are increasingly demanding a shift/return to a kind of monkish devotion when it comes to listening to and commenting on music.

(There’s also, of course, the side issue of the reifying of this sacralising impulse in the continuing fetish for staging concerts in ostensibly sacred places and spaces. Acoustics aside, these concerts don’t perform any subversive function (as discussed by Tony Herrington in an acerbic Wire column), but instead seem to use these spaces in the hope of some referred numinosity or sublimity, a kind of lazy waft at grandiosity that fits with the aforementioned easy need for reverence.)

So what of it? Is there an answer to this cry? Is it merely a generational thing – ageing bodies doomed to chart the clicks and whirrs of metabolic degradation?

* * * * * * * *

I wouldn’t want to characterise the entirety of its output, but there’s always been a trace of the sacred about a lot of the music released by Touch- and a genuine appreciation of space, both in and around the artists they’ve worked with and the methods they’ve used in recording and production, and subsumed in the sound itself. Much of the music makes demands of the listener – contemplation, immersion – and their appreciation of the tactile, fetish-like qualities of product also feeds into this. (By sacred I do mean in the most secular way possible, less in a religious aspect than in a devotional one, something close to Schopenhauer’s awed notion that ‘music floats to us as from a paradise quite familiar yet eternally remote… it reproduces all the emotions of our innermost being, but entirely without reality’. ) And if you were to select a modern figurehead for Touch’s loose ethos, you’d be hard pushed to find a better example than Hildur Guðnadóttir.

Guðnadóttir’s solo work to date is infused with this combination of the devotional and the spacious – you could even argue that in her work the inherent relationship between the two ideas/realms becomes increasingly obvious. The simplicity of what she does is at the heart of things – that unadorned nakedness of her cello, relying on its rough beauty of tone and timbre – but there is an ineffability to this simplicity that explanations only ever really brush up against. With Leyfðu Ljósinu it’s as if she’s reached the central secret of this simplicity, and there’s a real feeling of the inadequacy of language in attempting to identify it.

Take that title – Leyfðu Ljósinu. There’s an immediate sense that the phrase is untranslatable, that you’re only getting a hint of the meaning. It loosely translates as Allow The Light, which when you try and parse it, feels incomplete and kind of hovers between grammatical and lexical possibilities. It’s a command, but like Schopenhauer’s dictum, it sort of drifts in from another realm; and it’s also an impossible command, because one is unable to find a place of control – instead you have to wait, and let the natural order take its course. Which is as good an analogy for the experience of listening to Leyfðu Ljósinu as I can think of: it isn’t something you grasp and contain, rather you surrender yourself to it and (there needs to be a word for this) find a space of aural contemplation.

Leyfðu Ljósinu was recorded at the Music Research Centre, University of York in January of this year (2012). It was recorded live (without with an audience) and there has been no post-production tampering at all – all the sound processing (such as it is) took place during the 40 minutes of the performance. The ‘Prelude’ consists of little more than a two note cello figure, that rises out of the subterranean depths and sinks once more. This figure acts as a kind of undulating bedrock, the echo of which remains in and just out of earshot throughout the entirety of the main section. This main section begins with Hildur voicing a similar two note repeating figure which is then looped and very subtly layered until it becomes like a layer of vapour over the initial bedrock of the ‘Prelude’. Little else happens for the next few minutes until a thread-thin higher vibrating note is introduced – the introduction of which, seems to induce a sudden concentration on one’s own breathing patterns. The passage of air through the upper reaches of the body.

The resurgence of Guðnadóttir’s cello, when it comes, is low and vast, almost leviathanic – a series of deep, humming notes that swarm beneath everything, and buoy up the already rising vocals. The cello gradually fills the field of the recording, somehow gathering space to itself and the thickening of the air around it is almost palpable. The mid-section becomes, then, a time-warping appreciation of the sonic potential of the cello. Somehow, putting time markers against specific phenomena seems pointless as in reality, what occurs is a kind of expansion: it’s almost as if you’re able to walk around inside the theatre (and sonic) space and feel the instrument as a tactile reality. You start to sense the individual wound fibres of the strings, packed together in their confined wire casings, the bristling hairs of the bow, the raised calluses on the player’s fingertips…

The gradual build to a climax is almost (only almost) anti-climactic in its way, as this contemplative spell is broken, but the enacted drama is a kind of necessary release from the madness of synaesthetic detail – a detail that feels dangerous to contemplate for too long, lest you never find a way out. What this section does need (and has in terms of density), is volume – furniture needs to shake, masonry to crumble…

* * * * * * *

In light of my ramblings in the earlier part of this piece, and these ideas of sacredness and ‘easy reverence’, I’ve been thinking hard about my reaction to Leyfðu Ljósinu. I’ve become more and more cautious about the urge to praise, the desire to confer an undeserving status on objects that either don’t warrant it or to which I’ve scarcely had time to acclimatise. Those of us who turn to art to sate our transcendent urges are in danger of running out of superlatives and cheapening the entire exercise. Which is, I guess, another argument for quietude – a quieter place to listen from.

That said, I’ve noticed myself (and have spoken to others who have had a similar experience) stopping in crowded places to let Leyfðu Ljósinu play itself out, resolve itself. Which is, in its way, a form of worship, a giving over to something external and greater than one’s own self. It’s not something I’m necessarily given to doing (except for maybe when paralysed by the force of the natural world) and I guess my point would be that this space we’re all craving, these zones of sublimity that (however illusory) used to exist, that we used to access without thinking, are still extant, still accessible – it’s just that with age, and the ceaseless flows of noise around, the waymarkers are faded and dimmed. Thankfully we still have those who find new ways of sharpening our senses, however fleeting the moments. [Matt Poacher]

The Silent Ballet (USA):

Icelandic cellist Hildur Guðnadóttir has recorded with bands like Múm and Throbbing Gristle, toured with the likes of Animal Collective, and released two albums on Touch, but somehow her name seems to be absent in discussions about leaders in the experimental/classical realm. What can we say? It’s a male-dominated industry. Guðnadóttir’s latest work, Leyfdu Ljosinu (translation: “Allow the Light”) is a forty minute, two track effort that features just Guðnadóttir, her cello, and whatever live manipulations could be squeezed out. Despite Guðnadóttir’s ties to other artists, she tries to keep her solo work just that – hers alone. Leyfdu Ljosinu exemplifies this mindset, as it was recorded live in one setting, with no post-processing and no audience. The absence of a crowd may or may not be of consequence, but the album certainly sounds as if it was created in an empty space and given all the room it needed to expand and conquer the surrounding noises. When played at low volumes, Leyfdu Ljosinu may seem quaint or charming, but when the audience bares the full force of the music, its haunting, forceful nature is fully revealed through ghastly waves of droning cello. Perhaps its the Icelandic stigma forces this conception, but there is a bitterness on Leyfdu Ljosinu that is not too common of works in this realm, and would certainly be an uncharacteristic move on the part of Peter Broderick, Richard Skelton, Greg Haines, Zoë Keating, Julia Kent, or many of the other more prominent modern cellists. On Leyfdu Ljosinu, Guðnadóttir is carving out her own identity, and it is a wonderful sight to see.

Groove (Germany):

Experimedia (USA):

A lovely album of cello/voice/electronics compositions by Hildur Gudnadottir recorded live at the Music Research Centre (University of York) in January of this year. Touch’s press release notes that the original live recordings have not been edited as “to be faithful to time and space.” The effect of this move is the establishment of a sense of intimacy and even immediacy in these glacially moving string compositions. The album begins with a brief string prelude before the centerpiece, “Allow The Light” takes center stage. Thirty-five minutes in length, the piece is really quite beautiful, with angelic, clarion vocals eclipsing beautiful string arrangements for cello. Midway through the piece its initial frailness gives way to a more spectacular and assertive movement, building to a frenzied mass of bowed strings and booming electricity clouds. Impressive and immersive listening, and typically top-notch presentation by Touch. [Alex Cobb]

VITAL (Netherlands):

