CD – 7 tracks – 44:50

Design and photography by Jon Wozencroft

Mastered by Denis Blackham

Track list:

1. Unveiled

2. Chime Again

3. Fanfares

4. Shining

5. Fanfares Forward

6. Residue

7. Fanfares Over

” … the Day

I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity”

(from ‘The Chariot’ by Emily Dickinson)

Sand was recorded live in Holland and England in 2006/7 and edited in Liverpool January, 2008 using Fidelity record-players, Casio SK keyboards, Behringer mixer and sony mini-disc recorders.

Following Philip Jeck’s acclaimed collaboration with Gavin Bryars and Alter Ego on a new version of ‘The Sinking of the Titanic’ (Touch Tone 34), ‘Sand’ is a set of seven new compositions that highlight Jeck’s mastery of vinyl manipulation, personal and collective memories.

During the past year Jeck has refined and consolidated his unique sound, playing superb sets at last summer’s Faster than Sound festival and at York Minster for Spire. He has recently released ‘Amoroso’ [Touch # TS01, 7″ vinyl only with Fennesz] where he responds to Charles Matthews’s homage to Arvo Pärt.

‘Sand’ is at once elegiac, celebrational, mournful and uplifting. Those who have followed Jeck’s development since his first release, “Loopholes” (Touch TO:26) will observe his return to the industrial textures that coloured that collection, though here they are fused with his symphonic grace and continued development as a composer and live performer .

Philip Jeck studied visual art at Dartington College of Arts. He started working with record players and electronics in the early ’80’s and has made soundtracks and toured with many dance and theatre companies as we as well as his solo concert work. His best kown work “Vinyl Requiem” (with Lol Sargent): a performance for 180 ’50’s/’60’s record players won Time Out Performance Award for 1993. He has also over the last few years returned to visual art making installations using from 6 to 80 record players including “Off The Record” for Sonic Boom at The Hayward Gallery, London [2000].

Philip Jeck works with old records and record players salvaged from junk shops turning them to his own purposes. He really does play them as musical instruments, creating an intensely personal language that evolves with each added part of a record. Philip Jeck makes geniunely moving and transfixing music, where we hear the art not the gimmick.

This is Philip Jeck’s 4th solo album for Touch after ‘Loopholes’ [Touch # TO:27, 1995], Surf [TO:36, 1998], Stoke [TO:56, 2002] and ‘7’ [TO:57, 2004]. A companion vinyl release to Sand, ‘Suite: Live in Liverpool’ [Tone 28/FACT11] is being released on US label Autofact later this Summer.

He recently performed on “The Sinking of the Titanic” with Gavin Bryars in Rome, about which Boomkat (UK) said: “The most noticeable addition is Jeck, whose expertise and unique style seems to fit like the final piece of the puzzle as his crackles and motifs melt into the architecture of the recording as if they had always been there. This additional layer of nostalgia brought forth by these found sounds adds a significant sense of history, forcing the mind back into hazy film footage and decomposed photos, a perfect match for the subject matter.”

Reviews:

Pitchfork Media (USA) – reviewed in 2008:

Music built from found sounds is fascinating because it violates a traditional tenet of creativity – namely, that the artifact must be a pure expression of the artist’s will and talent. But it can seem purely academic if the results aren’t engaging. The best process-based art moves us intellectually if we’re aware of the concept, but still moves us emotionally if we aren’t, and that’s what Philip Jeck achieves with Sand. He manipulates, layers, and loops the dead spaces of vinyl – run-out grooves and scratches – and breathes them full of life. That’s awesome, but you don’t need to know it in order to feel the surging power of the “Fanfares” trilogy (which emanates from scraps of Aaron Copland’s wartime anthem “Fanfare for the Common Man”), or to become entangled in the fine-woven web of “Shining”. You could write a dissertation on Jeck’s rehabilitation of lost and damaged bits of cultural information, or you could just get lost in his strange world – as flat and sprawling and complexly shifting as its title implies. [Brian Howe]

Pitchfork Media (USA):

One way to learn about a culture is to retrieve and study what it throws away. The multimedia artist and turntablist Philip Jeck, then, is an excavator. He finds worn vinyl records, tinkers with their surfaces, then plays them on any number of old, sturdy turntables, allowing their layers and loops to build and fall while he folds in bits of keyboard or other effects. Jeck hears things in those old records that others don’t hear– a short, banal passage might be fed through a pedal just so to create a startling new sound, or a saccharine bit of Disneyfied strings might bubble up from a dark cloud of overpowering surface noise. He takes old, discarded junk and sends it back to us like a reflection.

Sand is Jeck’s eighth solo album and, like many of its predecessors, it’s constructed in large part from edits of live performances. He dedicates it to his late mother, and there’s a famous quote inside from Emily Dickinson about death, so it’s about mortality on some level. I also hear Sand as a political record, because of the combination of the album’s title (a possible allusion to the Middle East) and the prominent use of the patriotically charged “fanfare” motif in three tracks. “Fanfares”, “Fanfares Forward”, and “Fanfares Over” are the glue that holds the record together. An element in each is Aaron Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man”, which Copland composed in 1942 as part of series that commissioned new works to uplift a nation at war. “Fanfares” takes a short segment of the original, a whoosh of string and horns all warbly and tumbling over itself, adds bits of delay and noise, and gradually folds the various elements into a constantly shifting drone of overlapping loops.

It’s a powerful track because it triggers so many feelings simultaneously. On one level, the sterling pomp of the “fanfare” is the institution you want desperately to believe in. It’s Cub Scouts learning how to fold the flag, the winner’s circle at the Olympics, a moon landing– music designed to make the heart swell. But Jeck, through the use of surface noise, processing, and editing, dips the sentiment into the acid bath of reality. Sometimes, the passages he samples are assembled to sound like “Taps”. Indeed, you can feel something ending when you listen to “Fanfares”, a way of life crumbling, some sort of dream slipping away. It’s easy to be swept along by the mournful horns, but the constant sense that something is wrong pervades. “Fanfares Forward” shoves the whole burning city of the earlier track underwater, slowing things down and drowning it in an aquatic space with the high-end rolled off. And the closing “Fanfares Over” begins with a broken, dubbed-out calliope, returns to the main theme, and then explodes the whole thing in a perpetual flange filter that feels like strafing jet fighters. These are terrifically complex and layered pieces that are among Jeck’s best.

Unlike parts of Stoke and 7, there’s never a moment here where you are unsure that you are listening to turntables. Beyond the “fanfare” pieces, Jeck finds passages of twinkling, almost sentimental beauty lifted from records of orchestral works (“Chime Again”) and infuses them with poignancy through layering and repetition. He also takes bits of indeterminate sound and stretches them into thin, eerie drones that almost sound like a field recording (“Shining”). You could say that these other tracks find Jeck in his classic mode. On a purely sonic level, however, Sand isn’t his most appealing album. It’s packed with mid-range information and sometimes comes over as blaring, which might suit the material but can be a little tiring to listen to. Still, in terms of its composition and the power of the music, Jeck continues to function at a high level, and he seems to have stepped up his game in terms of emotional complexity. Throughout Sand you can hear opposing forces– grandeur and loss, beauty and ugliness, clarity and ambiguity– bumping against each other, and the tension makes for some seriously rich listening. [Mark Richardson]

The Silent Ballet (net):

Score: 8.5/10

Last year, Philip Jeck contributed his talents to Gavin Bryars’s re-imagining of The Sinking of the Titanic. To many, Jeck’s turntablist underpinnings became the highlight of the new work, which had previously relied on strings and samples. Jeck was the perfect collaborator, having already established himself as a purveyor of the forgotten on such seminal recordings as Surf and Stoke. His previous work had included forays into speed manipulation, notably the adaptations of archival 78s. While these productions were often sublime, they were unintentionally hindered by the vocals, in that the enjoyment of each piece was reliant on an appreciation of each singer’s mutated timbre.