‘Allow The Light’ is what the title means, and its a live recording ‘with no post tampering of the recordings’, but its not played in a concert environment and without audience. So I am not sure what point has to be proven here, if any of course, but Hildur Gudnadottir is excellent player of the cello, electronics and voice. Following the short opening piece, aptly named ‘Prelude’, the main course is served, the title piece. For both her cello and voice, Gudnadottir uses loop devices to multi-layer her own playing and while at it, add more new layers – live. A method that is hardly new new these days and shocking, but unlike so many guitarists who keep doodling about with a few simple tunes, Gudnadottir crafts together a whole piece of humming voice, in tune and then slowly adds, little by little, her cello playing, slowly amassing, while voices are disappearing, ending in a grand finale. An excellent, somewhat moody and atmospheric piece of music. Why ‘live without audience’, or ‘nopost tampering’ are irrelevant questions once you heard this. There is not much else to say about this piece: simply a lovely direct piece with a great quality. If Gudnadottir plays concerts like this in front of real audiences: bring it on, I’d say. [FdW]

Off The Radar (France):

Cela ne parlera peut être pas à tout le monde, mais sur papier From The Mouth of The Sun est tout sauf un duo de debutants. Mieux, l’association entre Dag Rosenqvist et Aaron Martin a quelque chose de directement engageant. C’est sûrement que les deux hommes ont été responsables de disques boulversants : le premier nous avait tout simplement giflé avec The Black Sun Transmissions sous son pseudonyme Jasper TX, une leçon de drone/ambient grésillante/modern classical noir qui compte encore comme l’un des meilleurs de sa catégorie il y a tout juste un an ; le deuxième nous est connu pour sa magnifique collaboration avec Machinefabriek et sa plantureuse discographie. Et Woven Tide a tout de la promesse tenue. Tantôt limpide, tantôt bourdonnant, cet ensemble oscille entre modern classical lyrique et orchestration claire-obscure. Ses lignes sont explicites, le trait est assurément précis – grâce notamment à des balises rythmiques en trompe-l’œil. On passe de pièces en pièces comme dans un parcours éclairé à la bougie. C’est peut-être cet aspect populaire et pourtant tranchant qui fait de ces huit titres une si belle balade. Une pièce de référence pour les deux bougres, une de plus, qui se résume comme le croisement entre le meilleur d’Hildur Gudnadottir et la série Xerrox d’Alva Noto. [Simon Bomans]

Heathen Harvest (USA):

Recorded live at the University of York, one woman and a cello was all it look to make this album. Iceland’s Hildur Guðnadóttir will most likely ring bells with the Heathen Harvest readership for her work in Throbbing Gristle and Scandinavian experimental/electronic ensemble “múm”, but here she is alone in another of her solo efforts. I’ll be honest, I didn’t even know Hildur was making her own albums but Leyfðu Ljósinu is her eighth such work since 2006. Don’t let the fact that this is a ‘live’ release generate the idea that you’ll be able to hear the whoop and hiss of an audience in the background – far from it – Leyfðu Ljósinu is a live album in a studio sense only, which means the whole thing was done in one take, free from editing and overdubs. There is no background noise, there is no interference. Everything you hear in this work is purely organic, recorded using nothing else but a SoundField ST450 Ambisonic and two Neumann U87 microphones. It is an exquisitely intimate work.

The idea of intimacy should always create a feeling of the up-close and personal, and this concept is extremely relevant here. The choice to use microphones rather than DI’ing jack-to-jack means that the whole recording has a tactile reality to it. Everything seems so immediate in its proximity that you can feel the soft air wake from the brush of the bow on the cello, sense each scratch of a string and hold each vocal exhalation sensually close. Guðnadóttir is an expert in the multifaceted, through clever use of electronic manipulation she is able to overlay her own vocals and cellowork several times through the album during the live setting, giving the album a feel of the singular and multiple. But even these multiple overlays still seem to retain a personal rather than epic air to them. This album is not about the grandiose, it is about the minimalist, and Guðnadóttir is always careful to ensure that this remains the case throughout the record’s 39 minutes.

Technically, Leyfðu Ljósinu is all about texture. It is an extremely tangible album. Musically, it’s a journey from a heavenly ambient realm into somewhere wholly darker. The title literally translates as “Allow The Light”, an extremely curious title for such an eerie piece of work. Starting off with the tantalisingly slow and meditative repetition of some cello chords, the album very gradually descends into somewhere supernatural and unsettling through the use of repeated sung vocal patterns, musical ambience and eventually, energetic, angst-ridden cellowork. What begins as something meditative and warm snakes its way through sonic pathways of despair and doom towards an angered and violent conclusion before dropping everything and leaving us naked in a miasma of our own bewilderment. Such is the intensity of the closing moments that we almost end up feeling sonically ravished and left for dead, as our perpetrator slits us with her last chords, jilts us in an instant and leaves us at the crest of our own climax. As an audience, for all intents and purposes, we have been very much used.

Leyfðu Ljósinu is masterful at its approach to the minimalist. The album seems to go through four distinct ‘waves’, each building on the last and getting gradually more intense until the closing cadences. It’s hard to accurately categorise this work, but though it’s a classical album in ingredients, it retains a feel of the ambient and dark ambient. The layers are so lifelike and well-pieced together that it reminds me of the truly excellent work Shutûn by the collaboration Troum & All Sides, such is its genius at meshing long ambient sections and giving them their own personality.

More than anything though, Leyfðu Ljósinu is a visual work. The sounds here are so intimate and undeniably real that the album takes on a graphic element. It retains an ability to aggrandize certain colours and associations which will be very personal to each listener. It creates such a sentience within the audience’s psyche that it almost runs its own story in filmic effect, transcending the aural layers into which it’s pressed. On the surface, the title of “Allow The Light” may refer to coaxing the brighter layers out from this piece of minimalist classical music, but more than that it’s a plea for us to see the beauty in everything musically dark. Leyfðu Ljósinu stands proudly in its own category as one of the most authentic, emotive and vivid works in ambient music this year. It lacks nothing.

The Wire (UK):

Other Music (USA):

A stark, breathtaking work from the Icelandic composer and performer, recorded entirely live with no overdubs, just Gudnadottir’s voice, cello and electronic manipulations, using an Ambisonic mic and a pair of Neumanns. The ambiance of the room is thick and intense, with a long, achingly pure vocal and string tones floating in the air as if they have actual weight and body, as the composition builds and recedes, and builds and recedes, over 40 minutes.

Norman Records (UK):

I don’t know a lot about this lady but she did a thing on Sonic Pieces not too long ago with Hauschka that Phil thought was amazing so I’m pretty curious to listen. This album was recorded live in York in a non-concert environment and has all sorts of lovely shimmering drones on it. I don’t have the artwork to hand because of a bizarre mix-up involving Brian, who was originally going to write this review, taking it home with him without the disc in it…which sounds like it was his fault but it was actually mostly mine. Looking at a previous release I see she played cello, zither, processors and voice, so I’m assuming that’s what’s going on here. There’s definitely a cello involved and lots of soft processed drones anyway.

At the start it’s quite neoclassical-sounding but later on we get into somnolent soundscaping business with creeping high and mid tones slowly morphing and swelling in quite a sinister way, with a kind of Lawrence English-ish blurriness, but a slow melodic heart that falls somewhere between Stars of the Lid and Deathprod. It’s well relaxing, actually, and the patient droneophiles amongst you are certain to be completely swept up in the full, soft tones and mournful strings.

Fluid Radio (UK):

It doesn’t seem fair to refer to the community of Icelandic composers as a music scene. Cross the ocean, several aesthetic styles and a decade or two, and revisit late 1990s pop punk for that. Blink-182, Third Eye Blind, and The All-American Rejects may each have produced some terrific music on their own — a true scene, in more ways than one — but tell us without Googling it which one recorded “Graduate.” Give up? So do we.

But back to Iceland, it seems impossible that, 15 years from now, anyone here will confuse the work of Jóhann Jóhannsson with that of Wildbirds and Peacedrums, or the compositions of Ben Frost with those of múm. The community might be tightly-knit, and mutually supportive, but the country’s musical breadth is just as remarkable as its depth. It is often remarked that the relatively small population produces astonishing numbers of world-class musicians, but their artistic range is no less impressive.

Yesterday Touch announced the return of Hildur Guðnadóttir. In the paragraph above we listed four diverse artists or ensembles, born or based in Iceland. Cellist, vocalist and composer Guðnadóttir has worked with each of these and a dozen others, a well-established figure in this small, prolific society. Her previous solo album Without Sinking was a collection of ravishing, deep-throated arrangements for cello, zither, and voice, alongside organ, bass, and clarinet. Yet one-sheets, reviews, and concert announcements — including this review — still rely on the gently backhanded introduction, “Best known for her collaborations with…” Perhaps another collection of relatively short instrumental tracks, however gorgeous, was somehow too anonymous. Just like how — after a few years in the working world — we don’t remember the great university professors, or even the excellent ones. Only those who lectured in their bare feet and brought their dogs to class. Leyfdu ljosinu should help out in this respect.