Recent movies have provided some rather ludicrous visions of post-apocalyptic music. In “I Am Legend,” the protagonist plays old Marley tracks. In “Doomsday,” cannibals gather for a lip-synched alternative rock festival, featuring – you guessed it – the Fine Young Cannibals. Many moviegoers wish they could forget the rave scene* in “Matrix: Reloaded.”Sand, however, is exactly what one might expect music to sound like after an apocalyptic event: scuttled beats, snatches of melody, hand-cranked turntables, detritus and debris. In the end, as Alan Weisman writes so eloquently in The World Without Us, sand gets inside everything, working and worrying the cracks until concrete breaks and gears wind down. To quote Czeslaw Milosz, “There will be no other end of the world.”

Jeck is a sonic scavenger along the lines of Mad Max in “The Road Warrior.” One can imagine him digging through dusty crates in a gas mask, searching for the perfect warped sample, a shattered snapshot of lives gone by. On this recording, his cherished finding is “Fanfare for the Common Man,” which he masticates and blunts until all that is recognizable is the central organ riff. This recording becomes the anchor for the entire project, which without a familiar source, might seem more foreign than resonant. On a few occasions, Jeck makes the piece wobble in Kid Koala fashion, but more often he rolls out his sonic source like dough. The pops and creaks of album opener “Unveiled” sputter like crackling stars. The stretched surfaces of “Chime Again” contain flecks of organ layered atop pillowed, extended tones, like echoes in a deserted cathedral. This ghostly effect leaks from the combination of old material and older turntables; but since both source and medium have decayed, the sounds that Jeck makes could not have been made when the records and turntables were pristine.

Ecclesiastes once lamented, “There is nothing new in the whole wide world.” These days, very little music contains the element of surprise. Ironically, Sand seems an entirely new life form, despite having been stitched together from pre-existing atoms. While one might argue that every new brand of music is a combination of old elements, Jeck here does more than simply combine particles – he breaks them down into their base components and reassembles them in previously unimagined ways. The result is unexpectedly poignant.

While Sand may take the form of a fanfare, it possesses the nature of a requiem. At first, the final track seems to go on a bit too long; the glissandos at the end are a bit much. Yet its abrupt end is cause for sorrow. While I would have preferred a quiet fade, it seems oddly appropriate that this world would end neither with a bang nor a whimper, but with an unplugging. [Richard Allen]

Boomkat (UK):

When we last heard from experimental turntablist Philip Jeck he was performing alongside Alter Ego as part of their fresh take on Gavin Bryars’ The Sinking Of The Titanic, casting a sepia-tinged crackle over the recording. Sand is a return to Jeck’s solo work, further exploring the quite unexpected emotional resonance stirred up by old records and their dismantled sonic properties. As ever, Jeck uses old vinyl and decayed audio as a portal into memories, and like the machinations of remembrance, his audio is hazy, obscured and coloured by distortions. ‘Unveiled’ is an apt re-introduction to Jeck’s universe, constructed from waves of pure texture and mist, phasing out of control at first only to permit some recognisable streams of piano to permeate the deep, cavernous crackle. Following directly on, ‘Chime Again’ manipulates recordings of bells, sounding like some psychedelic campanologist’s nightmare. Suddenly the tone shifts for ‘Fanfares’, a piece assembled from recognisable elements of Emerson Lake & Palmer’s recording ‘Fanfare For The Common Man’ [actually its not the version played by ELP – ed.] looped and detuned into a clamorous haze. This is a theme that persists over the course of much of this album’s remainder, with ‘Fanfares Forward’ further making a mockery of this most grandiose of musical forms: the overwhelming, brassy qualities of the previous ‘Fanfares’ have been pared down to a more sedate, distorted loop format, before the lengthy album closer ‘Fanfares Over’ devours an escalating mass of anthemic sounds, coloured by the same spiralling phase effects that commenced the record via ‘Unveiled’. “Sand” is one of Jeck’s most beautiful and approachable releases to date: his source material is so thoroughly dissolved that the music enters the domain of outright ambience more comprehensively than on records like Surf or Stoke – albums that explicitly made use of old gospel and bluegrass 78s. Instead, Sand is more about the processes themselves than the content, forging music from raw texture and effects-driven manipulation. The result is, predictably enough for a Philip Jeck record, quite breathtaking. Highly Recommended.

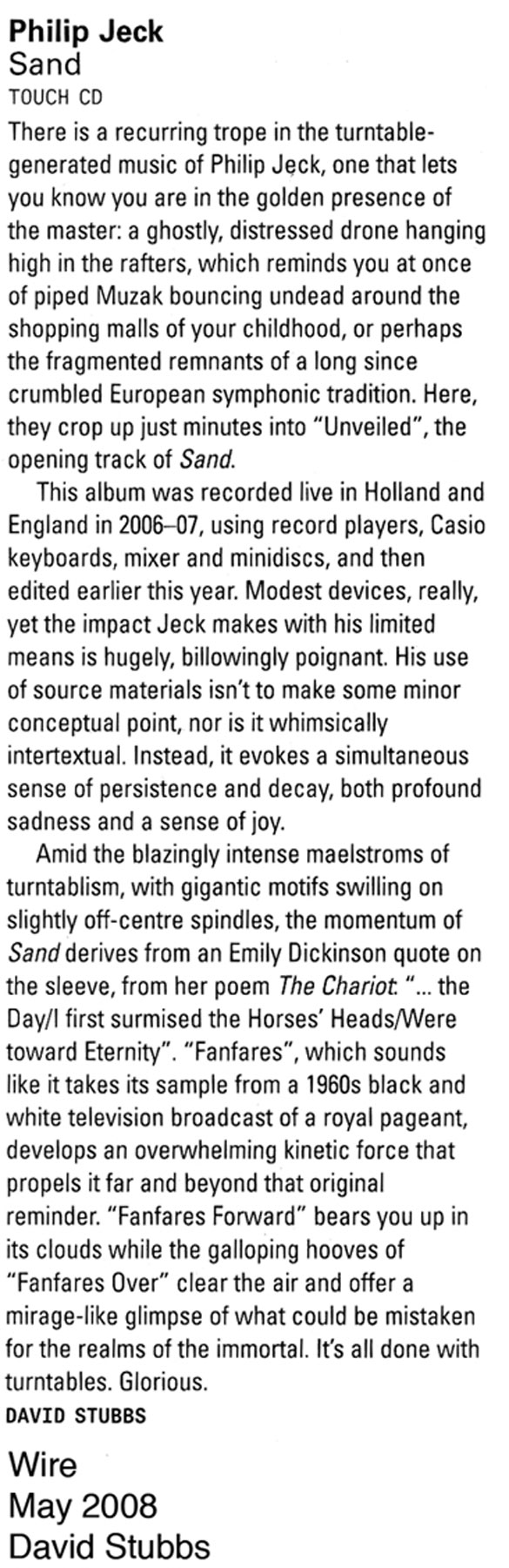

The Wire (UK):

White_Line (UK):

Wringing alternative harmonies, and hidden gestures from over-used vinyl is Jeck’s speciality, and with a clutch of notable releases on Touch so far, his reputation as the enfant terrible of turntablism is without doubt, and still remains unchallenged for this listener.

Recorded in Liverpool, and Holland, SAND sees Jeck drawing from an impressive collection of obscure vinyl, twisted and permutated via his idiosyncratic inventory of Fidelity record players, filtered and distilled through effects, mixers and mini disc recorders. Jeck’s surreal hall of mirrors technique effortlessly generates a hybridised, lo-fi skrim, where one can occasionally pick out the source material, and witness it being subjected to all manner of distortions and deformations, generating an active fabric that is at once alive and constantly mutating.

Here, Jeck appears to have plundered his archive for old recordings of Emerson, Lake and Palmer, as their “Fanfare for the Common Man” emerges as a common theme, particularly on track 3, aptly entitled “Fanfares”. Sometimes, as on Fanfares Forward, the source material is xeroxed away into pure drones and texture, all detail has been erased, whereas Residue flips between perspectives, dropping in oddly paced sequences, creating a disorientating swirl of tones and overlays. Overall, fairly standard fare for Jeck adherents, and a worthy entry point to his work for the neophyte. Recommended. [Barry Nicholls]

musiquemachine (UK):

I’ll have to admit in the past Philip Jeck’s take on ambience and soundart has always underwhelmed me, it just felt too vague, too out of focus and wish-washy. But Sand has really impressed me, there seems a lot more focus, depth and listenability here; the tracks invite you in and make you want to stay and revisit them often.

I guess his sound is best described as a mix of slow monition dj-ing meets ambience and drone expanse; he uses old record players and vinyl to take elements of melody, texture and sound from them, then adds in minimal keyboard elements and some editing to come-up with these distinctive unfolding sound washes. They go from the opening tracks, droning ornate and slightly sinister locked string melodies swamped in crackle, pops and hisses. To the stuck and dizzy brass fanfare loops of the track fanfares, which builds in growing and shifting ambient textures and appealing surface noise over the fanfares drifts and folds. On to the mysterious distant stuck flute sunrise of Shining, where Jeck slowly and carefully builds up the atmosphere adding smaller sonic details and sound loops and finally opens up into an heroic analogue synth-meets-guitar-like throb. I think that’s the other thing Sand seems to do differently from his other works I’ve heard; he keeps the tracks active, interesting and often sonically on the move.

With Sand, Jeck has made something very real, un-synthetic and often very emotionally pulling. I heartily recommend anyone interested in ambience, drone or hypnotic sound art to step into Jeck’s distinctive and rewarding soundworlds. [Roger Batty]

Uncut (UK):

A couple of weeks ago, I was writing here about the excellent new No Age album, and about indie orthodoxy masquerading as somehow adventurous in the world of shoegazing. Without going over the whole argument again, I think the gist was that early ‘90s shoegazing – which mainly sounds so bland now – acted as a gateway for me into a whole world of ambient, avant-garde music….

I was reminded of this last week by two things. One, the arrival of an album by a band called Sennen, which I must admit I haven’t heard, but the premise of someone naming themselves after a Ride song fills me, in 2008, with very little excitement. Two, the arrival of “Sand” by Philip Jeck, which is precisely the sort of expansive, challenging, ultimately aesthetically satisfying record that shoegazing inadvertently lead me to.

I have a few Jeck records, most recently his collaboration with the great Gavin Bryars on a new version of the latter’s “Sinking Of The Titanic” (LTM are releasing some Bryars work from the early ‘80s, incidentally, including some beautiful piano studies). Jeck is one of those avant-gardists who loiters awkwardly between the roles of musician and sound artist, seeing as he builds his music out of old records and record players.

He isn’t the first person to fetishise balls of fluff on old gramophone needles, of course: Portishead made a fortune out of distorting old hip hop breaks on their first album, after all. But for Jeck, the surface is the depth, so that “Sand” is a disorienting patchwork of static, churn and drift, out of which faint melodies – a familiar but unnameable orchestral vamp in the middle of “Chime Again”, for instance – sometimes emerge.

It’s hard to write about this sort of music without making it sound a bit forbidding, but – to use that shoegazing analogy – imagine the gauzy textures of My Bloody Valentine’s “To Here Knows When” reconstructed using radically different instruments, and moved even further away from the idea of a conventional tune.

The results are immersive and pretty revitalising, first thing on a Monday morning. I guess Jeck’s nearest reference point, even though he uses guitars rather than customised record players, would be his labelmate Christian Fennesz. Fennesz has a similarly voluptuous approach to noise, a taste for soiled ambience, and a gift for creating illusions of memory through his music. Jeck’s aged crackle, and the hints of half-unremembered tunes buried beneath it, create a kind of nostalgia for . . . what, exactly? Something nebulous, evanescent, a bit pretentious. Maybe for the days when, briefly, Slowdive sounded radical to me. . . [John Mulvey]

experimusic.com (Net):

Philip Jeck began exploring composition using record players and electronics in the early 1980’s. His most famous release came with ‘The Sinking of the Titanic’, an acclaimed collaboration with Gavin Bryars and Alter Ego. With ‘Sand’, Jeck makes a returns to the industrial textures that coloured his first release ‘Loopholes’, but fuses them with his symphonic grace and continued development as a composer and live performer. The seven tracks on ‘Sand’ move deep into the realms of organic dark ambience, similar in vein to Windy & Carl’s suffocating sheets of atmospheric drone but morphed within a sci-fi-esque ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’ aesthetic. Haunting textures of buzzing drone, harsh crackle and deep lucid bass bob ceremoniously like rippling waves in a bitterly cold Nordic bay, the elements joining forces in an attempt to hide the solace of semi-recognisable melodies that have become so frayed and distant.

Jeck works with old records and record players salvaged from junk shops turning them to his own purposes and playing them like musical instruments. ‘Sand’ was recorded live in Holland and England and edited using relatively rudimentary audio equipment which may contribute to the (intended) harshness of some of the prickly, treble heavy skree that exudes from the speakers. Occasional, scathing attacks of Merzbowian white noise will root listeners to their chairs whilst, in his quieter moments, shades of Thomas Brinkmann’s turntable experiments seep through. ‘Fanfares’ sounds like a sunken orchestra that gets caught up in a subversive loop, its frayed melodics hypnotically shimmering from beyond the droney sludge like shafts of light attempting in vain to penetrate the surface. ‘Shining’ takes on an eerie sub-aqua arabesque vibe, like the forgotten recordings by krautrocker’s ‘Agitation Free’ on their fact-finding tour of Egypt. Subtly expanding oud-like drones waft over hypnotically meandering and slowly intensifying frequency manipulations to make a sound like a silent but deadly dust cloud engulfing a once bustling, now baron terrain.

Proceedings start to become denser in the second half of the album with the manipulated vinyl sounds expanding in stature to create lusher sheets of trans-melodic drone closer in sound to Tangerine Dream or a depressed Terry Riley who only has access to the leftside of his organ. The bustling of ‘Fanfares Over’ recollects the dystopian aura of Blade Runner era Los Angeles with its mesmerising soundwave warps and percussive vinyl clicks that clamber progressively like an army of insects marching yonder. The whole thing then disappears into a short-lived static fuelled lull before a final onslaught of harsh blizzard-sonic’s formed by jostling shards of drone and static. The abrupt ending is so abrupt that the ensuing silence psychically hurts. With ‘Sand’ Jeck has crafted a surreal piece of progressive drone that swirls with hypnotic intent. (KS)

Sound of Music (Sweden):

Till en början blir jag lite konfunderad över britten Philip Jecks senaste alster “Sand”. Att hitta rätt ljud att loopa bland de gamla vinylskivorna han inhandlat på diverse loppisar är a och o för att hans koncept ska fungera, men lyckas han verkligen denna gången? På några låtar absolut, men ur ett helhetsperspektiv? Efter upprepade lyssningar tycker jag ändå det, även om inte allt är mästerligt.

Philip Jeck har varit Touch trogen i många år (om än några avsteg gjorts, bland annat med den fina duoskivan med Janek Schaefer på Asphodel). Framförallt har han spelat in solo, men också med konstellationen Spire och nu senast med Gavin Bryars och Alter Ego på skivan “The Sinking of the Titanic (1969-)”. Med skivspelare, vinylskivor, en casiosynt, en mixer och en inspelningsbar minidisc har han lett in skivspelarkonsten på helt nya spår. Ibland har originalinspelningarna dykt upp som byggbara loopar som gett Jecks skapelser melodier och tematik, men framförallt har de förvridits till något helt annat. Till loopade ljudlandskap som i sina skepnader kan variera kraftigt men som ändå alltid stavas J-e-c-k.