Guðnadóttir’s third album, Icelandic for “allow the light,” is cut into two installments but was clearly composed and intended as a single movement. (Opener “Prelude” trims about four minutes away from the rest, which clocks in at around 35 minutes. Such an oddly-placed digital marker was probably intended only for the requisite free download.) The arrangement — and from here we’ll only speak of Leyfdu ljosinu as a whole, irrespective of tracks — slowly builds from silence and single cello notes, through adagio harmonies and delicious patches of blank canvas. A whispered vocal loop appears: two-word, two-note melodies, first unedited and accompanied with a single, purring cello, but soon gaining momentum with echoes and slight permutations. This way a choir forms, and it is worth noting here that the album “was recorded live at the Music Research Centre, University of York, in January 2012.” In other words, the buoyant voices and the synthesis of the loops into a separate instrument were achieved in one take. Yet the processing is never used as structure, only as finishing.

The cello begins a gradual return somewhere around the midpoint, in sparse, slicing notes and spotlight accuracy. The specific weight of the first act gives way to a blurred urgency in the second, and for at least a few minutes the sum of string vibrations has a downright ambient fullness. Distinct notations come back into focus during the final minutes, with a punching, kinetic arrangement, a well-earned climax, and a few seconds of breath afterward. It is a long piece, and it doesn’t subdivide well. Much better to take it in during one uninterrupted 40-minute listen. It values colour over pattern, tension over relief. Meaning those already familiar with Guðnadóttir may prefer Without Sinking on strictly aesthetic grounds. But for those of us who are new to her work, and for those who were hoping the follow-up would be something more along the lines of a manifesto, Leyfdu ljosinu is unforgettable. [Fred Nolan]

Playground (Spain):

Según la web de Touch, la traducción del islandés de “Leyfdu Ljósinu” sería algo así como “permite que pase la luz”. Pero tal como se desarrolla la composición –una larga pieza de 35 minutos precedida por un preludio de cuatro– parece todo lo contrario, un proceso de progresiva opacidad en el que la luz, que se intuye en los primeros compases y que baña tibiamente la partitura de Hildur Gudnadóttir, se fuera retirando poco a poco, pero de manera inevitable, como cuando se corre una cortina o el crepúsculo va dando paso, directamente, a la noche. La compositora islandesa, a quien habíamos escuchado con anterioridad en grabaciones de Pan Sonic y también en dos emocionantes álbumes en solitario tras haberse deshecho del alias Lost In Hildurness, “Without Sinking” (2009) y “Mount A” (2010), parece ir en busca de un sonido aún más experimental a partir de sus dos instrumentos predilectos, el violonchelo y el ordenador portátil, y mientras antes había entrado con buen pie en territorios neoclásicos, tal como sonaría una tocata de Bach si fuera deconstruida en un laboratorio ambient, ahora se lanza de cabeza en el minimalismo más duro, golpeando en las puertas que delimitan la frontera con la estética drone, buscando el vacío que hay antes del silencio.

Su manera de tocar, que antes era imaginativa y virtuosa, se ha reducido a unas cuantas notas que pasan por el tamiz electrónico para acabar diluidas en una atmósfera acuosa, y al chelo electrificado, reducido a un simple palmetazo que aparece y desaparece, suma también su voz, un susurro que no se distingue entre la respiración de un ángel o la llamada de socorro y clemencia de un condenado al infierno. Y a medida que avanza la composición, esa sensación humana va desapareciendo en beneficio de un lenguaje cada vez más frío, automático y hasta cruel, de ahí que mi percepción del título sea la contraria a la que indica, más una huida de la luz que una aproximación a ella. Durante esos 35 minutos Hildur teje y desteje un tapiz sonoro que cada vez se hace más denso y presente, y la voz, que flota con cierta ingenuidad fantasmal, llega un momento en el que desaparece para que su espacio lo ocupe una nota de chelo vibrante, gruesa y emitida sin variaciones, como un drone que cae como una gota malaya. No es, en ningún caso, una escucha placentera.

Tampoco es, por desgracia, una composición atrevida. Si Hildur ha querido transmitir una idea de luz, su disco se vuelve demasiado oscuro e inhabitable como para llevarnos ahí. Si su idea era encontrar un punto en común entre su impresionismo académico y el drone, evidentemente ahí se sitúa, pero a costa de perder la atención del oyente en muchos momentos, sin avanzar en esa economización máxima del sonido que ya había sido explotada, más y mejor, por compositores como Gavin Bryars –para muestra, búsquese en el mismo sello la última lectura que se ha hecho de “The Sinking Of The Titanic”, con apoyo electrónico–. Aunque esa sea su principal virtud, “Leyfdu Ljósinu” peca de demasiado minimalista, porque no sabe sostener la atención ni la narrativa pasados cinco, diez minutos desde el comienzo, y su final, que se resuelve con un clímax de intensidad, se vuelve demasiado predecible, aunque la transición es lo suficientemente prolongada –un cuarto de hora, aproximadamente, con mayor presencia del chelo y retirada de la electrónica– como para incluir muchos segundos en los que se siente una profunda zozobra emocional.

En definitiva, Hildur está en una fase experimental, ha grabado esta composición en tiempo real, sin overdubs, y eso al menos es sintomático de que no ha perdido su técnica prodigiosa. Pero de este disco se podía esperar más, una mayor concentración de ideas, porque en su afán de minimalismo confía en sostener 40 minutos de interés con sólo dos o tres matices y, por desgracia, todavía no tiene la pericia para conseguirlo. Pero hay que confiar en que su “Jesus Blood Never Failed Me Yet” pueda llegar pronto, al fin y al cabo es a lo que aspira. [Robert Gras]

Ondarock (Italy):

Nel curriculum di Hildur Guðnadóttir sono raccolte alcune tra le esperienze più importanti della musica moderna. Cantante e violoncellista dal training classico, attiva da una decade nell’ambito della sperimentazione musicale, ha contribuito all’avventura di numerosissimi nomi fondamentali tra cui Pan Sonic, Throbbing Gristle e, sopratutto, Múm, dei quali è divenuta membro fisso a partire da “Go Go Smear The Poison Ivy” (2007). Nel frattempo ha proseguito il suo cammino di ricerca nel laboratorio sonoro Touch, con un’attività solista all’insegna della fusione tra l’estetica glitch e i lancinanti e oscuri parti sonori del suo violoncello, dando vita a tre album di pura sperimentazione elettro-acustica e a una collaborazione con il guru dell’ambient-glitch BJNilsen.

Il nuovo capitolo della sua saga raccoglie un’improvvisazione di quaranta minuti tenutasi al Centro di Ricerca Musicale dell’Università di New York. L’islandese “Leyfou Ljosinu” si può tradurre in “Lascia spazio alla luce”, e rende perfettamente l’idea dell’accezione data alla straordinaria performance. Quaranta minuti di droni elettro-acustici, smagliature sonore, cori sovrapposti e trattamenti elettronici alle ancestrali ouverture di violoncello. Il rinnovamento concettuale della definizione di musica d’ambiente portato avanti dall’islandese nella sua ricerca trova il suo punto focale in questi trentacinque minuti di innovativa avanguardia elettro-acustica, in cui l’applicazione della musica all’evocazione e allo spazio circostante si evolve: il flusso sonoro che parte dall’intrinseco rapporto con i gelidi landscape islandesi, dagli stessi si solleva posizionandosi in un ambito metafisico, slegandosi completamente dallo spazio con il quale formava un sinolo.

È il trionfo della forma, della perfezione tecnica. Dove prima v’erano suoni in simbiosi con gli oggetti e le immagini circostanti, questi ora si rapportano in legami solo con loro stessi.

I quaranta minuti di “Leyfðu Ljósinu”, pertanto, scorrono tra vuoti e pieni, silenzi e compassate grida. Si parte, quindi, dal mondo terreno, nella sua visione più astratta, dal minimale incedere di lunghe note di violoncello nei primi cinque minuti dell’overture di “Prelude”, che suonano come una preparazione prima della partenza, una sorta di riscaldamento. Il vero inizio arriva con il minimale incedere di note di pianoforte che perdono la loro carica col trascorrere dei minuti, in corrispondenza dell’arrivo di tessiture elettroniche già proiettate verso una cornice parallela. La voce fa la sua comparsa poco dopo: le sillabe sono sfruttate come droni, ripetuti ciclicamente, sul modello caro al movimento minimalista, e procedono così verso una scalata. L’astrazione è lenta, progressiva, non vi sono sbalzi né testacoda, solo un continuo fluire che cattura elementi man mano che s’innalza. Ancora sample, tappeti, qualche disfunzione, poi il violoncello e nuovi archi vocali: ma la sfumatura è così lenta, così progressiva da impedire quasi del tutto di rendersi conto del continuo movimento. Verso la metà della composizione, si tocca il picco espressivo con l’urlo silenzioso di tutte le sue componenti in simultanea, e con il violoncello che va a sostituire la voce nel ruolo di protagonista.