En av de saker som skiljer Jeck från andra som arbetar med samma form av stämningsskapande, filmiska och i tid utdragna musik är den ständigt hörbara loopen. Att looparna de facto skapas av skivor som snurrar på skivtallrik ger hans låtar en cirkulär form i ständig rörelse. Det går naturligtvis att skapa med en dator, men mig veterligen finns det ingen som gör det lika konsekvent som Jeck. Han återupprepar fragment likt bilder ur minnet. Att med hjälp av vinylskivor manipulera såväl det personliga som det kollektiva minnet är ju annars en specialgren för Jeck.

“Sand” är sju låtar inspelade live i Holland och England under 2006 och 2007. Det är inga väldiga förändringar som skett sedan det förra soloalbumet “7” kom för några år sedan. Snarare handlar det om förfining och fördjupning. Avslutande “Fanfares Over” byggs under 11 minuter upp till en fantastisk skapelse med inslag av både långa toner och fasta percussiva rytmer. Stundtals blir det nästan noise med vassa kanter. “Shining” är betydligt mer tillbakahållen. I bakgrunden upprepar en flöjt en primitiv melodi, i förgrunden snurrande miljöljud. Låter i ord inte så mycket för världen, men Philip Jeck lyckas göra det intressant, han fyller rummet med både stämning och mystik. [Magnus Olsson]

Gramophone (UK):

AVUI (Spain):

mapsadaisical (UK):

Philip Jeck’s latest album for Touch, Sand (alliteratively aligning itself with Seven, Soaked and Stoke), is even more explicit about its reflective nature than usual, coming as it does with a quote from Emily Dickinson’s poem “The Chariot” on the cover. Like the poem, the album feels like a heavy-hearted reminiscence on the course of a life, with its long-distant highs long worn away by the falling sands of time. The end result is almost unspeakably moving, and may well be Jeck’s masterpiece.

Like the aforementioned chariot, Sand proceeds at funeral cortege pace past the monuments that mark the most memorable moments of an existence. From between the crackles of “Unveiled” escape the sounds of fairgrounds and carefree days, which are all too soon swallowed up by the swelling sounds of the clocks in “Chime Again”. There are three “Fanfares” on Sand; the first comes next, its layers of brass gloriously heralding a blossoming. After this the album turns greyer and in on itself through the bleak “Shining” and the heavily decayed “Fanfares Forward” (a dense rush of barely-discernible shadows). By the time of “Residue“, the music is ineffably distant and elegiac, only half-remembered. “Fanfares Over” is a hellish afterlife, long, jarring and disorientating, becoming interred in an eternally locked groove headed, like the chariot itself, for eternity.

This is the second great recording Jeck has been involved with this year, after the new recording of Gavin Bryars’ “Sinking of the Titanic” which soaked up such praise a few months ago. This is an even better trip through (a) history, guided by the sure hands of a pioneer. Sand is truly unforgettable. Buy it now from the untouchable Touch.

Vice (UK):

Black (Germany):

Pitchfork (USA):

The title and sonic inspiration for this track, which serves as a centerpiece for Philip Jeck’s upcoming album Sand, is Aaron Copland’s ubiquitous “Fanfare for the Common Man”. Copland wrote the brassy piece during World War II and it was obviously composed to inspire; Emerson, Lake & Palmer, who intuitively understood the tug of the piece’s naked pomp, famously covered it in the 1970s. Jeck, whose working method involves mixing and processing old records via multiple turntables, usually live, takes fragments of the “Fanfare” and turns them inside out. The result retains the original’s sense of nostalgia, but instead of triumph and progress it coats those feelings in decay and loss. You can almost see civilizations crumbling as the piece progresses, as the notes are caught in ever tighter and more confined loops and the droney throb of noise rises up to bury the melody. Jeck’s genius here is to create a piece that evokes three or four distinct feelings simultaneously, a dazzling emotional patchwork that is both disorienting and completely addictive. [Mark Richardson]

Dusted (USA):

Sand is both a measure of and a metaphor for time, which is doubtless why Philip Jeck picked it as the title of his latest recording. Themes of memory, loss and perseverance in the face of obsolescence are central to his art, and the quote in the liner notes from Emily Dickinson’s “The Chariot” confirms that he hasn’t dropped the thread. It reads:

“…the Day

I first surmised the Horses’ Heads

Were toward Eternity.”

To rush through life, the poem seems to suggest, is to hurtle towards death. But Jeck’s own music rarely hurries. Instead “Unveiled,” Sand’s first track, creeps reluctantly into audibility. It sounds slowed down, as though someone had held their finger on the record. And maybe someone did; Jeck’s main instruments, after all, are beat-up second-hand records and portable turntables. He gives them a new lease on life, but at a cost. The gleaned fragments that he distorts and loops rarely sound whole. “Chime Again” is assembled from a looped, train-crossing bell and some muzak strings that have been filtered to a distant-horizon blur.

In general, Sand’s source material is less recognizable than ever, which makes the parts that you can make out (for example, the licks from Aaron Copeland’s “Fanfare For The Common Man” on three different tracks) seem especially significant on first listen. But, in short order, the anonymous elements overtake them, just as the music’s murky background swallows its foregrounded sounds. After a while, it’s the distant details, like the flute lurking at the edge of audibility on “Shining” or the high pitches scrambled by galloping horse hooves on “Fanfares Forward,” that register. They’re audio analogues to the forgotten life experiences that guide us from beyond the edge of consciousness. [Bill Meyer]

residentadvisor.net (UK):

Think of turntablism and the macho posturing of hip-hop types such as the Scratch Perverts spring to mind. Even experimental artists such as Q-Bert can never really escape the same testosterone template set down by Grandmaster Flash et al. But Philip Jeck is different. His interest in turntables begins where most people’s stop: at the last bit of the record and with vinyl which has been chucked in the bin.

What Jeck does is to turn the ends of records into engaging, multi-layered electronica. He samples and loops the sound of the needle hitting the runout groove, or where the record is scratched and keeps repeating. He also uses two record players from the early ‘60s (so they have 33, 45 and 78 and 16 settings) to play vinyl which comes from donation bins or rubbish heaps. An old Casio synth is the other accompaniment and the layers are filtered through a mixer and guitar pedal for effects.

Add to this Jeck’s touch and the 45 minutes of Sand end up rather like listening to someone tuning a radio whilst you’re semi-anaesthetised. Sounds drift in and out of your ear, and are subject to extensive echoing and delay, leaving you unsure of what they are. By my reckoning, there’s a plethora of chimes, chains jangling, ship funnels and WW2 news broadcasts, but you can’t be sure.

The seven songs lend themselves to mind-wandering and stretch your imagination to conjure whatever it wants, which makes Sand an immersive and engrossing listen. At the core of the tracks is the loop, but not in the sense of how it works in dance music. You can just about trace Jeck’s early interest in the percussive tracks of ‘70s New York DJs Walter Gibbons, Larry Levan and Shep Pettibone, but 30 years on Jeck’s loops expand, soar, and proclaim rather than simply propping up a vocal house diva.

Jeck waited three-and-a-half years between his last album 7 and Sand: the delay was because he felt dissatisfied with what he was producing. It was worth the wait. Sand is quite possibly his best work and definitely his most intense album to date. He reaches unprecedented levels of ferocity on the three tracks which make use of horns. ‘Fanfares Over’, in particular is enormously uplifting. I’ve never been inside a pan of water when it’s being slowly boiled, but I imagine that’s what the first half of the song sounds like. The second half morphs into what sounds like a loop of an aeroplane going overhead, which inflates further and further as fanning synths swarm that both disorientate and delight. By the end of the track I realised I spent the entire 11 minutes staring at a tree.

GoMag (Spain):

D-Side (France):

Almost Cool (USA):

By Jeck standards, Sand is fairly familiar in terms of overall construction and output. His work has been steady and sure for some time now, and despite a couple small ripples, it’s not like you’re doing to get dramatic changes from one album to the next. If anything, though, this newest effort might be a bit more dynamic overall, as it’s imbued with his usual sense of decay while also having a couple downright triumphant moments and some blasts of sheer noise. Both “Unveiled” and “Chime Again” start off in familiar territory, but it’s during the latter where some soft loops of orchestral swooning peak through the mist for just a moment, hinting at things to come.

Offsetting the remaining tracks on the release are three tracks that all use samples of Aaron Copeland’s “Fanfare For The Common Man,” and all of them have an understandable level of grandiose beauty that sounds just a slight bit more uplifting than one normally hears on a Jeck release (especially the slow-building “Fanfares Forward,” which clicks along with weird squeaks and scrabbles before plowing through a submerged, but still glorious finale. In other places, “Shining” and “Residue” are much more minimal, drifting with some soft humming drones and looping crackles of static that feel like giant come-downs after some of the other highs on the release. At this point in his discography (this is his fifth full-length for Touch), Sand is probably essential mainly for hardcore followers of his work, but like other artists working in such unique and specific ways, it does at least show some slight progression in sound, no matter how subtle.

failme.net (UK):

One of those artists I knew I’d like….good sounding surname, has nicely packaged albums out on the Touch label, uses vinyl. But somehow I’d never managed to immerse myself proper in any one of his long players. Whilst his back catalogue has always been there for instant consumption (from a career spanning 13 years), it’s nice to be presented with something ‘new’.

Carefully considered loops are run through that detuned radio effect that he seems to have patented. The source material consisting of filmic strings, bells, chimes and most effectively brass instrumentation sampled from Emerson Lake & Palmer’s ‘Fanfare For The Common Man’. It all sounds pleasant enough but the sudden shifts as frequencies pile up from the decay can jolt you. Low-end notes dissolve into weighty fuzz and speaker-troubling distortion whilst high end artefacts can cut through the recording with a burst of white noise.

The Observer (UK):

Jeck is known for conducting phantom orchestras of old record players. Liberated from the junk shop, his army of Fidelity phonographs generate a mighty static dust cloud, from which emerges a version of aaron Copland’s ‘Fanfare For The Common Man’ that knocks ELP’s into a cocked hat. [Ben Thompson]

Brainwashed (USA):

Run DMC once said that a DJ could be a band, or at least that’s how Chuck D paraphrased them. Dissecting that statement, it is perfectly logical to assume that a slab of vinyl could be an instrument, and this new disc from Philip Jeck proves that. Working live with record players, junk shop records, old Casio SK keyboards and recorders, Jeck has made a warm, nostalgic album that both personal and inviting.

Touch

For the most part, it is near impossible to tell that other people’s music was used in the creation of Sand. While far beyond the likes of simple sampling, Jeck did largely use prerecorded material as his raw sound sources, but the way he reshapes the sound into entirely new compositions is a testament to his talent and artistry. The swirling mass of clicks and pops that make up the basis of “Unveiled” could be simply run-out grooves amplified, or could be something else entirely. And, I doubt the chimes and symphonic loops that occasionally rear their melodic heads among the raw, rough moments sound completely different out of context than they originally did.

There are a few repeated elements throughout the disc, the chimes from the first track reappear in “Chimes Again” (imagine that), and horn fanfares are used in three tracks overall, “Fanfares,” “Fanfares Forward,” and “Fanfares Over.” The former two allow the horn bursts to be prominent in the mix alongside electronic squeals and harsher elements. “Fanfares Over” has the horn sounds completely trashed and cut up over top of machine gun tribal percussion and loops like swarms of killer bees overhead. Throughout its 11 minute duration the track stays dynamic, but also has some repeated segments that show a great attention to musical structure and elements that could easily be otherwise ignored in this context.

Most of the seven tracks on here feature that balance between abstraction and musicality, as well as an equilibrium between outright aggressive noise and careful, delicate melody. The aforementioned “Chime Again” features a lot of analog grime and distortion, but also beautiful, haunting melodies excised from the recordings and carefully presented as the calm within the storm. The soft crackles and buried tones of “Residue” become disarming with the quick transitions into jarring, harsher elements.

These gentle elements give a more inviting, personal character to Sand that is often lost in works such as these. The artwork, as always, by Jon Wozencroft, adds to this with its textural photographs that could be the wallpaper in an older family members home or something else that is warm and familiar, which is a perfect metaphor for this album.

Cokemachineglow (USA):

The fourth and most recent of Gavin Bryar’s attempts to record his minimalist classic The Sinking of the Titanic (1975, 1990, 1994, 2008) featured the help of Alter Ego and Philip Jeck; the project seems to have given Jeck some newfound inspiration. It’s hard not to hear echoes of Bryars or the analog tape loops of William Basinski in Jeck’s “Fanfares,” and trio of tracks interspersed throughout Sand, and perhaps the most “melodic” thing Jeck has done. The first part of “Fanfares” starts with a simple four-note motif by a small string ensemble that Jeck proceeds to layer in clouds of ambient dust and various acoustic samples, including the sound of galloping horses. Like Bryars or Basinski, Jeck has an excellent understanding of the emotional effect of decay and disintegration. For Basinski, The Disintegration Loops (2004) equated the natural decay of his decades-old analog tapes with the collapse of the Twin Towers; for Bryars, the The Sinking of the Titanic chronicled the true story of a string ensemble that insisted on playing while everyone else tried to escape with their lives. Though Sand doesn’t have an overarching concept like these records it similarly seems concerned with the way we emotionally perceive heavily-damaged source material.

There’s an obvious sense of decay and memory here, both in the way Jeck uses the bi-products of cracked vinyl but also in the sense that record-playing is still more physical than digital music. Thus he goes beyond most glitch artists—who likewise employ “mistakes” as the substance of their music—resulting in something that really feels like an artifact. Something stumbled upon. Interestingly, Sand is relatively stripped back in comparison to some of Jeck’s noisier records. On opener “Unveiled” the skipping of the record needle is all that maintains the rhythm, and it becomes more and more haunting as Jeck layers it with deeper aquatic pops and spurts. Creaking along at a zero-gravity pace, the track comes across like the perfect flip-side to Oval’s CD-scratch percussion which, even on their more ambient pieces, seems jittery and frantic.

Jeck works within the whole range of vinyl, from the physical movements of the record player to the actual samples themselves. The latter often sound ancient even when they’re relatively unmanipulated, like something from a dance song from the ’20s or ’30s. While the samples he uses give the tracks some melodic depth it often seems incidental; often they seem to just ride the crest of the continuous drone made of pops, echoes, and static. It’s an effect which goes a long way in proving just how finely-woven together these sounds are. Most of the time it’s impossible to parse the original material from its treatment: it sounds like there are original instruments behind the melodies in “Fanfares Forward,” but it’s nearly impossible to tell what exactly they are. Where they are discernible they rarely stick around for very long, like the xylophone that marks a sudden transition halfway through “Unveiled” but then quickly fades into the ether again. As the title suggests, Jeck seems more interested in continually uncovering minute details of the sounds; any recognizable instruments or melodies are simply transient.