La salita non è terminata, la catarsi è ancora lontana. Il violoncello comincia a distendersi, a lasciar fuoriuscire le sue coordinate, e, languido, inizia il ritratto di atmosfere prive di emozione. L’ascesa prosegue e non c’è elemento che induca alla frenata, né suggerisca quando e dove il tutto possa terminare. Si inizia ad acquisire velocità, non sparisce minimamente la sfumatura evolutiva, e la catarsi estatica arriva nei tre minuti che precedono il termine: dal silenzio iniziale ora pare di stare udendo un’intera orchestra sinfonica, il violoncello viene trattato attraverso l’ausilio del laptop, le sue linee sonore moltiplicate allo sfinimento, è un grido fortissimo ma silenzioso, che conquista ma senza spingere, che emoziona ma senza sfiorare il cuore. Poi, d’improvviso, il tutto scompare, illude di aver raggiunto il punto più alto, ma un minuto dopo la corsa riprende, supera la velocità della luce, ma solo per poco. Dopodiché, il silenzio. Resta l’eco lontana a impedire di definire come, dove e se il percorso sia terminato, il cerchio chiusosi. La risposta non può essere data, non è né affermativa né negativa. E’ semplicemente astratta, indefinita, come ciò che l’ha preceduta.

La straordinaria esperienza sonora a cui pochi fortunati hanno avuto l’onore di assistere lascia alle sue spalle un’eredità fortissima, un’unione geniale di tecnologia e concetto, un risultato estasiante per la ricerca di una delle artiste più innovative del panorama attuale, in grado, dopo aver alloggiato alla corte di numerosi importantissimi nomi, di coronare la sua carriera dando vita a una delle opere più importanti della scena d’avanguardia del nuovo millennio. [Matthew Meda]

Chain D.L.K (Vito Camarretta):

Recorded live at the Music Research Centre of York University by Tony Myatt last January, by means of a Sounfield ST450 Ambisonic microphone and two Neumann U87 microphones, with no audience and above all with no post-production, this 40-minute lasting release by talented Icelandic cellist and singer Hildur Gudnadottir stands like an act of devotion to her musical vision, merged during her career into many artistic felloships – she’s a permanent member of Mum since “Go Go Smear The Poison Ivy” and she could boast about important collaborations with Throbbing Gristle and Pan Sonic -. After 5 minutes of tuning in Prelude, starting with a do (C) on cello and various harmonic flexing, and the beginning of her entrancing vocal mantra, which becomes ethereal and hypnotical thanks to vocal overlapping, “Leyfdu ljosinu” (Icelandic for “Allow The Light”) transforms into an authentic sonic theophany whereas there’s a cyclic alternation of empty spaces close to silence and sonic saturations and the performer looks like a medium experiencing and translating of the divine, a purpose she manages to reach by overloading ths onic space with an increasing metaphysical tension, which immediately grabs the listener, who could experience a weightless-like feeling of suspense. Little by little, cello and additional arches sounds like expanding like clouds, and such an expansion looks like unstoppable and endless even when bow-strings sound like stretched to the limit and amplify tension and overwhelming catharsis, according to an ascending movement which could remind the sonorities of records like the collaboration between Sigur Ros and Hilmar Orn Hilmarsson for the soundtrack of “Angels of the universe” or Zoe Keating’s soundtracks. Highly recommended!

Radio France (France):

“Beaucoup plus classique que celle d’Anthea Caddy, l’écriture de la violoncelliste et compositrice islandaise Hildur Gu?nadóttir n’en n’est pas moins intéressante pour autant. Cette artiste, dont nous avons déjà à plusieurs reprises écouté d’autres extraits d’enregistrements, participe à la tournée 2012 de David Sylvian quand la fragile santé de celui-ci le lui permet. En parallèle, elle continue de créer son univers musical très personnel pour le cinéma, la danse ou la scène. Son travail est influencé tant par sa formation classique, son goût pour les musiques actuelles et les traditions folkloriques de ses origines. Hildur Gudnadóttir utilise en parallèle de son instrument, le timbre de sa très jolie voix, quelques manipulations électroniques et à parfois également recours à l’image. Le label Touch vient de publier un nouveau recueil de cette artiste exceptionnelle, un album enregistré très récemment à York, en concert en janvier 2012. Très bien enregistré d’ailleurs puisque c’est Tony Myatt lui-même, le directeur du centre de recherche Musicale de York, qui s’est chargé de cette très belle prise de son en choisissant d’utiliser un micro SoundField ST 450 et un couple de de Neumann U87. Intitulé Leyfdu Ljosinu, cette nouvelle production se compose de deux plages : l’une de quatre minutes autour d’une composition pour violoncelle seul, l’autre de trente cinq minutes dans lequel elle utilise ses talents de chanteuse et de manipulatrice sonore. L’ensemble est aussi séducteur qu’ensorcelant.” (Eric Serva pour France Musique – Mai 2012).

Tyzden (SK):

SvD (Sweden):

Debug (Germany):

Sonic Seducer (Germany):

Musikansich (Germany):

Klusak (Czechia):

Polibek na cello

S nástroji jako je klavír, violoncello a harfa se v posledních letech něco stalo. Autoři narození v šedesátých až osmdesátých letech přišli s vlnou jakýchsi neoklasicistních koncertů: ale už se do nich fatálně vtiskla zkušenost s elektronikou, autorským popem a dalšími přístupy. Někdy je to spíš takové libé cinkání, i „nezávislé“ publikum má své Jiří Malásky: viz úspěšný důsseldorfský klavírista Hauschka nebo jeho britský kolega Max Richter. Když Richter (s asistencí samotné Tildy Swinton) pracuje s textem Franze Kafky, je to tak strašně moc prodchnuté krásou, že byste místo Kafky tipovali spíš na Irenu Obermannovou. Ale pak se najednou vynoří někdo tak nekompromisní jako cellistka Hildur Gudnadóttir, důvod tohoto sloupku.

Ke svému průlomovému albu Without Sinking (2009, psal jsem o něm) připojila islandská hráčka příběh. Jde v něm o to, že byvší členka kapely Múm se stala žádanou spolupracovnicí. Její otevřený přístup k cellu využívali finští elektronici Pan Sonic, zároveň Hildur vytvářela s kontroverzními legendami Throbbing Gristle soundtrack k filmu Dereka Jarmana. Bydlela v Berlíně i Reykjavíku a tak dlouho létala z koncertu na koncert, až se začala zabývat tvarem oblačných kup, které vídala za okýnkem letadla. “Chtěla jsem ve skladbách vytvořit nebe a pocit plynoucích oblaků. Dát tónu otevřený prostor a nechat ho dýchat, jako osamělý oblak na jasném nebi.”

Na čerstvém albu Leyfdu ljosinu (vydal londýnský Touch), což znamená islandsky Vpusťte světlo, neupřesňuje, „co to má být“: čtyřicetiminutovou plochu si každý může vykládat, jak chce. Nahrála ji bez publika, ale je to neupravený záznam živého hraní: dokonce snímaný nikoli kontaktně, ale třemi mikrofony rozestavěnými okolo, protože Hildur si přála „zůstat věrná prostoru a času, prvkům životně důležitým pro šíření zvuku“. „Neužívám hráčské techniky druhých lidí,“ říká o hledání svého způsobu zacházení s cellem, které vedlo přes klasickou akademii, islandskou uměleckou komunitu Kitchen Motors i pařížský institut INA – GRM, jednu z prvních akustických laboratoří elektronické hudby.