Yet through all the seismic shifts that the tracks go through, there always seems to be a single, slow measured pulse. Call it the album’s beating heart if you will, but whether it’s distant galloping horses, the spinning record needle, the feint bells of “Chime Again,” or the octave leaps of “Fanfares Over” Sand‘s only constant is the passage of time. It’s hopeful, perhaps: like the string ensemble who kept playing while the Titanic sank, it’s a reminder of the presence of order in chaos. It’s also a reminder that, musically speaking, Jeck rarely sheds the discipline of drone or minimalist music like so many ambient artists who unwittingly lose themselves in an overabundance of gorgeous sounds. [Joel Elliott]

Laif (Turkey):

Bad Alchemy (Germany):

Uncut (Germany):

Goon (Germany):

plan b (UK):

Barcode (UK):

56-year-old Jeck is an English multimedia composer and choreographer, best known for his fascination with analogue sound sources and sample recording techniques – mostly taken from vinyl. Jeck, once a visual arts student, has been widely complimented on his theatre score productions in Europe, Japan and America.

Signed to the creditable Touch label, this new release sees Jeck in fine textural fetter. A seven track album, Sand delivers a series of intriguingly lengthy ethereal instrumentals here, all carrying a tangible sense of depth and aura.

Ambient, but not in the traditional sense, you can immediately tell that Jeck is a cut above the rest simply for his unique sense of spatial awareness, as swathes of almost industrial-sounding loops, sounds and samples compete for space, casting ever-changing shades of darkness and light upon what is a heavily-imprinted aural canvass.

Although Sand’s gritty analogue patina grates at times – its audio distortion, although deliberate, can be a harsh timbre to withstand – it doesn’t detract from the fact that the album is a bizarre goldmine of salvaged sound, capable of fascinating listeners who approach it with the appropriate subservience.

Squidsear (USA):

Philip Jeck immolates and ravishes his records. In giving them over to the turntable, one sort of inexorable procession tapers off and an unraveling of another kind begins to find its breath. Records, once kept at a distance, converge spontaneously, spiraling into an escalation of sound-events. It’s thus a music alluring in its shifting, snaking forms, telling in its evasiveness, memory, loss, and regeneration.

Sand seems an apt title in that it captures precisely this: pouring down, its pageantry of particles appear random and arbitrary in one sense, but in another way they burst with connection and share in a rapport of form. And so there are Jeck’s records: penetrated in every possible way, seething in every possible direction, arriving unexpectedly, but with initiatory form and guided metamorphosis.

Less gritty and abrasive in texture, and seemingly less strategic than past efforts such as Surf and Stoke, Sand is more of an enchantress. It’s quiet, but not still. To the contrary, it’s constantly moving, at times markedly abstract and ratiocinative, at times symphonic, pictorial, impressionistic even. Jeck seems to be examining his sound and its processes, but at the same time he spins a linear narrative. He is always coming back to his own subtly altered premises at the end of each episode, thus making each piece feel complete as a whole, and necessary in all of its parts. In this manner, from disparate source materials, he fashions personalized terms of texture and structural tension that are both lucid and mysterious.

Similarly, pieces are built upon conflicting but coinciding themes of spaciousness and confinement. Pieces open up onto a majestic vastness, its lines stretching off to an implied infinity, but always brushing up against a sort of ozone layer, which lends the proceedings a paradoxically closed feeling, leaving one with dense sound-fields. What perhaps most appeals is how every now and again, quite unexpectedly, very minor slippages or variable elements – some streams of piano or fluttering of flutes – peek through the fog or are simply exposed quite unwittingly. These are regal, finely shaped, arresting pieces, traversed with much of the grace and weakness of life on this sublunary plane. [Max Schaefer]

The Independent (UK):

Boston Phoenix (USA):

A recurrent theme of decay and loss haunts UK turntablist Philip Jeck’s music. The basic tools of his trade — thrift-store vinyl and vintage turntables often set at a tortoise-paced 16 rpm — are themselves haunted relics. As much medium as artist, Jeck coaxes warbling, spectral sounds from the worn grooves of his records. Half-familiar melodies are shrouded in a gauzy crackles and hums that mimic the soft temporal distortions of memory. On Sand, his seventh full-length on the lauded Touch label, the mood can be languid and melancholic, as on the hallucinogenic “Shining,” with its swirling flutes and trippy sitar(esque) motifs, or it can be gloriously exuberant, as during an exultant trio of fanfares. The last of these, “Fanfares Over,” spirals skyward in increasingly eccentric, quasi-drunken reverie, rising higher and higher until, without warning, it cuts to nothing. The sense of loss in the silence that follows is stunning. [Susanne Bolle]

Paperthinwalls (USA):

No one captures the inscrutable long-player epigraph quite like British turntablist Philip Jeck. The quote “Johnny Mathis advances the art of remembering” graced his 2004 effort 7, though it remains to be seen if there is a trace of Mathis in that album’s stylus fuzz and speaker murk. For his latest, Jeck elides all but the last lines of Emily Dickinson’s “The Chariot.” The implication of that carriage ride with Death and collapse of terrestrial time wherein “centuries; but each/Feels shorter than the day…” appears not on the surface, but only as one trolls deeper. “Fanfares” is but the first instance of Jeck kinking Aaron Copland’s “Fanfare For The Common Man,” which occurs thrice over the course of the album. Jeck sullies it each time anew, screwing down the pageantry so that it’s reduced to hobo slur, shellac crackle and titmouse squeak, making it sound like a warped reel of schoolhouse propaganda made quaint by the intervening decades and decline of Empire. Once regal, but now destitute and squalid, Jeck inverts his source so that it somehow resounds as something uncannily more grand and eloquent, precisely because of such decay, slowly riding us past the wreckage. [Andy Beta]

AAJIT (Italy):

Freistil (Germany):

Sonic Seducer (Germany):

Rumore (Italy):

Forest Gospel (UK):

For those familiar Philip Jeck, Sand shouldn’t come as any surprise. In addition to not being surprised, those familiar with Philip Jeck can also rest assured that Sand is incredible. For those unfamiliar, Jeck is an experimental turntablist, and no, I do not know exactly how he creates the bizarrely vibrant oddly enchanting soundscapes found on Sand and in previous releases. Last we heard from Jeck was his contribution to the utterly divine recording of The Sinking of the Titanic with Gavin Bryars and Alter Ego. On a release containing one track spanning past one hour, Jeck somehow made the sound of a crackling turntable sound euphoric preceding the oncoming swells of whale like beauty. On Sand Jeck has turned that same crackle and pop into something both beautiful and abrasive. The melodies here are rooted much deeper and are far more likely to turn dissonant than Alter Ego’s were. Yet, there are still ties to the general feeling of Sand and that of Bryars’s immutable classic. Sand is a seemingly dark affair, not in that it is inhabited by negative feelings or creatures of the underworld, but that its sounds feel like those that you might hear in an ominous, empty jungle at midnight. I guess in that way there is something terrifying interwoven within Sand, however in the course of the album there is something calming about the album – like the slow acceptance that you’re are going mad. A beautiful album for drifting away into nothingness, Jeck’s most recent release shows that he is the master of taming the off-kilter ambient circus. [Mr. Thistle]

allmusic.com (USA):

Released four years after Seven, Sand is Philip Jeck’s eighth solo album and a definite pick of the crop. While Seven had been a letdown from Stoke and the Vinyl Coda series, Sand rekindles the flame of the turntablist’s uncanny artistry. The format remains the same (seven tracks of short-to-mid duration), the modus operandi remains pretty much the same too (several record players, cheap keyboards, and now mini-disc recorders), but the results are a couple of notches above the bland Seven, moving back to the creative peak achieved with Stoke. Jeck is at his best when he is a sloppy droner, weaving textures but “dropping” them, letting suddenly harsh sounds cut through. Sand consists of seven separate pieces, but fanfare recordings appear in three of them, giving the album a sense of direction (“Fanfares” features an insistent snippet from Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man,” while “Fanfares Forward” and “Fanfares Over” push that element beyond recognition). “Chime Again” is a delicate piece based on church bells recordings. But the disc’s highlight is the opening “Unveiled,” a slow-developing piece in which turntables tell a number of parallel stories, strands of sounds transforming side by side, never quite crossing paths or being brought together, simply coexisting as simultaneous, complementary ideas. It seems that Jeck’s sound art will always be rougher around the edges than Janek Schaefer’s or Claus van Bebber’s — unfaded entries and exits, arbitrary end edits — but that is part of his unsettling power. Truth is, that’s also what made Seven too comfortable for its own good. [François Couture]