Výsledek nese stopy každé z těch štací. Na začátku Hildur do hry zpívá dva tóny, kyvadlo se pořád vrací, jako by bylo potřeba odbýt rituál. Dech hlasu a tvar tónu náhle tvoří zrcadlový sál: Tělo se připodobňuje cellu, cello se připodobňuje tělu, cello i tělo společně odkazují k něčemu třetímu, realita se ve víru zvukového proudu obrací zpět a otiskuje hráčce polibek na cello…

Pak se věci pohnou: playbackem vrstvené cello zazní jako celá sekce. To netrvá dlouho: různé témbry na sebe začnou narážet a cellový rezervoár se rozbouří. V proudu zvuku slyšíme gong, harmonium, hoboj, baskytaru, vzdálené hřmění, indickou tampuru, kytarové plochy Hilduřiných krajanů Sigur Rós nebo lokomotivu. Po všech metamorfózách se cello v rytmickém finále zase nechá poznat, následuje už jen dlouhý výdech.

„Děti Arva Pärta“: odkazem na estonského skladatele nazval kdosi scénu, kam patří i Hildur Gudnadóttir. Krása v jejich pojetí není symetrický ornament: připodobňuje se spíš generativní harmonii, jakou mají kořeny stromu, skvrny na zvířecí srsti, ale i pavučina ulic dobře stavěného města. V západní Evropě neslyší lidé o nic líp než u nás: ale vytvořily se tam už komunity posluchačů i profesionálů, kteří podobnou hudbu umisťují na větší festivaly, propagují coby výraz dneška, veřejně sdílejí. Lidé v hledišti nezřídka reagují, jako by přišlo něco, co jim chybělo.

RNE (Spain):

La chelista islandesa Hildur Gudnadóttir, es conocida por su obra en solitario y por sus colaboraciones con artistas electrónicos experimentales como Ben Frost, Nico Muhly, Pan Sonic o Throbbing Gristle.

Tenemos su último disco “Leyfdu Ijosinu”, que significa algo así como “Acoge la luz” en islandés.

El disco captura una actuación de Gudnadóttir en la Universidad de York ofrecida a principios de este año. El concierto fue grabado con la ayuda de tres micrófonos: un SoundField ST450 Ambisonic y dos Neumann U87. El contenido de esta grabación se ha dejado tal cual, sin manipular para respetar el tiempo y el espacio de este concierto, elementos vitales para el movimiento del sonido.

Black Audio (net):

The Touch label has always been synonymous with the word ‘quality’ and once again this is no exception. ‘Leyfdu ljosinu’, or ‘Allow the Light’ is a live recording with no audience, recorded at the University of York in January 2012.

I love the idea behind the concept; no post tampering of the recordings using three microphones for natural delay; the end result is nothing short of stunning.

I was utterly transfixed at this release from the moment I hit play; there is something utterly ghostly about the production as a whole, with soaring beautiful female vocals, cello and light electronics and is ‘other worldly’ if I had to try pigeon hole it.

The quality of the instrumentation played and composition is utterly spectacular and quite simply nothing like I have really sat down to listen to before; tension builds towards the latter half of the title track with a real sense of urgency and drive. You get he feeling a real story is being told here with a polar opposite approach to the lighter sections balancing out the more hectic momentum that builds throughout, blending the two with utter perfection.

I absolutely adored this release and really wanted more; this is the only downside being you get 40 minutes spread over two tracks and what would have set this off would be track markers along the way so you can skip to the parts you want to play most.

I suppose there can’t be any real complaint if that’s all that is wrong with an album; I really wish there were more releases out there with so little to grumble at; Utterly glorious.

9.5/10

Titel (Germany):

Rockerilla (Italy):

NMusik (Germany):

ambientblog.net:

Hildur Gudnadóttir ‘s latest release on the Touch label features two tracks: the 4 minute introduction (“Prelude”) and the 35 minute title track: “Leyfdu Ljósinu ” .

The track division seems is somewhat artificial, since the “Prelude” closing chord seamlessly introduces the start of the main title track.

This recording is in fact a “live” recording (with no audience present. which means no distractive audience sounds).

It’s “just” Hildur performing over her multi-track recordings – no “post tampering” was applied afterwards.

Hildur’s main instrument still remains the cello. The Prelude is a cello solo performance, but as soon as the main track starts there’s a sudden change of mood when the cello retreats and it’s Hildur’s voice that is layered to slow angelic whispers – seemingly taking inspiration from Brian Eno’s classic “Music for Airports” as well as more recent Grouper recordings. The main difference is the way the tension slowly rises.

“Leyfdu Ljósinu ” takes the time it needs to develop. Gradually, a different atmosphere creeps in, and after about 15-20 minutes the cello reclaims its place center-stage and the tension starts to rise to an inescapable climax in the end, sounding nothing like the start.

A solo-performance with a full scale symphonic effect!

“Leyfdu Ljósinu ” is Icelandic for ‘Allow the light’ – but I’m not really sure if the light is coming in or if it is forced to retreat.

Apart from the physical CD-release, Touch also offers this album on a 2GB USB stick featuring a surround version by choice (4-channel, 5.1 with bass management or 5.1 with full LFE).

The performance recording was made using ambisonic microphones, so this multichannel version will probably enhance the recording environment surroundings (of the Music Research Centre of the University of York).

The USB stick version comes in a Hildur handmade paper cover. Oooh.. talk about tempting!

Black (Germany):

GMD (France):

Rencontrer la musique d’Hildur Gudnadóttir est l’une des plus belles choses qui nous soient arrivées ces dernières années. Peut-être parce que jouer un modern classical si intense a quelque chose d’anachronique dans une époque où tout va vite, où tout se consume aussi vite qu’on le consomme. De toute manière, on était quasiment obligé d’aller vers cette musique. D’abord et avant tout car nous sommes des fanatiques du label Touch Music, référence indiscutable de l’expérimentation sonore et de la beauté tonale. Connue internationalement pour être la partenaire idéale pour qui souhaite un accompagnement de qualité supérieure au violoncelle – on pense notamment à Pan Sonic, Animal Collective ou Ben Frost – c’est véritablement sur disque qu’on est tombé amoureux de la belle au nom de bûcheron.

On la découvre avec le magnifique Without Sinking, déjà sur Touch, où Hildur nous a littéralement pénétré (…) avec une vision unique du concerto pour violoncelles : lent, spatial et infiniment triste, le modern classical d’Hildur Gudnadottir envoûte avec sobriété. De là, une flopée de prix en tous genres, une réputation qui gonfle et une humilité qui semble être la constante dans une carrière qui n’a pourtant pas peiné à démarrer. S’en suivra un deuxième album, Mount A – originairement le premier de sa carrière – qui continuera de magnifier ce sens de l’attaque sur les cordes et cette obsession pour le tournoiement sonore. Enfin, ce qui nous intéresse ici est quelque peu différent. Quelque peu seulement.

Troisième disque pour la jeune Nordique, qui décide cette fois de capter son art au vol, dans les conditions d’une pièce live ininterrompue. Pas d’overdub, pas de retouche post-op’, tout est dans la performance : ça passe ou ça casse. S’il n’y a que deux titres sur ce Leyfdu Ljosinu – littéralement «qui autorise la lumière » – on ne saura qu’être élogieux à propos des trente-cinq minutes que couvrent le magnifique titre éponyme (le premier titre, « Prelude », étant une jolie introduction de quatre minutes dans un genre bien connu de l’Islandaise).

Alors qu’elle tenait une patte musicale prête pour durer des siècles, Hildur Gudnadottir va se mettre en danger en troquant une matérialité contre une autre. De son emprise sur des cordes franches, l’Islandaise va se déplacer cette fois sur le terrain du drone. Leyfdu Ljosinu va encore plus en s’étendant, tisse un réseau fort entre électronique tonale et véritable chaleur acoustique. Dans les quinze premières minutes, le drone monte, presque sans attaque sur cordes, avec un chant effilé et intégré dans la masse sonore. Et puis il y a ces vingt dernières minutes qui nous laissent tout simplement sur les fesses : les cordes virevoltent, la gravité est à tous les coins de notes. Le magma sonore augmente sans cesse, avec un ratio puissance/lenteur dont elle seule a le secret, jusqu’à atteindre l’insoutenable émotionnel dans les dernières minutes. Le disque s’arrête, et il nous faudra plusieurs minutes avant d’ouvrir la bouche. On se contemple alors très loin de nous-même, bien conscient que ce disque a quelque chose d’exceptionnel. Peut-être son meilleur disque.

Go Mag (Spain):

Kindamuzik (Netherlands):

IJsland profileert zich de laatste jaren meer en meer als voedingsbodem voor ingetogen snaarexperimenten, vaak verder bouwend op een klassieke muzikale aanpak. Hildur Guðnadóttir past in deze recente traditie maar toonde eerder al met Without Sinking en Mount A aan dat ze toch nog enkele andere accenten legt waardoor haar solowerk plots ook andere dimensies aanneemt. Naast haar eigen werk was Guðnadóttir als celliste al actief bij onder meer Múm, Jóhann Jóhannsson, Angel, BJ Nilsen en Stilluppsteypa.

Ingetogenheid en minimalisme tekenden haar eerdere solowerk. Op Leyfdu Ljosinu slaat Guðnadóttir nieuwe wegen in, terwijl ze trouw blijft aan de sereniteit die haar muzikale aanpak zo beklijvend maakt. Haar nieuwste release bevat twee delen, een vier minuten durende ‘Prelude’ en een afsluitend hoofdnummer van zo’n vijfendertig minuten. Dit laatste draagt de titel van het geheel.

Leyfdu Ljosinu is een oefening in traagheid en geleidelijkheid en dat is meteen de sterkte ervan. Guðnadóttir werkt met stem, cello en elektronica en dit laatste zorgt ervoor dat ze gaandeweg meer muzikale lagen kan opbouwen die het geheel steeds complexer maken en zo stilaan naar een climax toewerkt.

‘Leyfdu Ljosinu’ per sequentie overlopen zou aan de essentie voorbijgaan. Door de graduele opbouw van stemmen en cello weeft Guðnadóttir een intrigerend tapijt van meeslepende klanken die naar het einde toe op een eigen, abstracte manier verwijzen naar de intensiteit van bijvoorbeeld Godspeed You! Black Emperor. Maar Guðnadóttir laat zich moeilijk vergelijken en lijkt in de eerste plaats op zichzelf. Leyfdu Ljosinu is dan ook een volgende stap in Guðnadóttirs boeiende muzikale loopbaan, en een die nieuwe deuren opent. [Hans van der Linden]

Radio Student (Slovenia):

V Tolpi Bumov tokrat poslušamo ploščo islandske čelistke Hildur Guðnadóttir z naslovom „Allow The Light“. Na njej se Hildur predstavlja v za njene standarde precej izčiščeni različici – zgolj s čelom in glasom. Striktno gledano pa bi morali k temu dodati še laptop, ki ga uporablja za živo zankanje in nasnemavanje zvokov čela. Hildur smo na valovih Radia Študent že slišali, in sicer kot gostjo v elektronsko-noiserskem projektu Angel na izdaji „26000“. Tokrat pa je elektronika predvsem ključno orodje večkratnega potvarjanja suhih, akustičnih zvokov.

Hildur Guðnadóttir izhaja iz tiste islandske scene, ki so jo včasih prepoznavno krojili izvajalci, kot so Björk in Sigur Ros, nekoliko kasneje pa tudi skupine, kot so Múm – s katerimi je med drugimi tudi sodelovala. Zmagovito mešanico avantgardne pop senzibilnosti, odmevov ljudskih glasb, eksperimentalne elektronike ter kinematskih in minimalistično-ambientalnih orkestracij tako nosi v sebi tudi Hildur. Na plošči „Allow The Light“ še posebej izstopa značilno intimen pristop k vokaliziranju, ki se izogiba pevskim nastavkom in jih zamenja za šepetajočo bližino. Kot je že marsikdo opazil, bi lahko govorili tudi o nekakšni svojevrstni in eklektični estetiki uspavank. Tako se po krajšem interludiju začne tudi osrednja skladba plošče. Nežno ponavljanje dvotonske vokalne fraze se prepleta s čelom, ki oscilira med nizkimi pedalnimi toni ter drobnimi fraziranji. Vse skupaj se kumulativno sestavlja v ogromen polifonični drone, ki pa ne poteka premočrtno. Gosto nasnemavanje linij tvori gnetljivo gmoto, ki je harmonsko precej pestra in se kljub jasnemu izhodišču izmika striktnemu minimalizmu. S tem ustvarja občutek, kot bi ta drone v svojem bistvu bil nekakšna razpotegnjena pesem.

Bolj kot skladba napreduje, bolj postanejo očitni tudi koralni odmevi znotraj nje. Le-ti pa napotujejo na utrjen sklop povezav, ki vsebuje tako zgodnjo sakralno glasbo kot tudi njene pretvorbe v delih severnoevropskih minimalistov z Arvo Pärtom na čelu. Vpliv teh estetik pa je moč jasno slišati tudi v njenem igranju čela, ki je nezgrešljivo tonalno in molovsko. Ta svojevrsten klasicizem postane proti koncu že rahlo zadušljiv, saj se stranpoti in skrivnostni odzveni, ki so posledica gostega plastenja, umaknejo popolnemu sprejetju prepoznavnih glasbenih kodov. To je seveda lahko povsem stvar okusa – a ostaja vtis, da je preprost tonalni material v sredici plošče razvit in pregneten na precej zanimiv in odprt način, ki poslušalca povleče noter brez očitne prisile točno določenega estetsko-emotivnega učinka.

Za konec naj omenimo še Hildurino mojstrsko obvladovanje tehnike, ki sicer zaradi nereflektirane in nedomiselne vseprisotne uporabe postaja vedno bolj vprašljiva – govorimo seveda o uporabi loopov. Na tem področju Hildur Guðnadóttir spomni na ameriškega violista, elektrofonika in skladatelja, ki se skriva za imenom Core Of The Coalman. Kajpak s precej manj radikalnim pristopom k repeticiji, loopanju in akumulaciji. Morda si za zaključek lahko privoščimo uporabo staromodnega glasbeno-kritiškega stilskega orodja: recimo torej, da plošča „Allow The Light“ zveni, kot bi se Core Of The Coalman srečal s Sigur Rós nekje na islandskem podeželju.

Clash (USA):

Bad Alchemy (Germany):

Enola (Belgium):

Hildur Guðnadóttirs derde soloplaat (tweede onder eigen naam) Leyfðu Ljósinu is een erg opslorpende ambientrit, bestaande uit een korte prelude en een 35 minuten lange, vloeiende titeltrack, volledig live opgenomen aan de hand van twee microfoons, zonder dat er enige postproductie mee gemoeid werd. Gezien de uitzonderlijke narratieve kwaliteit van de muziek: een kortverhaal met als leidraad deze plaat.

“Laat het licht toe” (Leyfðu Ljósinu) had haar moeder haar meermaals gezegd, “je kan niet eeuwig in die donkerte blijven zitten.” In feite was het zelfs geen kwestie van willen of kunnen, ze kon het simpelweg niet aan om te leven in het constante licht van de poolzomer terwijl ze zichzelf volledig ingepalmd voelde door duistere gedachten. Dus zat ze dagenlang binnen, met de zware gordijnen gesloten en zichzelf diep weggestopt in de bedlakens die ze al maanden niet meer ververst had. Niet meer sinds.

Sindsdien was ze maar zelden buiten gekomen, slechts voor het levensnoodzakelijke, en dan steeds maar korte tijd waarbij ze zoveel mogelijk andere mensen probeerde te mijden. Verder deed ze niets, met uitzondering van het bespelen van haar cello. Door de cello, volgens haar het enige muziekinstrument dat je met je hele lichaam bespeelt, de diepe resonanties ervan zich verspreidend doorheen haar onder- en bovenlijf terwijl ze traag de snaren van het instrument bestreek, behield ze als het ware nog enige voeling met de tastbare wereld rond zich. Het melancholische geluid van haar cello, gekoppeld aan de gevoelsmatige deining die de resonanties teweeg brachten, bood haar een houvast waardoor ze haar duistere gedachten even kon opzij zetten.

Vandaag speelde ze diep verzonken in de muziek, met veel aandacht voor de stilte en met alle ruimte voor de natuurlijke echo, een korte “Prelude” waarin een subtiele melodielijn, opgebouwd uit gestaag verschuivende dubbelgrepen, alle aandacht naar zich toe trok. Eenmaal beëindigd merkte ze dat de resonantie van haar laatste noten langer bleef hangen dan normaal, terwijl rondom haar een vage, hoge vrouwenstem traag en in een gelijkmatig ritme de lettergrepen van “Leyfðu Ljósinu” zong, daarbij steeds naderbij komend, hoewel ze in het schemerduister van de kamer niemand zag en ook geen aanwezigheid voelde. Al snel werd de ene stem vervoegd door een identieke stem die in tegentellen dezelfde syllaben voortbracht. En dan nog een stem, en nog een, en nog een, alsof een engelenkoor haar gestaag omsingelde en een boodschap wou duidelijk maken.