Losing Today (Italy):/

Foxydigitalis (USA):

“Sand” is the latest album by Philip Jeck, whose works are primarily made from old vinyl records and record players, as well as Casio keyboards and other junkshop equipment. While it’s uncertain exactly which records Jeck is using, they seem to mostly contain strings and horns (three track titles have “Fanfares” in the title), giving the album a sort of patriotic feel. Jeck’s collage methods are certainly different than other artists working with samples; most of his works seem to sample a few melodic fragments and loop them, adding distortion and other effects. A few times, he’ll throw in some sudden tape manipulations or bursts of noise. On the “Fanfares” pieces, he plays around with the pitch, creating some crazy warp effects. A couple of the pieces, such as “Shining”, take a little too long to develop and don’t really do anything exciting. At its best, however, “Sand” works in rescuing moments of beauty from obscure, forgotten elements. 7/10 [Paul Simpson]

Musica Reaction(France):

Les symphonies résiduelles de Philip Jeck

Philip Jeck aime les vieilles machines. Cet anglais initialement de formation visuelle (vidéaste et chorégraphe), collaborateur de l’acousticien Danois Jacob Kirkegaard, de Janek Schaefer ou du compositeur néo-classique post-minimaliste Gavin Bryars (entre autre), est aujourd’hui surtout connu pour ses ¦uvres électroacoustiques composées à partir de platines disques et de vinyles endommagés, de vieux synthétiseurs et de magnétophones antiques. Sa musique rugueuse évoque un lieu où le temps s’est arrêté. Une chambre vide dans laquelle un micro enregistrerait les bruits infimes de la poussière en mouvement. Un univers figé en apparence, mais paradoxalement habité de sons subliminaux, proche de l’ambient. Sur Sand, son dernier album paru sur le très pointu label britannique Touch, on peut noter une accumulation récurrente de dépôt sonore. Un dépôt luminescent, riche de minéraux, magnétique et hautement radioactif. On croit entendre des orages électriques qui grondent au loin, des vagues electrostatiques attirant les particules comme le sable qui s’envole sur une plage abandonnée. La tension latente qui vibre près des centrales électriques, le chuchotement des roues d’une automobile sur l’asphalte, le rugissement des avions dans le ciel. Or, rien de tout ça sur Sand, pas de captures live du son, pas de field recording, juste Philip Jeck, ses machines, un mixer Behringer, un synthétiseur Casio et un mini-disc Sony. Enregistré live, sur scène aux Pays-Bas et en Angleterre, Sand est une nouvelle expression du génie du britannique. [Maxence Grugier]

Barcode (UK):

56-year-old Jeck is an English multimedia composer and choreographer, best known for his fascination with analogue sound sources and sample recording techniques – mostly taken from vinyl. Jeck, once a visual arts student, has been widely complimented on his theatre score productions in Europe, Japan and America.

Signed to the creditable Touch label, this new release sees Jeck in fine textural fetter. A seven track album, Sand delivers a series of intriguingly lengthy ethereal instrumentals here, all carrying a tangible sense of depth and aura.

Ambient, but not in the traditional sense, you can immediately tell that Jeck is a cut above the rest simply for his unique sense of spatial awareness, as swathes of almost industrial-sounding loops, sounds and samples compete for space, casting ever-changing shades of darkness and light upon what is a heavily-imprinted aural canvass.

Although Sand’s gritty analogue patina grates at times – its audio distortion, although deliberate, can be a harsh timbre to withstand – it doesn’t detract from the fact that the album is a bizarre goldmine of salvaged sound, capable of fascinating listeners who approach it with the appropriate subservience.

Aural (Italy):

This album is dedicated to the passing of Phyllis May Jeck, and the notes resonate in an extremely sensitive way, inspired by a resigned quietness, yet at the same time molded from a strong inwardness. Even if they’re elegaic, the tones reflect the devotion to daily simplicity. Jeck, in his radical and contemporary music, succeeds to modulate the main topics of ancient art, and their preoccupation with mortality. In his work, contemporary and archaic categories are intertwined. The album finds itself in a new dimension, expressing a unique sound, which unravels over 7 different tracks. They are manipulations of personal and collective memories, developed in mechanical and industrial textures, blown with celebratory and symphonic arias. Jeck’s is a really touching work; and accomplishment and crowning of an excellent career, which has been fully orientated towards the definition of new musical criteria. [Aurelio Cianciotta]

Igloo (USA):

Turntablist Philip Jeck likes to boldly go beyond the vinyl frontier, though his music delights in the inbetween: in between sound art and music, aleatory and structured, pre-planned and indeterminate, abstraction and musicality, as well as between abrasive and non-pitch-specific tones and figures of melodic consonance. And interestingly, in terms of those generic epithets beloved of ambient reviewers, his pieces also malinger in between “dark” and “light,” being resolved towards neither (or perhaps both at once). And Sand’s pieces are also suspended between aperture and enclosure, outfolding towards the stars, while scudding against the ceiling and below stairs.

For those yet to check Jeck, he’s one of the few contemporary experimental sound artists directly descended from John Cage and Pierre Schaeffer, his turntablism steeped in a tradition with roots in early process-music experimentalism and musique concrète. This old sound-art collage kid turns base vinyl into something near to antique gold, sampling and looping needle-on-the-record surface noise, and itching his scratch perversion with two early ’60s record players with variable speeds, and nothing else but an old synth, a mixer and a guitar FX-pedal.

So, wrought almost entirely from scuffed and wrangled wax, the grain of Sand goes against you, but you find your ears going with it. The house that Jeck built is a haunted one of eerie remote presences, with sounds seeping up from a churning undertow of static and lo-fi drone before being effaced. The album starts out in the woozy click’n’pop soup of “Unveiled,” then moves on to “Chime Again,” which allows beautiful chiming timbres to stand proud of a base of plastic fantastic sampledelia. Three of the remaining tracks make diverse play with a fragment of Copeland’s “Fanfare For The Common Man.” The first, “Fanfare,” spools it out into wonky 70s TV intermission ambiance, allowing it to cling on to a grandiose faded beauty while buffeting it about. The second, “Fanfares Forward,” smears it into a grimy veil of mounting recursive progressions whose loopy gauze and queasy memory capture has something of the feel of another (albeit quite differently re-contextualizing) musico-culture vulture, Wolfgang Voigt. In the spaces in between, “Shining” and “Residue” lie low in repose, before finale “Fanfares Over” comes alive again to decompose Copeland and scatter his musical ashes over a slurry of loops run through what sounds like a massive antique flanger. The whole has a feel of the hit-and-miss about it, but what’s striking is how often and how powerfully it hits.