De repetitieve patronen van het koor vormden een vloeiend geluidstapijt dat de subtiele laatste resonanties van de cello overstemde en de kamer volledig opvulde. De klanken overspoelden haar en ze voelde zich als in trance opgetild worden uit haar stoel en zacht naar onder getrokken worden, zonder dat ze echter een aanraking of een letterlijk getrek voelde, waardoor ze zich niet verzette en evenmin angst voelde. Minutenlang bleef het koor haar trage polyfonie voortbrengen, haast ongemerkt verschuivend van akkoord naar akkoord terwijl zij steeds verder naar beneden getrokken werd, diep in het niets, tot ze boven een kabbelend wateroppervlak zweefde. Aan de hand van vage lichtspelingen zag ze dat er een stroming bestond die het wateroppervlak beroerde op gelijke tred met de echoënde stemmen.

Aanvankelijk was die stroming nog rustig, maar wanneer diepe celloklanken de repetitieve koorpatronen verstoorden, eerst nog zacht maar later met krachtige présence, merkte ze dat dit ook een weerslag had op de stroming die alsmaar onrustiger werd. Golven vormden zich, aanzwellend tot een wilde storm, terwijl zij onbeweeglijk te midden van het water- en geluidgeweld hing. Opeengestapelde dissonanten, door de mangel van een hele rits effecten gehaald, vormden het tot voor kort zo serene koor om tot een grillige textuur van klanken, waarbij minutenlang in slow motion gelaveerd werd tussen rustiger stukken en delen waarin verschillende lagen een alomvattend dreunende, haast onhoudbare spanning veroorzaakten, die de golven tot schuimende hoogten deed opruien.

Na daar lange tijd midden in het geweld gehangen te hebben, voelde ze zich weer opstijgen terwijl eerst hoge, en vervolgens korte, gejaagde noten zich in het klanklandschap mengden. Dat werd alsmaar intenser, en toen ze uiteindelijk opnieuw achter haar cello zat, merkte ze dat ze zelf die noten aan het spelen was, haar rechterarm verkrampt de strijkstok omklemmend terwijl haar linkerhand met kracht de snaren ingeduwd hield. Ze voelde hoe ze zelf naar een climax bouwde zonder er controle over te hebben, hoe ze er verschillende minuten op bleef door rammen zonder te weten wanneer het zou eindigen, tot het dat ineens zomaar deed. Enkel een verweesde stilte bleef achter.

In de nagalm en de uiteindelijke stilte voelde ze een rust over zich neerdalen die ze al maanden niet meer had gevoeld. Pas veel later legde ze haar cello opzij en opende ze de gordijnen die een fikse lading stof afwierpen. Door de stofwalm heen zag ze de zon laag aan de horizon in het westen, het was al diep in de nacht. “Leyfðu Ljósinu” herhaalde ze tot zichzelf. [Gowaart Van Den Bossche]

RifRaf (Belgium):

RifRaf (France):

Blow Up (Italy):

The Postrock (Germany):

Was die Isländerin dem Licht erlaubt, ist auf dem 40minütigen Album eindrucksvoll zu hören. Das Album besteht aus einem kurzen “Prelude” und dem 35minütigen Titeltrack. Aufgenommen wurde das Ganze diesen Januar im Music Research Center der Universität von York. Drei Mikrofone haben live festgehalten, was Hildur mit ihrer Stimme, ihrem Cello und eine kleinen Auswahl an Effektgeräten gemacht hat.

Das Ergebnis ist eine mystische Klangreise, die mit schwerfälligen Cellotönen eröffnet wird. Langsam streicht der Cellobogen über die Saiten und entlockt diesem großen Instrument noch größere Klänge, die zugleich weich und schwer klingen. Basssound in seiner filigransten Erscheinung. Der Titeltrack fängt erstaunlich Cellolos an. Hildur setzt nämlich nur ihre Stimme ein. Mal mit echten isländischen Wörtern, mal nur mit dadaistischen Klängen, die allmählich durch die Effekte gejagt werden und übereinandergelegt oder geloopt werden. Es baut sich ein Klangkörper aus Hildurs Stimme auf und man kommt sich vor wie in der Odysee, in der man ja vor den Klängen der betörenden Sirenen gewarnt wurde. Egal, die Anziehungskraft ist so stark, da kann man sich nicht fernhalten. Es vergehen etliche Minuten und langsam schleicht sich der Cellosound ein. Lange schleichende Tönen verwandeln sich in schnellerere fast schon aggressive Klänge. Hildur spielt und spielt und spielt und es klingt immer unaufhaltsamer, bis dann überraschend Schluss ist. Das sind verdammt kurze 35 Minuten…

Evernote (Italy):

La cellista dei Mùm, Hildur Guðnadóttir dà, con la lunga improvvisazione per cello, voce e elettronica di “Leyfðu Ljósinu” (35 minuti), una prova d’arte sensazionistica che deborda nell’esoterismo meno rasserenante, come un dialogo rallentato, e pessimista, tra io e cosmo.

La sillabazione fonetica con cui si apre evoca l’immagine di una flebile Meredith Monk circondata da risonanze indefinite. La voce si fa suono sempre più ascetico e sempre meno verbale, in una forma di minimalismo sfumato che permane allo stato larvale, il corrispettivo di un canto monastico a cappella senza ossigeno.

Al decimo minuto la polifonia si fa spaziale, stretta parente della seconda parte degli “Airports” di Brian Eno, mentre il cello, fino ad ora in sordina, alza il volume. Questa sorta di confluenza tra spazi matematici e tempi irrazionali suona – a tratti – quasi snervante.

I droni degli archi finalmente dominano le voci in dissonanza e affrescano paesaggi ancor più angosciosi; i suoni si moltiplicano, le voci risuonano con tuoni lontani (l’unico vero ritmo in tutto il brano), fino a svaporare del tutto, soverchiate da un inno terribile. La melodia piena di tensione è finalmente detonata da una fuga vivaldiana dal tempo vorticoso.

Libera fantasia registrata live (mirabile precedente: Lisbon” di Keith Fullerton Whitman) con cui Guðnadóttir, classe ’82, splende su quanto fatto in precedenza – “Mount A”, a nome Lost In Hildurness, poi riedito dalla Touch nel 2010 e “Without Sinking”, 2009 -, e si lascia guidare dallo spirito indagatore dell’anima mundi. Neoclassico con facezie d’avanguardia, e un respiro ampio e persino distaccato, un contenitore organico che è sia polittico a fasi in alternanza sia percorso omogeneo. Registrato al Music Research Centre di York con un armamentario notevole (a cura di Tony Matt, ricercatore musicologo) che comprende anche un microfono “ambisonico”. Il “Prelude” è un’elegante toccata per violoncello riprocessato. Titolo tradotto: “Allow the Light”.

Rockarolla (UK):

Gonzo Circus (Belgium):

Hawai (Chile):

Y se hizo la luz. Muchas formas hay de sorprender, pero una de ellas ha llegado a mí de manera inesperada. Un día cualquiera, una semana cualquiera, sin que me lo esperara apareció ante mí una carpeta que una vez entré en ella no pude salir. Las maravillas de lo imprevisto. Hildur Ingveldardóttir Guðnadóttir es una músico islandesa nacida en 1982, chelista y compositora, mayormente reconocida por ayudar a otros artistas como múm, Pan Sonic, Angel (Ilpo Väisänen + Dirk Dresslehaus), BJ Nilsen, y varios más. Hace tan solo seis años se estrena en solitario con “Mount A” (12 Tónar, 2006), bajo el nombre de Lost In Hildurness . De ahí en más ha seguido colaborando, y eventualmente entregando obras encerrada en su soledad, siempre con un punto de vista luminoso, pero de esa luz apreciable solo en el norte del mundo.

El nuevo trabajo de la islandesa fue grabado en vivo en el Centro de Investigación Musical de la Universidad de York, en enero de 2012 usando un micrófono SoundField ST450 Ambisonic y dos micrófonos Neumann U87. Sin embargo, en el ambiente no hubo publico alguno, no es este un registro de una presentación como si fuese un concierto. Nada de gente más que ella, sus instrumentos y aquello con que dejar una huella de ello. “Para ser fieles a tiempo y el espacio –los elementos vitales para el movimiento del sonido– este disco fue grabado íntegramente en vivo, sin ninguna manipulación posterior a la del sentido propio de la ocasión de la grabación”. Un preludio y una pieza central que no suman más de cuarenta minutos en los que Hildur despliega su arsenal reducido en materiales que sin embargo producen una alegría enorme. No se si sea la mejor manera de describirlo, pero ese efecto ha producido en mí. Reposado a ratos, inquietante en otros, en cada instante percibo un gozo al escuchar cada una de sus notas. Chello, electrónica y voz son los componentes por medio de los cuales construye una música exquisita. Atenta un instante, furiosa en otro. “Prelude” da un comienzo sugestivo, segundos en los que abre el camino que desarrollará ampliamente más adelante.

Tranquilidad evocadora de una pureza infinita, que apenas llega a su fin, el segundo once del minuto cuatro da paso a “Leyfðu Ljósinu”, y la manera que lo hace es sencillamente devastadora. En un ritmo muy reposado, en un volumen muy bajo, comienza a advertirse la voz de Hildur, multiplicada por efectos, repetida hasta la eternidad. Parece que para provocar no es necesario hacerlo en voz alta, y eso es lo que ha hecho: en esos instantes iniciales cantando una especie de oración que se niega a partir. Tocando el cielo desde el silencio y lo que se acerca a el. Los monumentos más gloriosos y que más he disfrutado en estos meses. Pasado ese masaje a los oídos, casi en la mitad del trayecto, empieza a atacar con el chelo, a generar el contrapunto a tan balsámico sonido. Poco a poco, muy lentamente una atmósfera oscura se apodera de la sala –me da la impresión que esto fue grabado a oscuras–, como cuando la sombra se apodera de la sol, emergiendo una luz oscura, pero luz al fin. Ya no esta su voz, pero la magia sigue presente. Parecería que su ausencia podría echarse de menos, pero la gloria no se ha ido. Avanzando a escondidas, sus trazos dibujados con finura alrededor de las cuerdas van hilando unas redes finas y muy bien delineadas que forman una sola masa, repitiendo patrones hasta el cansancio inagotable, perturbadoramente atractivos. Esto parecen drones dibujados con cuerdas delgadas. Ya por el final, el ambiente se torna gris oscuro, cada vez más fascinante, cada vez más agitado, terminando por desmembrar la tranquilidad, siempre desde su óptica del orden. Es el minuto número treinta y cinco, y he terminado absorto, felizmente agotado.

Ejecutado con una perfección sorprendente, en la soledad, y combinando el dosis justas los elementos vocales con los instrumentales, “Leyfðu Ljósinu” es un trabajo asombroso, una sorpresa inesperada que llego como del cielo. Si bien se un trabajo relativamente corto, en distancia como en medios, es un disco lleno de matices, con desarrollos largos y prolongados, aumentos progresivos de un encanto extenuante que en cada instante sirven de reflejo de una luz tenue pero incandescente. Por cierto “Leyfðu Ljósinu” es una frase en su islandés, su lengua de nacimiento, y su traducción es ‘permite que la luz’. Y la luz ha entrado.

Les Chroniques (France):

8/10

Le charme sauvage de l’islandaise n’a d’égal que son éternelle humilité. Celle dont le prénom est aussi difficile à écrire qu’à prononcer, est installée depuis quelques temps à Berlin, visiblement définitive capitale pour tout musicien qui se respecte. Même si elle est très loin d’officier dans des sphères mainstream, elle a donné un sévère coup de projecteur sur l’instrument qui lui est cher : le violoncelle. Véritable symbole du label Touch (avec Fennesz et quelques autres), son magnifique Without Sinking et sa miraculeuse collaboration avec Hauschka sur Sonic Pieces, font office d’indispensables pour bien des mélomanes avertis. Son Mount A, signé sous son pseudo Lost in Hildurness, est tout aussi recommandable (peut-être encore plus) même si il est moins souvent cité. Tout ce qu’elle touche se transforme en or. Même si tout le mérite lui en revient probablement, Hauschka fait aujourd’hui le bonheur du légendaire et inaccessible Deutsche Grammophon, référence classique si il en est. Quand on dit qu’elle a également collaboré avec des gens comme Ben Frost, Throbbing Gristle ou Pan Sonic, ça a tout de suite un impact un peu plus évocateur vis à vis de la virtuosité de la demoiselle. Leyfou Ljosinu (Allow The Light en anglais) est sorti il y a quelques semaines chez Touch, entraînant des réactions aussi vives que contrastées.

Enregistré dans les conditions du live au Centre de Recherche Musicale de l’Université de New-York, Leyfou Ljosinu est un album très particulier, mais qui se révélera comme tout sauf anecdotique avec le recul, dans la discographie de Hildur Guonadottir. Outre le fait que le GRM français (Groupe de Recherche Musicale) ai joué un rôle très important dans le projet, c’est avant tout les méthodes d’enregistrement qui ajoute tant de singularité à cet album. Pour d’autres, c’est ce qui déconcerte si j’en crois mes rares lectures sur la virtuelle toile. Quand on parle de méthode d’enregistrement, il faut surtout citer le matériel en question. Un couple de micros électro-statiques (Neumann U87) et un Soundfield ST450. Que des microphones qui coûtent la peau des couilles, et qui sont très difficiles à maîtriser pour ceux qui n’ont pas de réelles connaissances et de maîtrise de l’ingénierie sonore (à ce niveau là on peut même parler de science). Je vous épargnerais l’importance du placement et de la disposition des différents éléments pour profiter au maximum de cette luxueuse installation. Tout le monde sait que les lecteurs de Chroniques Electroniques n’ont strictement aucun intérêt pour le domaine technique.

Ceux qui ont eu la bonne idée de plonger les oreilles dans des titres tels que Light ou Reflection, savent que l’islandaise n’en est pas à son coup d’essai expérimental, et que s’approcher du drone ne lui a jamais fait peur. la démarche n’a pourtant jamais été aussi poussée. Après un Prelude dans la plus pure tradition Hildurienne (à pleurer donc), la fresque est là, ambivalente et ondulée, prête à transmettre son lot de mystères et d’émotions.

L’islandaise connait si bien son instrument qu’elle peut le laisser divaguer vers des trajectoires imprévues. Ce buste de bois qu’elle place entre ses jambes comme un torse masculin, semble même être un prolongement d’elle-même. On comprend vite lorsqu’elle caresse ce pelage de cordes, qu’elle a les armes pour le faire parler, gémir et hurler. Il est l’instrument de son génie, avec toute la noblesse que cela comporte.

La voix s’égraine, des paroles incompréhensibles, voilées, murmurées, mais qui semblent tant dire. Les notes sont amples, installent progressivement le canevas. Déjà, le travail autour de la spatialisation est remarquable. Ce grain, si spécifique aux objets Neumann, et ces mediums qui semblent si lointains, ajoutent à l’atmosphère une tonalité profonde, insondable et solennelle, digne d’un faux conclave en chapelle ardente. Les silences occupent peu mais bien l’espace. La voix se répercute contre des parois poreuses et millénaires. Puis, les notes se resserrent, le thème se gorge d’inquiétude transie. Ce qui se révélera comme une insoutenable attente propice à l’assise de la charge expérimentale (jusqu’à la 23ème minute) , prendra des allures de longueurs pour ceux qui entendent plus qu’ils n’écoutent. L’instrument de toute les attentions déploie sa plainte au milieu des voraces échos. Puis, et c’est là que toute la technique de l’islandaise est impressionnante, la caresse se fait plus violente et plus débridée. On pourrait croire qu’elle saisit ce tronc comme un stradivarius léger comme une feuille d’érable, pour lui arracher ses secrets les plus inavouables. Elle est seule mais l’impression que la scène compte dix concertistes est bluffante. Sans jamais céder à la cacophonie et à la surcharge, les six dernières minutes seront dantesques. Jusqu’à ce désarmant silence, qui rendra ce pavé musical si obsédant. Tout n’est plus qu’absence, avec toute la paix et la frustration conjuguées.

Ceux qui assistérent aux installations de Pimmon, Monolake et Hildur sous l’égide du GRM et de Présences Electronique avaient, pour certains d’entre eux, émis une certaine réserve voire de la déception. Il y a deux écoles dans ces cas là, ceux qui ne jurent que par l’immédiateté des albums en eux même, et ceux qui envisagent la musique (l’expérimentation surtout) dans sa configuration scénique. Il en est de même avec cet album. Déconcertant peut-être, mais tout sauf décevant. L’exigence est la panacée de ceux qui vivent la gueule dans le son. Un album à part donc, mais qui comptera.