In closing, a reflection on the album’s title, which could secrete the germs of a meaning to the music’s methodical madness. Sand: perhaps an allusion to the particulate nature of its sound, but, equally, the properties of sand lead to associations with themes of time and/or impermanence, especially in combination with the discreet ellipses (…) appearing on the sleeve, and the accompanying fragment from Emily Dickinson’s The Chariot (better known to some as “Because I could not stop for Death…”) – a reflection on Time and Eternity. Like Bryars (The Sinking of the Titanic) or Basinski (The Disintegration Loops), Jeck understands the emotive heft of the sound of the decorous in decay. And though Sand doesn’t have a ready-made programme to patch itself into, it seems similarly disposed to explore the semiotics of damaged and/or aged sources, as it pushes ever further in its ethnography of evanescence into a multi-layered polytimbral in-between. One to Jeck. [Alan Lockett]

Rock & Pop (Czechia):

Rock A Rolla (UK):

Rockdelux (Spain):

Gonzo Circus (Belgium):

Bant (Turkey):

Orkus (Germany):

Pop Matters (USA):

Philip Jeck is mostly known for his methods, not his music, which is a damn shame. Long after you’ve forgotten or filed away the fact that Sand, like all of his albums, is composed and played purely on turntables, old found vinyl and record players, you’ll be struck by the way Jeck’s standard miasma of sound (quasi-industrial clanking, foggy orchestral melodies, the kind of staticky walls that Fennesz for one clearly took cues from) can be so instantly and powerfully moving.

Sand is dedicated to Jeck’s mother Phyllis, who passed away this year, and it skillfully avoids the kind of lumpen sentimentality that such a dedication would normally entail. The track titles—“Shining”, Chime Again”, and the trio “Fanfares”, “Fanfares Forward” and the closing “Fanfares Over”, suggest tribute in terms of glorification rather than sadness, and the ringing, bright opening of “Fanfares Over” especially manages to be both melancholy and joyful, and moving in a way most valedictory music never touches.

Admittedly Jeck’s music never really changes, although he manages to get a lot of variation out of a fairly narrow set of sounds, but Sand also doesn’t break the trend of consistently high quality that Jeck’s had going for years now. The context alone might get a few more people to check out his otherworldly, dense form of turntablism, but fans will find more of the wonderful same.

Touching Extremes (Italy):

The art of suggestion via the manipulation of old vinyl records was not born yesterday, and there is not much that a performer can do to add or subtract meanings to objects that seem to exist exactly for the purpose of fixing an era in some sort of artificial mental environment that only our own personality will determine. Together with Janek Schaefer (my personal favourite in this field, I must admit), Philip Jeck has been active for many years now trying to convey the spirits of a past that might still be useful as far as introspection and self-analysis are concerned. “Sand” is a selection of live recordings from Holland and England (2006-7) which the composer re-edited in a consistent whole this year. During the concerts, Jeck utilized Fidelity record players, Casio SK keyboards, a Behringer mixer and a Sony minidisc. As it usually happens with this kind of composition, repetition and blurred edges are the main constituents of a series of trance-inducing soundscapes whose complexion is spoiled by the scars of distortion and crackle, which the author exploits as one of the numerous shades to maintain the half-nostalgic, half-scary area that this music generates. Heavenliness is not allowed: we’re talking about the short-lived sensations that one experiences while wandering through the “zone”, that jumble of incomprehensible joy of existing and fear of the future, the unrecognized fuel allowing the so-called sentient beings to go on in their clueless quest towards a non-existent completion, an afterwards where the “after” is missing. [Massimo Ricci]

de:bug (Germany):

Vanguardia (Spain):

Blow Up (Italy):

The Sound Projector (UK):

TheVibes.net (Italy):

E’ purtroppo arrivato un po’ in ritardo rispetto alla data di pubblicazione questo nuovo lavoro dell’abile compositore e coreografo inglese Philip Jeck, ma vogliamo comunque segnalarvelo in previsione dell’imminente esibizione – prevista per il 6 marzo prossimo venturo – all’interno del Fosfeni festival in qual di Cascina nella provincia di Pisa. Numerosi lo ricordano per l’esibizione Vinyl Requiem che meritò un riconoscimento da parte della blasonata rivista Time Out nel 1993, non fosse altro per la curiosa line up che tutto farebbe pensare tranne che a un requiem vinilico, visto che durante quella performance Mr.Jeck performava con ben 180 Dansette, gloriosi modelli di giradischi lanciati dall’imprenditore russo Morris Margolin sul mercato inglese e che negli anni 60 impazzavano tra gli adolescenti tanto che potrebbe instaurarsi un paragone con idolatrati oggetti dei desideri dei giovani musicofili contemporanei come l’iPod. La particolarità di Jeck nelle sperimentazioni che seguirono potrebbe riassumersi in ciò che è stato già detto sul suo modus operandi: il suo interesse per le miscelazioni comincia laddove quelllo altrui finisce, visto che sebbene operi plasticamente sui decks come il più classico dei “turntablisti” ciò che miscela e “scratcha” non sono beats ma frequenze e il suo lavoro è molto più simile a quello di un pasticciere chiamato a fare una torta strato su strato che gradualmente debba raggiungere l’altezza di un’immaginaria Torre di Babele. Potrebbe definirsi turnlayerism questa sua attitudine di stratificare frequenze talvolta prossime al silenzio in cui vi innesta di tanto in tanto suoni presi da un vecchio sintetizzatore Casio e vi interpone i filtri di qualche pedaliera per chitarre. I tre quarti d’ora di Sand sono quanto di più immersivo potreste aspettarvi da siffatto campionario strumentale: onde che vengono frastagliate da delay clausurali e ripetuti con lievi echo, tintinni rarefatti di carillon, un double dubbing infinito che sembra applicato alle registrazioni su cassetta di radiofrequenze di stazioni inesistenti, loops che giungono al momento in cui ricominciano in tempi molto allungati. Ed è proprio il tempo e il terrore dell’oblio appaiono essere la colonna concettuale portante dell'”arte” cesellatrice del signor Jeck, che tanto per aggiungere un’alea intellettualoide (come comunemente si conviene in questo genere di lavori apparentemente astratti e astrusi) cita la Dickinson più esegetico quando estrapola da The Chariot al fine di dare un inquadramento memetico all’ascolto le seguenti abbacinanti parole: “the Day/I first surmised the Horses’ Heads/Were toward Eternity”.

Al di là della congettura sulle teste equine proclive all’eternità (immagine innegabilmente suggestiva…) che accomunerebbe il sonomanipolatore Philip alla poetessa Emily, si potrebbe dire che il primo gioca con l’enarmonia come la seconda con l’enclisi soprattutto in questo Sand – frutto di registrazioni estemporanee che hanno avuto come contesto imprecisati studioli in Inghilterra e in Olanda tra il 2006 e il 2007 e riassemblati a Liverpool all’inizio dell’anno appena passato -. Sebbene le sorgenti sonore sono inevitabilmente prese da altri lavori – visto che oltre ad usare piatti di generazioni oramai remote, Philip prende per il suo modo di fare “sampling” vecchi vinili anche malconci -, il processo compostivo le rende inevitabilmente autoreferenziate: qualcuno per esempio scorge echi di musiche usate per sonorizzare i vecchi filmati della seconda guerra mondiale nelle tre fanfare – presenza che va in parte ricollegata alla dimensione personale dell’album, dedicato a Phyllis May Jeck, padre dell’autore scomparso lo scorso anno -, capolavori di sgretolamento sonoro in cui le “vittime” designate della dematerializzazione digitali sono come nelle fanfare che si rispettano dei corni. Ma di fatto provare a cercare delle similutidini è una perdita di tempo evitabile. Meglio farsi assorbire dal suono fino al procelloso bombardamento uditivo degli undici minuti di Fanfares Over, in cui i suoni riemersi dalla memoria del compositore sembrano gradualmente svanire divenendo irriconoscibili nella tempesta (di sabbia?) dell’oblio. Viaggio acusmatico godibile e coinvolgente al punto che alla fine della riproduzione, potreste meravigliarvi nel constatare che il vostro sguardo è rimasto imbambolato su un punto imprecisato dello spazio circostante, staticità che potrebbe divertitamente contrastare con l’accelerazione ai pensieri impressa dal sound avvolgente dall’abilissimo Philip. Del resto in questo consiste il fascino e la bravura di questo riconosciuto “spalmatore” di frequenze. Straconsigliato. [Vito Camarretta]

R&V (Greece):